Freedom of speech often suffers during times of war. Patriotism at times devolves into jingoism and civil liberties take a backseat to security and order.

The pattern has been consistent in American history from the Revolutionary War to the modern-day War on Terror after the infamous terrorist strikes on U.S. soil on Sept. 11, 2001.

Writing for a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes declared in Schenck v. United States (1919) that “[w]hen a nation is at war, many things that might be said in times of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.”

In other words, the Supreme Court declared that the government could restrict speech more in times of war than in times of peace.

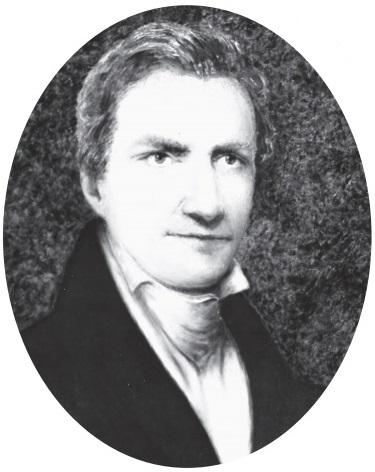

Matthew Lyon was the first person to be put on trial for violating the Alien and Sedition Acts, including the Sedition Act of 1798, after publishing criticism of President John Adams. The Sedition Act of 1798 criminalized the “writing, printing, uttering or publishing [of] any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings about the government of the United States.” Lyon was sentenced to four months in jail. While imprisoned, he was elected to represent Vermont in Congress. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Restrictions on speech during Revolutionary War Era and early years

The Revolutionary War era featured numerous restrictions on free speech and free press. Those who were considered loyal to the King of England – loyalists – were subject to a host of onerous restrictions by colonial leaders. Some colonies passed laws declaring it treasonous to support the British King.

Even after the United States declared its independence from England, restrictions on speech continued. It is one of the great ironies of history, that many of the same political leaders that ratified the U.S. Constitution and the U.S. Bill of Rights (including the First Amendment) were the same leaders who passed the Sedition Act of 1798 – a law inimical to freedom of speech. The law and its companion Alien Acts were a product of the times – a silent war with France.

The Sedition Act of 1798 criminalized the “writing, printing, uttering or publishing [of] any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings about the government of the United States.” The law was used by the Federalist Party to silence Democratic-Republic newspaper editors – men like Matthew Lyon, Benjamin Bache, and William Duane.

Prominent Democratic politician Clement L. Vallandingham faced imprisonment and banishment for delivering an anti-war speech that was highly critical of President Lincoln. He called the President “King Lincoln” and criticized the war in stark terms. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

Civil War censorship

The Civil War period was also a time of government repression of freedom of speech and the press. President Abraham Lincoln seized the telegraph lines, suspended habeas corpus and issued an order prohibiting the printing of war news about military movements without approval. People were arrested for supporting the Confederacy – even wearing buttons or singing Confederate songs

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the Lincoln administration censored telegraph dispatches to and from Washington. His administration created military tribunals to deal with disloyalty.

Government officials shut down newspapers, such as the Chicago Times, for criticizing President Lincoln and his cabinet members. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton approved of the destruction of a Washington, D.C. newspaper called the Sunday Chronicle.

Prominent Democratic politician Clement L. Vallandingham faced imprisonment and banishment for delivering an anti-war speech that was highly critical of President Lincoln. He called the President “King Lincoln” and criticized the war in stark terms.

Several congressmen attempted to expel Ohio Rep. Alexander Long from Congress for an unpatriotic speech made on the House floor. One congressman stated: “A man is free to speak so long as he speaks for the nation … [but not] … against the nation on this floor.”

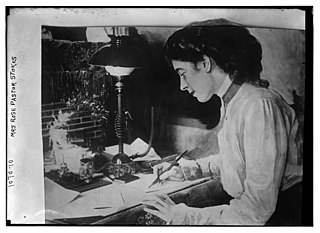

Rose Pastor Stokes, an activist and writer, was prosecuted under the Espionage Act of 1917, in part, for writing to a newspaper: “I am for the people and the government is for the profiteers.” The Act criminalized attempting to cause insubordination to the war effort, willfully attempting to cause insurrection and obstructing the recruiting or enlistment of potential volunteers. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

World War I speech repression

World War I featured a pattern of serious repression of speech considered disloyal. Legal historian Paul Murphy explained in his scholarship that the speech repressions during World War I created the modern civil liberties movement.

Congress, along with President Woodrow Wilson, became concerned with internal dissent, particularly with those whom they suspected of sympathizing with the Germans and the Russians. It passed the Espionage Act of 1917, which has been described as an “overt assault upon First Amendment freedoms.”

The law criminalized attempting to cause insubordination to the war effort, willfully attempting to cause insurrection and obstructing the recruiting or enlistment of potential volunteers. Another section of the law gave the postmaster general the power to ban from the mail any material “advocating or urging treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance to any law of the United States.”

Congress passed an amendment to the Espionage Act — called the Sedition Act of 1918 — which further infringed on First Amendment freedoms. The law prohibited:

Uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language intended to cause contempt, scorn … as regards the form of government of the United States or Constitution, or the flag or the uniform of the Army or Navy … urging any curtailment of the war with intent to hinder its prosecution; advocating, teaching, defending, or acts supporting or favoring the cause of any country at war with the United States, or opposing the cause of the United States.

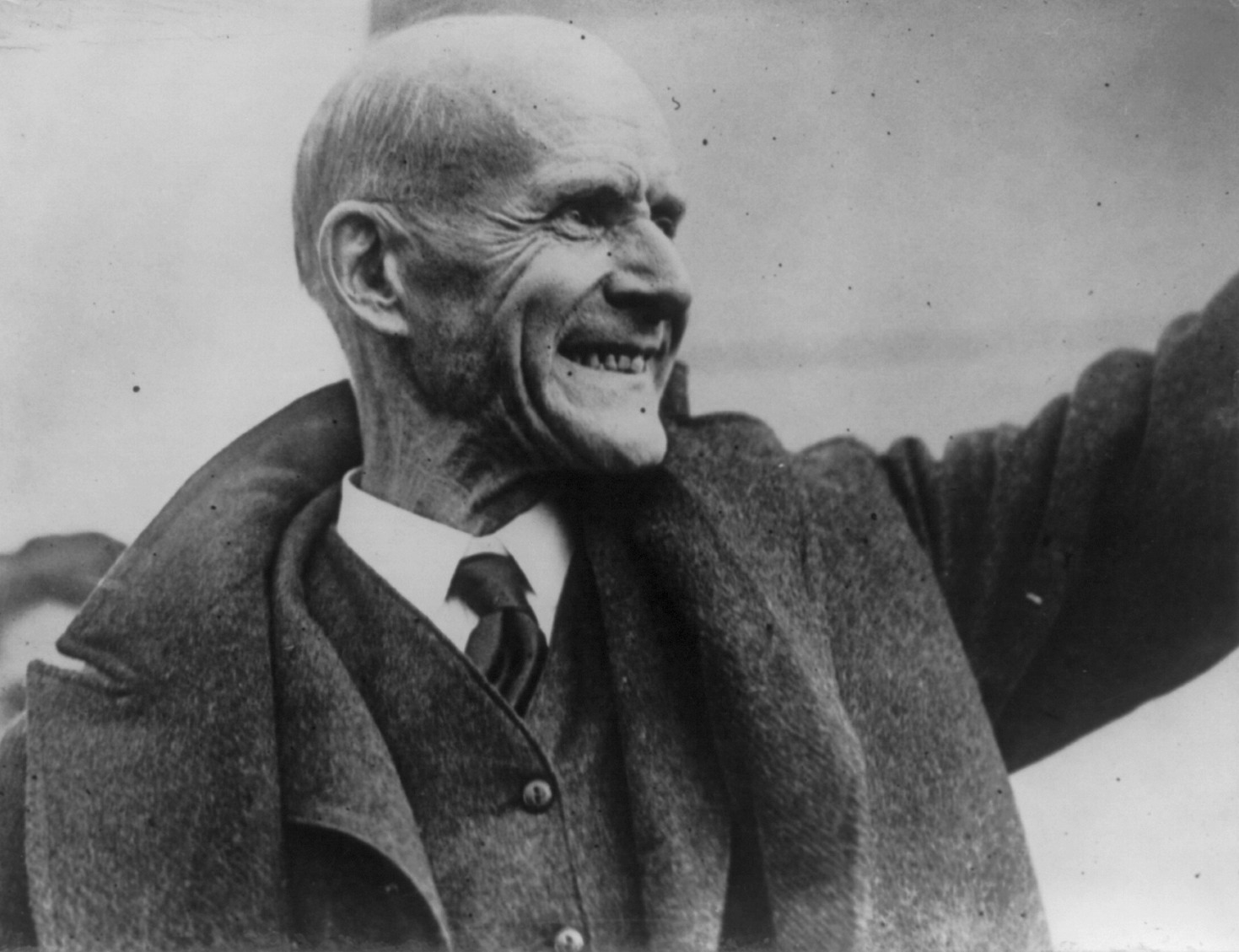

In one of the more high-profile examples of censorship during this time period, officials arrested famed labor organizer and socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs who criticized the war and the draft. Debs famously stated during his speech in Canton, Ohio: “You need at this time especially to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.”

Federal officials charged Debs with violating the Espionage Act of 1917. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld his conviction in Debs v. United States (1919).

Rose Pastor Stokes was prosecuted, in part, for writing to a newspaper: “I am for the people and the government is for the profiteers.”

Murphy details numerous examples of draconian restrictions on free speech during this time period, including:

- Authorities in Pittsburgh banned music by the German composer Ludwig van Beethoven during the course of the war.

- The Los Angeles Board of Education prohibited all discussions of peace.

- An Ohio farmer, John White, was imprisoned for stating that soldiers in American camps were “dying off like flies” and that the “murder of innocent women and children by German soldiers was no worse than what the United States’ soldiers did in the Philippines.”

- A Minnesota man was arrested under a state espionage law for criticizing women knitting socks for soldiers, saying: “No soldier ever sees these socks.”

- Twenty-seven South Dakota farmers were convicted for sending a petition to the government objecting to the draft and calling the conflict a “capitalist war.” (Hudson, citing Murphy).

During World War II, the government continued its pattern of overreacting and limiting civil liberties and First Amendment rights during wartime. The government committed perhaps the greatest civil liberties violation in the history of the country since slavery — the internment of 110,000 Japanese-Americans in concentration camps. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this travesty in Korematsu v. United States (1944). In this photo, the 237 Japanese, who were evacuated from Bainbridge Island in Washington State showed mixed emotions as they trooped down a ferry landing onto a boat, which took them to Seattle en route to California in 1942. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

World War II and Korean War

The pattern of government overreaction continued during the second World War and the Korean War. During this time, the government committed perhaps the greatest civil liberties violation in the history of the country since slavery — the internment of 110,000 Japanese-Americans in concentration camps. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this travesty in Korematsu v. United States (1944).

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover emergency authority to censor all news and control all communications in and out of the country.

Before the start of World War II, Congress passed the country’s first peacetime sedition law, called the Alien Registration Act of 1940, sometimes called the Smith Act because Title I of the law was named after Rep. Howard W. Smith of Virginia.

The law prohibited advocating or teaching the “propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence” and the printing or publishing of any material advocating or teaching the violent overthrow of the country.

In Dennis v. United States (1951), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the conviction of 12 people for Communist Party activity. The Court wrote: “To those who would paralyze our Government in the face of impending threat by encasing it in a semantic straitjacket we must reply that all concepts are relative.” Many view this decision as a product of the times when the Court was not sensitive enough to free-speech concerns.

During the Vietnam War, the government again assaulted free speech in many dimensions. In perhaps the most important First Amendment case during this era, the U.S. Supreme ruled in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) that the government could not prohibit The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing a series of articles about some highly classified documents, called “the Pentagon Papers,” about the U.S. government’s role in the Vietnam War. In this 1971 photo, workers in the New York Times composing room in New York look at a proof sheet of a page containing the secret Pentagon report on Vietnam. (AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War witnessed assaults on free speech in many dimensions. Protestors outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention suffered at the hands of a violent police force.

Civil rights leader Julian Bond, a member of the Georgia legislature, was forced to battle all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court to keep his legislative seat, because he criticized the Vietnam War. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Bond v. Floyd (1966) that Georgia officials could not expel Bond from his seat for his political views.

“The manifest function of the First Amendment in a representative government requires that legislators be given the widest latitude to express their views on issue of policy,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote for the Court. “Just as erroneous statements must be protected to give freedom of expression the breathing space it needs to survive, so statements criticizing public policy and the implementation of it must be similarly protected.”

In perhaps the most important First Amendment case during this era, the U.S. Supreme ruled in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) that the government could not prohibit The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing a series of articles about some highly classified documents, called “the Pentagon Papers,” about the U.S. government’s role in the Vietnam War.

In his opinion, Justice Hugo Black wrote: “The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

Sen Patrick Leahy D-Vt. peers over the shoulder with his camera as President Bush signs the Patriot Act Bill during a ceremony in the White House East Room in 2001. The law was passed quickly in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Several provisions of the Patriot Act impact First Amendment freedoms in a fundamental way. One provision – so-called Section 215 – allowed government officials the ability to read business records, library records, health-care records, logs of Internet service providers and other documents and papers without the traditional protections that individuals have. (AP Photo/Doug Mills, used with permission from the Associated Press)

9/11 and the Patriot Act

The terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001 seared the collective conscience of the country and provided the perfect storm for government legislators to push through comprehensive federal legislation known as the United and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism. The law, passed only 45 days after the attacks, is better known as the U.S.A. Patriot Act.

Several provisions of the Patriot Act impact First Amendment freedoms in a fundamental way. One provision – so-called Section 215 – allowed government officials the ability to read business records, library records, health-care records, logs of Internet service providers and other documents and papers without the traditional protections that individuals have. Several lawsuits were filed challenging Section 215 on First Amendment and other grounds. The provision has since been modified.

Another provision of the Patriot Act broadened the definition in federal law of providing “material support or resources” to terrorist organizations. That provision, Section 805(a)(2)(B), added “expert assistance or advice” to the definition of “material support” to terrorists. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of that provision in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010).

Conclusion

American history confirms that in times of war, freedom of speech suffers. The understandable push for security and order unfortunately has caused excess efforts at branding many who dissent as disloyal. First Amendment scholar Thomas Emerson wrote it well in 1968: “The full protection theory of the first amendment is viable in wartime, but it needs further support to survive as a reality.” (1011).

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.