William Howard Taft (1857–1930), a lawyer, jurist and politician, is the only person to have served as both president and then as Supreme Court chief justice of the United States. As chief justice, from 1921 until he retired in 1930, Taft presided over the Supreme Court as it began to incorporate First Amendment provisions into the due process clause of the 14th Amendment.

Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of Alphonso Taft, a prominent Republican lawyer and judge who served as secretary of war under President Ulysses S. Grant. William Howard Taft followed in his father’s footsteps, attending Yale and later serving as secretary of war. He earned a law degree in 1880 from Cincinnati Law School.

His career began with his appointment as assistant prosecutor of Hamilton County in Ohio. Within two years, in 1882, he was appointed local collector of internal revenue. Five years later he was appointed judge in the Ohio Superior Court, where he sat until 1890, when President Benjamin Harrison appointed him solicitor general of the United States. In 1892 Harrison made him an associate judge for the newly created U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. Taft became chief judge and held the post within the 6th Circuit until 1900, after which President William McKinley appointed him as governor of the Philippines. During this time he earned a doctor of law degree from Yale Law School. In 1904 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him secretary of war, sending him to Japan and Cuba. Taft also helped oversee the beginning of construction on the Panama Canal.

President William Howard Taft is seen throwing out the first ball of a baseball game for the Washington Senators in Washington in 1912. In 1921, upon the death of Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, President Warren G. Harding nominated Taft to be chief justice. He was unanimously confirmed by the Senate. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Taft won the 1908 presidential election

Theodore Roosevelt began to plan for Taft to succeed him as the Republican presidential candidate in the 1908 election. Although Taft himself would have preferred an appointment as chief justice, he ran for and won the presidency. As president, Taft differed greatly in style from his predecessor and mentor; most significantly, he believed in working within the confines of law instead of stretching presidential powers as Roosevelt had done.

Taft helped establish a parcel post system, expanded the civil service, and strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission. He signed a law that created the Department of Labor. He also supported passage of the 16th Amendment, which permitted a national income tax, and the 17th Amendment, which mandated the direct election of senators by the people. In foreign affairs, he pursued what he termed “dollar diplomacy” to further economic development of less-developed nations.

During his presidency, Congress adopted the Wireless Ship Act of 1910 and the Radio Act of 1912, both of which regulated radio communications. In 1912, in Gandia v. Pettingill, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a libel conviction and set the stage for future rulings on the subject.

Taft alienated many liberal Republicans — including eventually Theodore Roosevelt himself. These Republicans formed the Progressive Party, which split Republican votes in the election of 1912 and resulted in the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson. After his defeat, Taft went on to serve as Kent Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale Law School and as president of the American Bar Association.

As president, Taft appointed six different individuals to the U.S. Supreme Court. There were Horace H. Lurton, Charles Evans Hughes (who would later succeed Taft as Chief Justice), Edward D. White (whom he appointed as Chief Justice), Willis Van Devanter, Joseph R. Lamar, and Mahlon Pitney.

Taft vetoed a law in 1911 admitting New Mexico and Arizona as states because he disfavored provisions in their constitutions that would have allowed for the recall of judges.

Taft was nominated to the Supreme Court after his presidency

In 1921, upon the death of Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, President Warren G. Harding nominated Taft to be chief justice. He was unanimously confirmed by the Senate. As chief justice, Taft wrote more than 200 opinions for the high court, utilizing a strict constructivist approach to constitutional interpretation that was historically and contextually based. He used his political clout to urge Congress to pass the Judiciary Act of 1925, which increased the court’s authority over its certiorari jurisdiction.

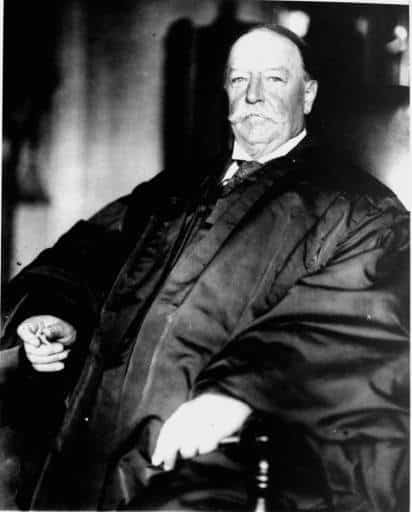

Chief Justice William Howard Taft in 1930. As chief justice, Taft wrote more than 200 opinions for the court, utilizing a strict constructivist approach to constitutional interpretation that was historically and contextually based. The Taft Court decided that First Amendment protections extended to states as well as to the federal government. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Taft Court examined whether the First Amendment applied to the states

The Taft Court examined the question of whether the First Amendment extended to states as well as to the federal government.

In Gitlow v. New York (1925), Justice Edward Terry Sanford ruled for the court that the First Amendment applied to the states: “For present purposes we may and do assume that freedom of speech and of the press — which are protected by the First Amendment from abridgment by Congress — are among the fundamental personal rights and ‘liberties’ protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from impairment by the States.” The decision served as the benchmark for future decisions that struck down state laws that violated rights protected under the First Amendment.

Later cases, such as Fiske v. Kansas (1927), which invalidated a state syndicalism law, solidified that position and upheld the incorporation doctrine undertaken in Gitlow. The incorporation doctrine holds that selected provisions of the Bill of Rights are applicable to the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment.

In 1926, Taft authored the consequential decision in Myers v. United States that allowed a president to fire a postmaster who had been confirmed with the advice and consent of the Senate. Taft also successfully lobbied Congress for the current building designed by architect Cass Gilbert that houses the Supreme Court, although he did not live to see it completed. He died a little over a month after his retirement from the court in 1930.

Taft’s son, Robert Alphonso Taft later went on to serve as an influential Republican U.S. senator from Ohio from 1939-1953.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2024 by John R. Vile, the dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Dale Mineshima-Lowe is Managing Editor for the Center of International Relations, researcher and Associate Lecturer in both the Department of Politics and Department of Geography at Birkbeck, University of London, and Tutor of Politics and History at the City Lit, adult education college in Central London.