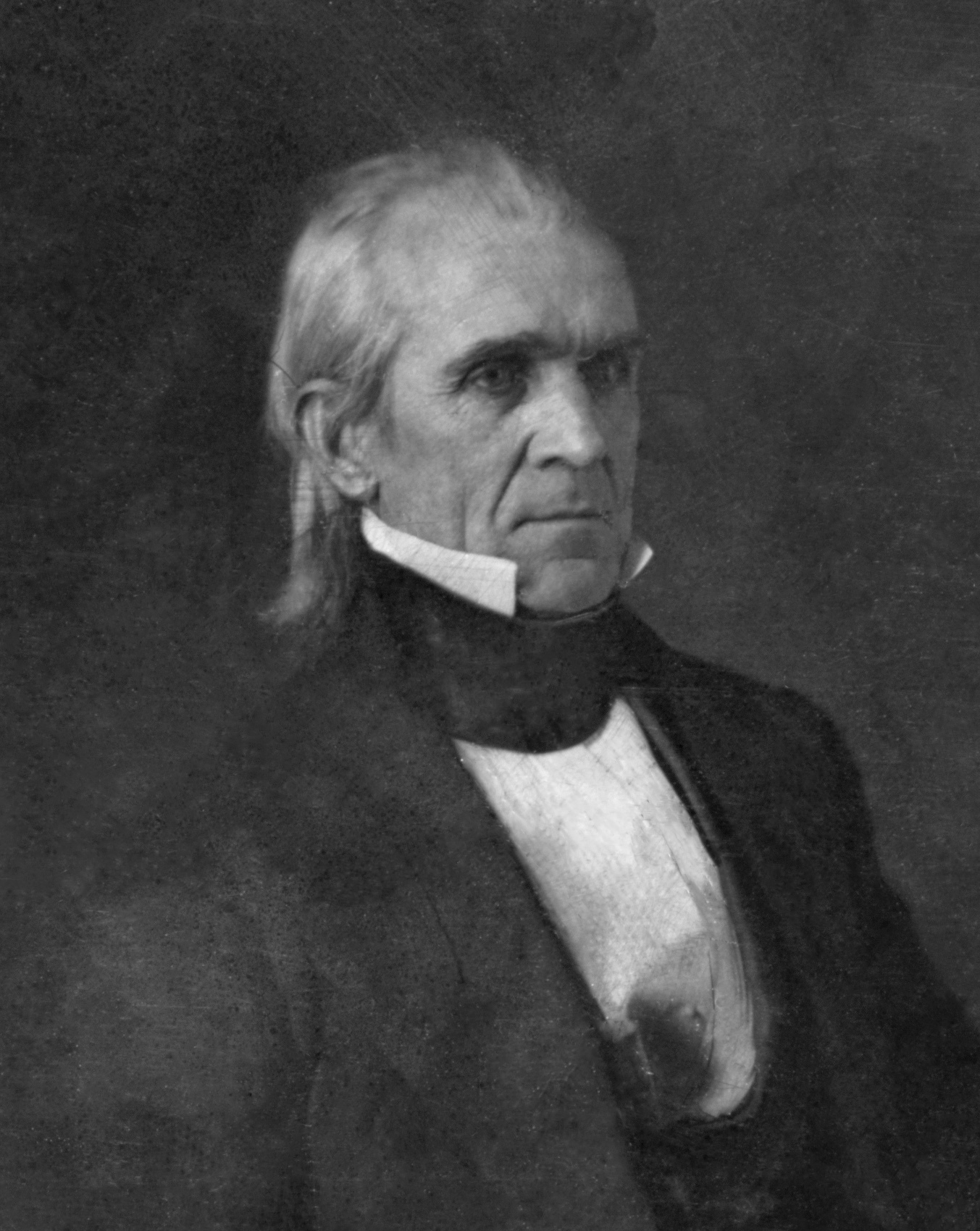

James K. Polk (1795-1849) was born in North Carolina but spent most of his political life in Tennessee. He earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and read law in Nashville under Felix Grundy.

After serving as a clerk to the Tennessee State Senate, Polk was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives where he ascended to the position of speaker of the House, the only future U.S. president to do so. As speaker, he used the gag rule to stifle debate over petitions to eliminate slavery, a rule that, under constant attack by John Quincy Adams, was eliminated the year before Polk became president.

Polk served as governor of Tennessee before being elected to the presidency. When nominated by the Democrat Party after it had deadlocked, he was considered to be a “dark horse,” or unexpected, candidate. The nation's 11th president, Polk served a single term from 1845 to 1849.

Polk’s policies resulted in acquisition of parts of Mexico

Polk was a protégé of fellow Tennessean Andrew Jackson and was nicknamed “Young Hickory” after his mentor who was known as “Old Hickory” for his toughness. Polk, who believed strongly in manifest destiny and who had run on a platform of westward expansion, is sometimes said to be the only presidential candidate who fulfilled all of his electoral promises.

He helped reduce tariffs, established a “Constitutional Treasury” in which the government would deposit its funds in its own repositories (Greenstein 2010, 727), successfully waged war (opposed by Abraham Lincoln) against Mexico that resulted in significant territorial acquisition, and helped negotiate the boundaries of Oregon.

Although Polk advocated strict interpretation of the U.S. Constitution with respect to domestic affairs, he exercised his powers of commander in chief to their fullest and took actions that goaded Mexico into war by sending U.S. troops into disputed territory. This resulted in the expansion of the U.S. to the Rio Grande in the South and to the Pacific Ocean in the West as recognized in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). This treaty provided that individuals in those parts of Mexico that were to be incorporated into the United States “shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty and property, and secured in the free exercise of their religion without restriction” (Pinheiro 2003, 94).

Addition of Mexican territory heightened slave questions

Polk, who owned slaves and believed that owners had the right to take slaves into U.S. territories, opposed the Wilmot Provision, which would have banned slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico.

Although this provision was not adopted, Polk had prepared a veto message in which he had stated that “the blessings of liberty [of the slaveowner] may be put in jeopardy or lost forever” (Mann).

Polk was a strong supporter of the separation of church and state and appointed Catholic priests to support U.S. soldiers. His wife also provided money to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who were moving to Utah (“Project Compiling President Polk’s Legacy 2019). In another development, Polk appointed Jacob I. Martin as an official U.S. charge d’affaires to the consulate established by Vatican City in New York.

First Amendment issues

Supreme Court upholds state law limiting Catholic funerals

The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Barron v. Baltimore (1833) that the provisions of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, only limited the national government and not the states. This was reinforced in a case before the Supreme Court during Polk's presidency, Permoli v. New Orleans, 44 U.S. 589 (1845). In Permoli, the high court refused to overturn a New Orleans ordinance limiting Catholic funerals to a single chapel within the city. As in Barron, the high court ruled that it was up to “state constitutions and laws” to protect the free exercise rights against state and local infringements.

In another case during Polk's term that did not mention the First Amendment but dealt with an issue related to it, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in White v. Nicholls, 44 U.S. 266 (1845), that individuals, in this case a customs collector, could collect libel judgments if they could establish that letters sent to the president and other public officials questioning their fitness were motivated by malice.

Polk appoints Woodbury, Grier to Supreme Court

Polk had pledged to serve only a single term and did not run for reelection. He took his job quite seriously, worked long hours, and died of cholera not long after he left office.

Polk appointed two Supreme Court justices. They were Levi Woodbury, who served from 1845 to 1851, and Robert Grier, who served from 1846 to 1870. Polk’s attorney general, James Buchanan, later served a term as president.

Polk is generally regarded as one of the most effective presidents from Jackson through Lincoln. Although Polk had successfully expanded U.S. territories, some of these acquisitions aggravated the sectional tension between free states and slave states that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 12, 2023.