Most state and federal anarchy statutes in the United States were passed in the early 20th century in response to the growing visibility of anarchists, who believed in replacing coercive governments with forms of voluntary cooperation.

Although most U.S.-born anarchists at the time were peaceful (Fine 1955: 778), anarchists from Europe, particularly from Germany and Russia, sometimes advocated violence. The public therefore often associated immigrants with anarchism.

Much of the popular reaction toward anarchists appears to foreshadow, and possibly set the stage for, the later “Red Scares” focusing on the perceived threat of communists.

Haymarket Riot, presidential assassination led to restrictions on anarchists’ First Amendment freedoms

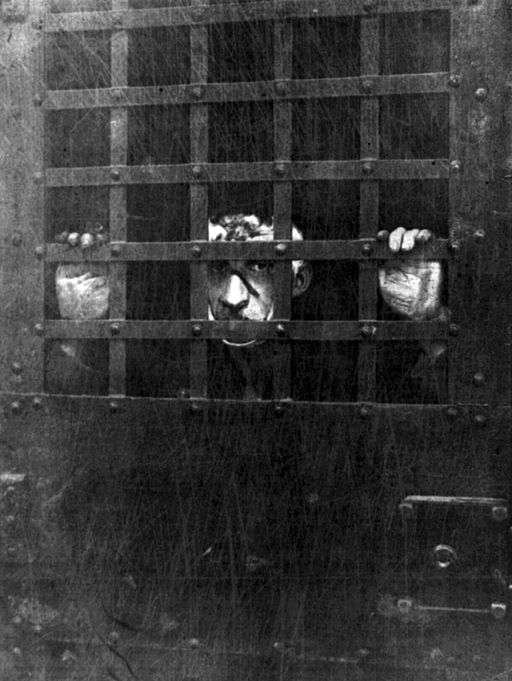

Johann Most immigrated to the United States in 1882 and became anarchism’s most vocal American proponent. He helped establish the International Working People’s Association in 1883, calling for the “[d]estruction of the existing class rule, by all means, i.e., by energetic, relentless, revolutionary and international action” (Ibid.: 779).

The Haymarket Riot in Chicago on May 4, 1886, generated fear of anarchism after someone from a group of labor protesters seeking an eight-hour workday threw a bomb into a group of policemen. The riots led to restrictions on freedom of speech, press, and assembly and resulted in convictions for several labor leaders that the Illinois Supreme Court upheld in Spies v. Illinois (1887).

At the time, the First Amendment did not apply to the states, as it would after Gitlow v. New York (1925).

The anarchists’ reputation received another blow when Leon F. Czolgosz, an unstable anarchist who had listened to a speech by anarchist and socialist Emma Goldman, assassinated President William McKinley on Sept. 6, 1901.

Most, Goldman, and others were charged with having conspired with Czolgosz. Most was convicted under New York law for having reprinted an article advocating tyrannicide. Elsewhere, throughout the country, prosecutors went after anarchist communities.

Immigration Act excludes anarchists; deportation causes controversy

Congress adopted the Immigration Act of 1903, which excluded immigrants who were “anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of all governments, or of all forms of law, or the assassination of public officials” (Ibid.: 792).

This law generated considerable controversy, when the federal government attempted to deport John Turner, a British trade unionist found to possess a copy of a pamphlet by Johann Most.

Attorney Clarence Darrow, among others, stepped forward to help the newly formed Free Speech League — a precursor to the American Civil Liberties Union — press the free speech aspects of the case.

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal against deportation in United States ex. rel. John Turner v. Williams (1904).

Bad tendency test used to uphold anarchy conviction

In Gitlow, the Court upheld a conviction of socialists under New York’s criminal anarchy law, which the state had adopted in 1902. (New Jersey and Wisconsin had adopted similar legislation.)

Although the Court used the decision to indicate that it would now apply First Amendment free speech rights to the states, the majority applied the bad tendency test, which allowed for prosecution of speech that had a “bad tendency” to promote illegal action.

They used the test to uphold the conviction not of an anarchist but of a socialist for distributing copies of the Left-wing Manifesto advocating overthrow of the government by force.

Over time, including in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), which struck down an Ohio criminal syndicalism act, the Court would make clearer distinctions between the legal advocacy of abstract doctrine (protected speech) and incitement to imminent lawless action (unprotected by the First Amendment).

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.