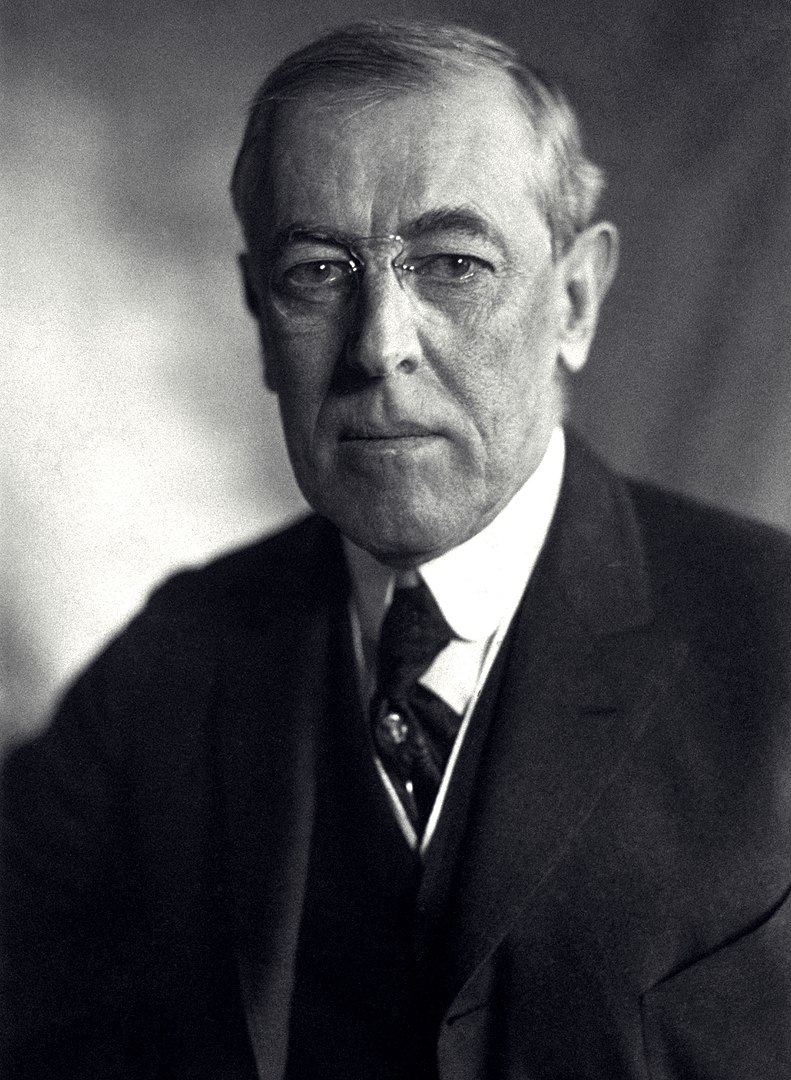

Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was one of the more consequential presidents of the 20th century, serving as president from 1913 to 1921, a period that included World War I.

Born in Virginia to the family of a Presbyterian minister and raised in the South, Wilson earned his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University, briefly practiced law in Georgia, and then earned his Ph.D. in history and political science from Johns Hopkins University.

Wilson taught at Bryn Mawr and at Wesleyan University before taking a job at Princeton. He was a prolific writer who deeply admired the English parliamentary system of government; in time, he became an advocate of an activist presidency. After becoming president of Princeton, Wilson served as governor of New Jersey. He won the presidency in 1912 as the Democratic candidate after a contest against sitting president William Howard Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt, who, as a Progressive (Bull-Moose) candidate, split Republican voters.

Wilson’s second term marked by entry into WWI

Wilson, the U.S.'s 28th president, embraced a number of the progressive policies of Theodore Roosevelt. In presenting proposals for tariff reform, he appeared before a joint session of Congress. He also resumed the practice that Thomas Jefferson had discontinued of presenting the annual State of the Union Address in person.

In the same year that he became president, the 16th Amendment had granted Congress power to adopt a national income tax, and the 17th Amendment provided for the direct election of U.S. senators, replacing the process in which they were selected by state legislators. In 1917, the nation adopted the 18th Amendment, which provided for national alcoholic prohibition.

Congress adopted a number of Wilson’s proposed economic reforms. These included: lowered tariffs; the adoption of the Federal Reserve Act, which created the Federal Reserve System with 12 regional reserve banks; the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission; and the Clayton Antitrust Act. The Panama Canal, which Teddy Roosevelt had initiated, was opened in 1914.

Wilson was reelected in 1916 in a contest with Charles Evans Hughes, who resigned a seat on the Supreme Court to run and who would later return to serve as chief justice. Wilson’s reelection was due in part because he had successfully kept the United States out of World War I.

In his second term, however, the U.S. entered the war after Germany resumed submarine warfare. Wilson described the conflict both as “a war to end all wars” and as a war “to make the world safe for democracy.” He later pushed for the League of Nations. Because the U.S. had not been directly attacked, there was a fair amount of opposition and concern about the loyalty of German Americans. The popular mood was further inflamed when communists took over Russia.

Wilson pushed for restrictions on speech as wartime measures

Wilson pushed for the enactment of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, and the Supreme Court of the day accepted restrictions on freedom of speech and press as necessary wartime measures. Although Wilson somewhat reluctantly advocated the 19th Amendment, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex, he allowed for the imposition of racial segregation in governmental agencies.

America’s victory in World War I was followed by a devastating influenza epidemic. Wilson met with Allied leaders at the end of the war, advancing “14 Points” outlining his vision for the post-war world. But after barnstorming across the United States advocating for U.S. participation in the League of Nations, Wilson had a stroke. He left the presidency as a broken man, and Warren G. Harding was elected on a promise to return to “normalcy.”

Espionage and sedition laws led to convictions of anti-war activists

Despite Wilson’s reputation for progressivism, the legacy of the Wilson Administration with respect to free speech is largely one of repression. Shortly after U.S. entry into World War I, Congress, at Wilson’s urging, adopted the Espionage Act of 1917. A scholar notes that the law made it a crime “to convey false information in order to interfere with the American military or promote the success of America’s enemies,” “to cause or attempt to cause insubordination within the military,” or “to willfully obstruct military recruitment of enlistment.”

In the even more restrictive Sedition Act of 1918, Congress further restricted “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the United States.

Palmer raids during Wilson’s presidency led to mass arrests

In 1917, Wilson created a Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, which used propaganda to muster support for the war. Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, led a series of raids on communist and socialist organizations that were considered to be radical.

Palmer’s mass arrests, in addition to undermining First Amendment and other rights, further stoked fears that led to the first Red Scare. In a later victory, in Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), the Supreme Court struck down a state law adopted during this period that had forbidden the teaching of German in schools.

The Supreme Court had yet to declare in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that the free speech and press provisions of the First Amendment applied to the states, and its decisions with respect to federal laws were far from liberal.

Supreme Court upholds Espionage Act convictions during Wilson’s presidency

In Schenck v. United States (1919), Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., articulated the “clear and present danger test” to uphold a conviction under the Espionage Act of individuals who had circulated materials likening the draft to involuntary servitude.

Later that year, Holmes and Louis Brandeis dissented from the opinion in Abrams v. United States in which the court upheld the conviction of another set of individuals who had issued leaflets condemning U.S. military intervention in Russia. That same year, in Frohwerk v. United States and Debs v. United States, the court upheld the conviction of individuals who had criticized U.S. participation in World War I.

In Schaefer v. United States (1920), the court, with Holmes and Brandeis in dissent, further upheld the conviction of German American publishers for changes they had made to articles dealing with the war.

In part in reaction to Wilson’s policies, the National Civil Liberties Bureau was founded in 1917 and became the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920. This organization continues to defend individuals whose First Amendment rights have been violated.

Wilson believed religion should be in public sphere

A Wilson biographer, Brian Morton, has observed that Wilson tended “to conflate spirituality with nationalism.” In a speech on May 7, 1911, on the Tercentenary Anniversary of the King James Bible, Wilson proclaimed that “America was born a Christian nation. American was born to exemplify that devotion to the elements of righteousness, which are derived from the revelations of Holy Scripture.” Wilson, who was a part of the social Christianity, or social gospel, movement, believed that Christians had an obligation to bring their faith into the public sphere and often brought his own moralism to political issues.

Wilson appoints Brandeis, McReynolds, Clarke to Supreme Court

Wilson appointed three Supreme Court justices: James McReynolds, Louis Brandeis and John Clarke.

Although he authored the decision in Pierce v. Society of Sisters upholding the rights of parents to send children to parochial schools (1925), McReynolds was generally regarded as a reactionary on the court, while John Clarke, who wrote the majority opinion in Abrams v. United States, resigned after six years to advocate for U.S. participation in the League of Nations.

Justice Brandeis, the first Jew to be appointed to the Court, was a strong defender of First Amendment rights and often joined in opinions with Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Wilson was succeeded in office by Republican Warren G. Harding, who promised a return to “normalcy.” In 1921, he commuted the remaining sentence of Eugene Debs.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 22, 2023.