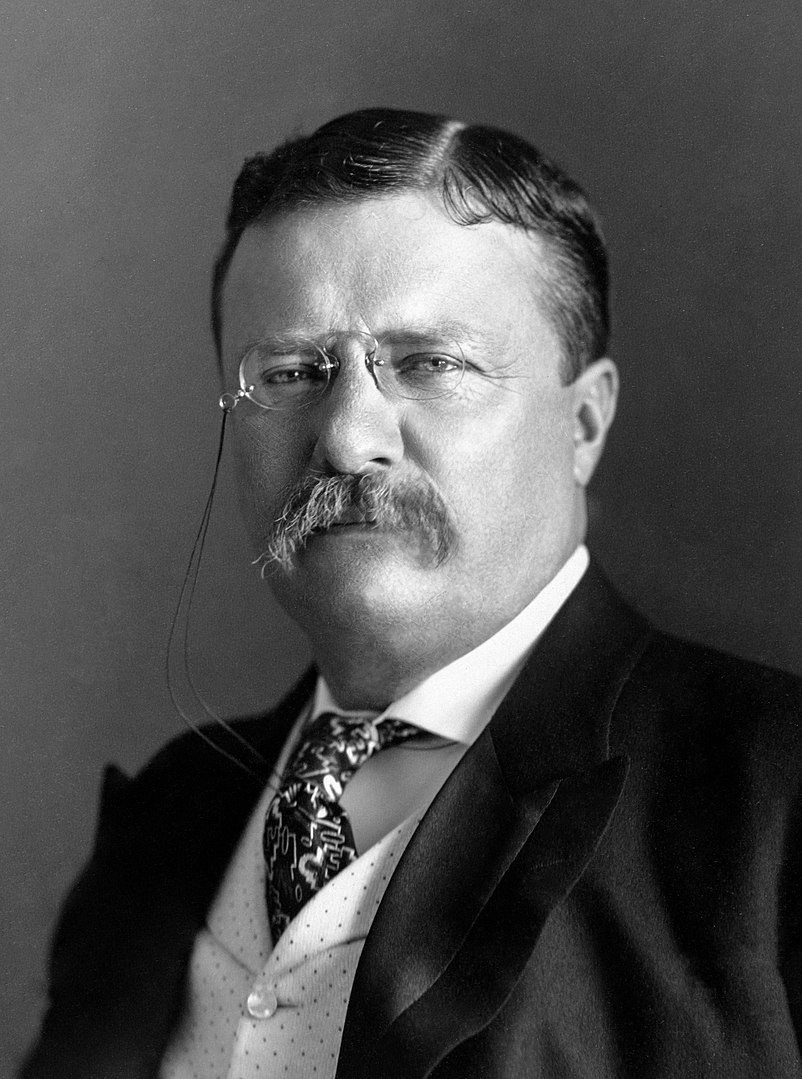

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was born to a wealthy family in New York. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Harvard and studied law at Columbia, but he never embraced legal technicalities and spent most of his life in politics.

He was elected to the New York Assembly, was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as a commissioner of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, became president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners, was appointed by President William McKinley as an assistant secretary of the Navy, resigned to lead a group of “Rough Riders” who fought in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, and was elected governor of New York.

President McKinley, whose first running mate Garret Hobart died in 1899, chose Roosevelt as his running mate in his reelection campaign in 1900.

In September of 1901, Roosevelt became president upon McKinley’s death from an assassin’s bullet. At 42, Roosevelt was and remains the youngest man ever to hold this office. After serving two terms, Roosevelt supported William Howard Taft in the 1908 election. Roosevelt later ran unsuccessfully for president in the 1912 election in which Woodrow Wilson was elected.

Roosevelt was a sickly child who sought to overcome his health problems by engaging in a strenuous lifestyle, which would, in time, include African safaris and a trip down the Amazon River. After his wife and mother died, Roosevelt spent time on a cattle ranch in the West where he further developed a love for the outdoors that would later lead to his conservation efforts.

Roosevelt was the first president to be routinely known by his initials (TR), or as Teddy. The teddy bear was named for him after he spared the life of a stray cub that wandered into his camp during a hunting trip in Mississippi.

Roosevelt pushed strong foreign policy, arranged for Panama Canal

Generally embracing progressive policies, which he called the “Square Deal,” Roosevelt was a larger-than-life figure (he is one of four presidents whose image is carved into Mt. Rushmore) and a powerful orator who continued giving a speech during his 1912 electoral bid after being shot by a would-be assassin.

He often referred to the presidency as providing a “bully [good] pulpit” for persuading the public. Roosevelt worked for anti-trust laws and other consumer protections.

Roosevelt was incensed by the Supreme Court decision in Lochner v. New York (1905), in which the court struck down state regulation of bakers' hours on the basis that it violated contract rights of bakers (the idea of “substantive due process”). Roosevelt was among those who favored reforms to make the court more responsive to public opinion.

An advocate of a strong foreign policy, Roosevelt sent American warships (the Great White Fleet) on a worldwide tour and arranged for the construction of the Panama Canal to link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He became known for the adage, “Speak softly and carry a big stick.”

An advocate for entering World War I earlier than the nation did, Roosevelt requested to lead a brigade when the U.S. eventually joined the conflict but he was turned down by President Wilson (Bader 2016, 312).

Roosevelt supported religious freedom, separation of church, state

Roosevelt has been described as “a moralizer and preacher;” as “an ecumenist” who accepted Catholics and Jews; as “a champion of the separation of church and state; and as “a religious pilgrim” (Wetzel 2021, vii). In 1906, Roosevelt became the first U.S. president to appoint a Jew, Oscar Straus, to a cabinet post when he named him as his secretary of commerce and labor.

As president, Roosevelt supported Utah Senator Reed Smoot, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, against efforts by the Senate to expel him from that body on the basis of his religious affiliation (Wetzel 2021).

Although Roosevelt had supported the decision by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to remove the words “In God We Trust” from some coins he had been asked to design, Congress overruled this decision and Roosevelt read the political winds to know not to veto the law (Wetzel 2021, 100-102).

Roosevelt opposed Bible reading in religious non-homogenous public schools where authorities would have to decide which version to choose (Wetzel 2001, 182).

First campaign finance regulations passed during Roosevelt’s term

After Duke University refused to fire Professor John Bassell for expressing the view that Booker T. Washington, whom Roosevelt had hosted at the White House, was the greatest Southerner other than Robert E. Lee, Roosevelt took a train to visit and commend the decision: “You stand for Academic Freedom, for the right of private judgment, for a duty more incumbent upon the scholar than upon any other man, to tell the truth as he sees it, to claim for himself and to give to others the largest liberty in seeking after the truth” (Kovarik 2022).

The first federal law regulating campaign finance, the Tillman Act of 1907, was adopted during Roosevelt’s administration, banning some corporate contributions to federal elections.

In United States ex rel. Turner v. Williams (1904), the Supreme Court upheld the deportation of an immigrant anarchist over arguments made by Clarence Darrow that his views were statements of abstract belief rather than calls for overthrowing the government.

Roosevelt pens essay on Lincoln and free speech

Roosevelt had advocated American entry into World War I long before President Wilson had called for it, and as the war was coming to an end, he feared that Wilson would stress peace over victory. In May of 1918, Roosevelt penned an essay on “Lincoln and Free Speech,” which appeared in the Metropolitan Magazine.

In his opening paragraph, Roosevelt said that “Patriotism means to stand by the country. It does not mean to stand by the President or any other public official save exactly to the degree in which he himself stands by the country. It is patriotic to support him in so far as he efficiently serves the country. It is unpatriotic not to oppose him to the exact extent that by inefficiency or otherwise he fails in his duty to stand by the country.”

Roosevelt further observed that:

The authors of the first amendment to the Federal Constitution guaranteeing the right of assembly and of freedom of speech and of the press did not thus safeguard those rights for the sake alone of persons who were to enjoy them, but even more because they knew that the Republic which they were founding could not be worked on any other basis. Since Marshall tried Burr for treason it has been clear that the crime cannot be committed by words, unless one acts as a spy, or gives advice to the enemy of military or naval operations. It cannot be committed by statements reflecting upon officers of measures of government.

Defining sedition as meaning “to betray the government, to give aid and comfort to the enemy; or to counsel resistance to the laws or to measures of government having the force of law,” Roosevelt distinguished such illegal actions from criticism of government officials or their actions. He thus noted that although “Any one who directly advises or counsels resistance to measures of government is guilty of sedition,” this “ought to be clearly distinguished from discussion of the wisdom or folly of measures of government, or the honesty or competency of public officers.” He used Abraham Lincoln’s opposition to President James Polk’s policies in the Mexican-American War as an example.

Arguing that “The administration’s warfare against German spies and American traitors has been feeble,” Roosevelt observed:

“We will stand behind the country at every point, and we will at every point either support or oppose the administration precisely in proportion as it does or does not with efficiency and single-minded devotion serve the country.”

Roosevelt cultivated the press, creating room in White House

Roosevelt was president at a time when the U.S. Supreme Court had not yet applied provisions of the First Amendment to the states. In its first free press case, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Patterson v. Colorado (1907) that it could not review a state contempt conviction of a newspaper for criticizing the state supreme court. The decision, authored by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., rested in part on the understanding that freedom of the press was chiefly designed to prevent prior restraint of publication rather than any future punishments.

Recognizing the increasing importance of reporters, Roosevelt was more accessible to the press than any of his predecessors, and he did much to cultivate its members. He was the first president to create a room for the press on the first floor of the White House and later designated a room in the newly created west wing where the press could call in their stories rather than having to send them by couriers (Jeurgens 1982, 119).

Roosevelt pursued unsuccessful libel lawsuit against Joseph Pulitzer

Roosevelt was sensitive to press criticism and pursued libel suits against newspapers that raised questions of financial graft related to the Panama Canal. In 1909 in United States v. Smith (Ind.) a case in which Roosevelt tried to prosecute the Indianapolis News for stories questioning the financial aspects of the U.S.'s purchase of the canal, a federal district court ruled that libel prosecutions within states had to be limited to libels that had occurred there. Roosevelt also sought federal libel prosecutions against Joseph Pulitzer and other newspaper editors who alleged he profited from the sale of the Panama Canal. But in United States v. Press Publishing Co. (1911), the U.S. Supreme Court decided that there was no federal crime of libel.

In 1914, Roosevelt prevailed in a libel suit that had been brought by a New York Republican leader whom he had accused of corruption (Wetzel 2021, 182-183).

Roosevelt appoints Oliver Wendell Holmes to Supreme Court

Roosevelt appointed three justices to the court. They were Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Rufus Day, and William Moody. Holmes became a particularly influential justice on matters related to freedoms of speech and press.

Although they were not personal friends, Woodrow Wilson, and later Franklin D. Roosevelt, a fifth cousin whose wife, Eleanor, was Teddy Roosevelt’s niece, exercised similarly expansive powers when they were chief executives.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 21, 2023.