The Supreme Court decision in United States v. Press Publishing Co., 219 U.S. 1 (1911), overturned the indictment of several individuals charged with the federal crime of libel.

Legal commentator Michael Gibson has designated this decision “the last gasp of seditious libel” and observed that a contemporary law journal described it as “a landmark, one of the substantial guarantees of the continued freedom of the press.”

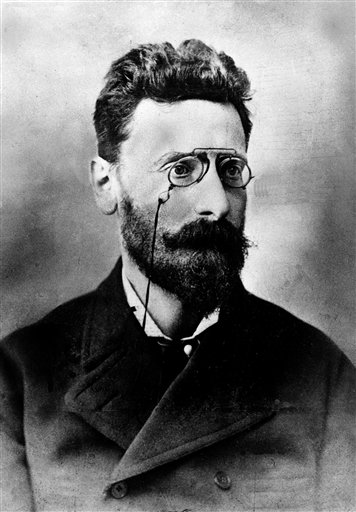

Pulitzer and other newspaper publishers charged with criminal libel for Roosevelt stories

Theodore Roosevelt initiated libel prosecutions against Joseph Pulitzer and the other publishers of newspaper stories that had alleged that, while serving as president, he had profited from the sale of the Panama Canal.

He launched federal prosecutions using New York state law on the theory that the Assimilative Crimes Act of 1898, which applied state laws to small federal enclaves within a state’s boundaries, permitted prosecution of libelous publications delivered there — in this case, to the federal military enclave at West Point, New York, and to a federal post office in New York City, also considered a federal enclave.

Supreme Court quashes libel indictments

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of The New York World, was among newspaper publishers that were indicted by a federal grand jury for criminal libel after stories about Theodore Roosevelt. The Supreme Court, recognizing there was no federal criminal libel law, quashed the indictments.

Chief Justice Edward White’s opinion for a unanimous Court quashed the indictments, recognizing that there was no federal crime of libel. White said that the purpose of the Assimilative Crimes Act was to fill in lacunae in federal criminal laws by enforcing the criminal laws of the state surrounding the federal enclave rather than to provide an alternate forum for prosecution.

This left Roosevelt with the option of pursuing his case in state court, but New York had designed its libel laws to limit prosecutions to a single venue so that a decision in one was valid in all others.

White did acknowledge that his ruling would not apply to a case “where an indictment was found in a court of the United States for a crime which was wholly committed on a reservation, disconnected with acts committed within the jurisdiction of the State, and where the prosecution for such crime in the courts of the United States instead of being in conflict with the applicable state law was in all respects in harmony therewith.”

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.