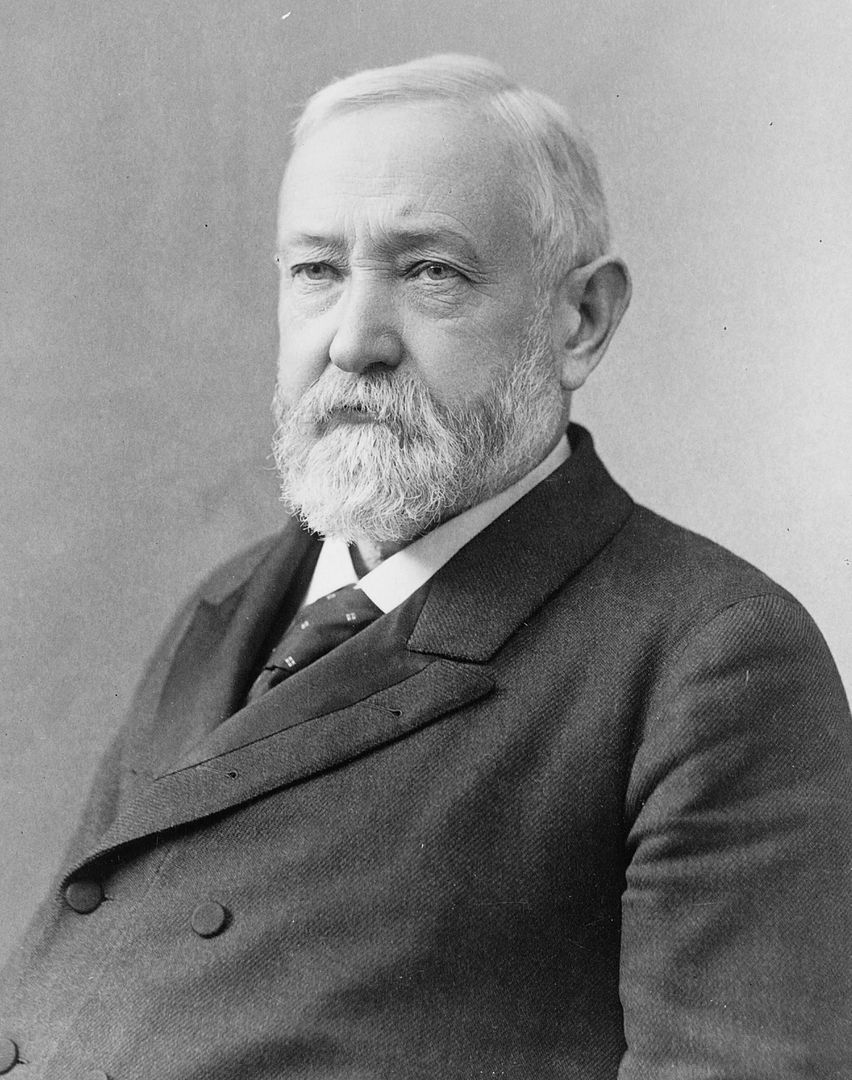

Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901), the grandson of former president William Henry Harrison and the great-grandson of Benjamin Harrison V, who had signed the Declaration of Independence.

He served as the 23rd president from 1889 to 1893.

Harrison defeated Grover Cleveland in the electoral college (albeit not in the popular vote) in 1888, but lost both the popular and electoral college vote to him in the 1892 presidential election.

Born in Ohio, Harrison attended Farmers’ College, completed his bachelor’s degree at Miami of Ohio, read law and was admitted to the bar.

After he married, Harrison moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, where he transitioned from supporting the Whig Party to the Republican Party. He served in the Union Army during the Civil War, inspired his men in combat, and was promoted to brevet brigadier general. He was chosen to be a U.S. senator from Indiana from 1881 to 1887.

In a speech that he delivered in Indianapolis on Aug. 7, 1888, when running for president, Harrison observed that: “The Republican party did not organize for spoils; it assembled about an altar of sacrifice and in a sanctuary beset with enemies. You have not forgotten our early battle-cry — ‘Free speech, a free press, free schools and free Territories.’ We have widened the last word; it is now ‘a free Nation’” (Speeches of Benjamin Harrison, p. 78).

Harrison was a devout Presbyterian. In his inaugural address, he drew upon Presbyterian theology when he proclaimed that his oath “taken in the presence of the people becomes a mutual covenant. The officer covenants to serve the whole body of the people by a faithful execution of the laws, so that they may be the unfailing defense and security of those who respect and observe them, and that neither wealth, station, nor the power of combinations shall be able to evade their just penalties or to wrest from them a beneficent public purpose to serve the ends of cruelty or selfishness” (Inaugural Address, March 4, 1889).

As president, Harrison succeeded in getting the Sherman Antitrust Act adopted in 1890. His support for the Blair Education Bill, which would have provided federal aid for education (particularly in the South), failed. Harrison did strike a blow for presidential authority when his decision to assign a deputy U.S. marshal to defend Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field was vindicated by the Supreme Court in the case of In re Neagle (1890) under the president’s authority to take care that laws were faithfully executed (See "The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History," pp. 303-304).

School Bible readings, workplace speech debated in courts

Harrison was president prior to the time that the U.S. Supreme Court had applied the provisions of the First Amendment to the states via the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, thereby limiting the court’s interpretations of the First Amendment during this time period. There were, however, at least two state court decisions of note during his presidency.

In State ex rel. Weiss v. City of Edgerton (1890), the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled, much like the modern U.S. Supreme Court, that devotional reading from the King James Version of the Bible in public schools in the state violated state guarantees of freedom of religion.

In a less liberal vein in McAuliffe v. Mayor of New Bedford (1891), the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (1892) limited workplace speech when it upheld the firing of a police officer for soliciting money and belonging to a political committee.

Supreme Court upheld withdrawing voting rights from polygamists

The U.S. Supreme Court also delivered some important decisions during Harrison’s term.

In the area of religion, in Davis v. Beason (1890), it upheld an Idaho law directed against members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints withdrawing the right to vote from those who would not forswear polygamy.

In a much quoted, and much disputed, opinion in Church of the Holy Trinity v. Unites States (1892), which involved the application of an immigration law to an English clergyman, Justice David Brewer declared that the United States was a “Christian nation.”

Harrison agreed with laws outlawing polygamy, stopping funds for church schools

Harrison agreed with national efforts to combat polygamy, which he thought was a form of paganism. Although he issued pardons to some polygamists, he resisted the effort to grant statehood to Utah (See See “Benjamin Harrison: The Religious Thought and Practice of a Presbyterian President” by William C. Ringenberg, pp. 175-189,).

Harrison further supported General Thomas J. Morgan, a former Baptist minister whom he had appointed as Indian commissioner and who believed strongly in separation of church and state, in efforts to withdraw federal funding to Native American Indian schools that were operated by the Roman Catholic Church (Ringenberg 1986, 183-184).

Harrison also sought to control the use of the U.S. mail to send lottery cards or advertise for such gambling. The Supreme Court decision In re Rapier (1892) held that the congressional law for which Harrison had successfully lobbied did not violate freedom of the press.

Harrison appoints four to Supreme Court

Harrison made four Supreme Court appointments. They were David J. Brewer, Henry Billings Brown, George Shiras Jr. and Howell Jackson. Harrison also appointed William Howard Taft, who would later be elected president and serve as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, as solicitor general.

Harrison remained active in retirement. In addition to continuing his work as a lawyer, he delivered public speeches, and, in 1900, served at an ecumenical missionary conference. There he joined President William McKinley and then New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt and gave a speech in which he extolled “the work of spreading Christianity throughout the world” (See "Civil Religion and the Gilded Age Presidency: The Case of Benjamin Harrison").

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 20, 2023.