The Supreme Court addressed numerous First Amendment issues raised by political actions taken by the U.S. government during World War I — although the Court weighed in only after the hostilities ended. While the Court upheld the convictions of many individuals who objected to the war, their cases also laid the groundwork for contemporary First Amendment law.

President Woodrow Wilson boasted in his 1916 reelection campaign that he had kept America out of the war engulfing Europe. A month after his second inauguration, however, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. German U-boats had sunk three American vessels as part of intense submarine warfare to interdict munitions and supply shipments from the United States to the Allies.

Woodrow Wilson targeted First Amendment freedoms during World War I

In his speech to Congress, Wilson threatened “stern repression” against any acts of disloyalty to the country, and he soon proposed an espionage act, the first law targeting disloyal expression since the infamous Sedition Act of 1798.

Wilson, never one to tolerate criticism, justified the legislation by arguing, among other points, that disloyal individuals had themselves sacrificed their rights to civil liberties. His proposal set the tone for arguably one of the most repressive periods in American history with respect to speech and press freedoms. “Ironically,” as constitutional scholars Melvin Urofsky and Paul Finkelman (2002) note, “the war to make the world safe for democracy triggered the worst invasion of civil liberties…in the nation’s history” (p. 613).

WWI speech restrictions led to first Supreme Court cases about public criticism of war

The issue of whether the government could restrict public criticism of a war because it might undermine support for the war effort was not new when the United States entered World War I, and it has recurred in every subsequent war, including the War on Terror. World War I was unique, however, in that it was the first time the issue was addressed by the Supreme Court.

A series of decisions in 1919 launched a process of judicial and scholarly debate that shaped interpretations of First Amendment protections thereafter.

Within weeks of declaring war, Congress began debating provisions of what became the Espionage Act of 1917. Contrary to the conventional wisdom’s holding that Congress attempted to suppress all criticism of the war and the military draft, Congress showed sensitivity to free speech issues and clearly rejected several key measures proposed by the Wilson administration.

Congress refused Wilson’s demand for press censorship powers

The most intensely debated of these was a provision that would have punished the wartime publication of any information that the president declared might be useful to the enemy.

Despite Wilson’s pleas that press censorship was necessary to public safety, the House voted against the provision, 184-144. Thirty-six Democrats broke ranks with the president.

Final version of Espionage Act had penalties for disloyal speech

The final version of the act made it a crime in wartime to make false statements with intent to interfere with the military effort, to cause or attempt to cause disloyalty or refusal of duty in the armed forces, or to obstruct military recruitment and enlistment efforts. Violators faced 20-year maximum prison terms. The postmaster general was authorized to exclude from the mails any material in violation of these provisions of the act.

Congressional debate transcripts reveal considerable concern about the importance of free speech, even (or perhaps especially) in wartime. But after passage, attention turned to the Justice Department, the federal agency responsible for enforcement. Any hopes for prosecutorial restraint quickly dissipated in late 1917 when Attorney General Thomas Gregory warned dissenters not to expect mercy from “an outraged people” and “an avenging government.”

Wilson administration began campaign for super-patriotism

President Woodrow Wilson established a Committee on Public Information during World War I whose dominant theme was a demand for conformity and super-patriotism. This poster from 1917 urges workers to support the war effort. (From the Library of Congress, public domain)

The Wilson administration had been engaging in inflammatory rhetoric to foster and then exacerbate a state of public outrage, necessitated by the absence of any direct German attack on the United States.

Wilson established a Committee on Public Information (CPI) that flooded the nation with materials whose dominant theme was a demand for conformity and super-patriotism. Many communities banned German-language teaching and German-language books, and citizens of German descent were often subjects of vigilante action.

Thousands of political dissidents, pacificts indicted under Espionage Act; 45% convicted

The most frequent targets of federal prosecutions were political dissidents, leftist radicals, and pacifists. Ultimately thousands were indicted; nearly 45 percent were convicted. In this atmosphere, federal judges proved something other than fearless bulwarks of First Amendment freedoms, though there were scattered exceptions, most notably federal district judge Learned Hand.

Appeals were often delayed by a Justice Department not eager to have the constitutionality of these federal laws addressed by the Supreme Court. It was not until early 1919 — after hostilities had ended — that the Court finally came face to face with the First Amendment in a series of cases challenging the Espionage Act.

Espionage Act case involving anti-draft leaflets reached Court

At the time, there were few judicial precedents regarding the meaning of the First Amendment, and most judges assumed it reflected English common law, which allowed punishment if speech had a “bad tendency” to lead to illegal action, regardless of whether criminal action actually ensued.

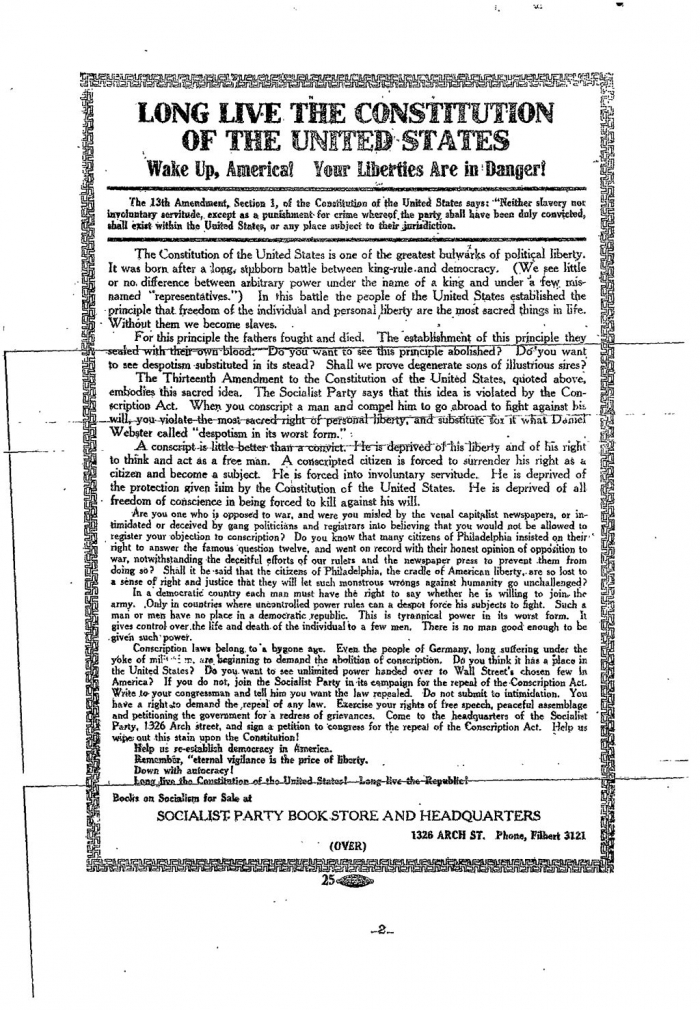

This is the front page of the pamphelt published by Charles Schenck that resulted in his conviction under the Espionage Act. (Public domain)

The vast majority of federal courts followed the “bad tendency” test when called upon to interpret and apply the provision of the Espionage Act.

Schenck v. United States (1919) stemmed from the prosecution of Charles Schenck for violating the Espionage Act’s prohibition on obstruction of military recruiting. Schenck, the general secretary of the Socialist Party, printed anti-draft leaflets that were sent to potential draftees. He argued that the Espionage Act interfered with his First Amendment right to discuss war issues publicly.

Supreme Court upheld espionage conviction under ‘clear and present danger’ test

A unanimous Supreme Court rejected Schenck’s appeal. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote the opinion that gave American law the famous “clear and present danger” test. Holmes argued that the speaker’s intent as well as the context in which the remarks were made must be examined, finding that wartime is less conducive to free speech than is peacetime. He wrote: “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.”

While Holmes’s “clear and present danger” approach seems more protective of speech than the dominant “bad tendency” test, many scholars argue that Holmes was not attempting to supplant the latter approach. He simply gave it another name.

In two subsequent cases, Frohwerk v. United States (1919) and Debs v. United States (1919), Holmes wrote opinions making no mention of clear and present danger, summarily rejecting First Amendment claims, and upholding the convictions of Jacob Frohwerk (a German-language newspaper editor who published a series of anti-war articles) and Eugene Debs (the Socialist Party’s 1912 presidential candidate who received close to a million votes nationwide).

Holmes, Brandeis began to support dissident speech as protected under First Amendment

In the months that followed, as the result of a series of letters and conversations with Hand and Harvard law professor Zechariah Chafee Jr., Holmes’s views about free speech began to change. When the Court in Abrams v. United States (1919) upheld convictions under the Sedition Act of 1918, Holmes dissented and produced perhaps his greatest piece of rhetoric.

Jacob Abrams and others had written and distributed leaflets criticizing Wilson’s decision to send U.S. troops to fight in Soviet Russia. Abrams called for a general strike to protest this allegedly anti-Bolshevik policy. He was indicted under the Sedition Act (an amendment to the Espionage Act), which made it a crime to “incite, provoke or encourage resistance to the United States” or to conspire to urge curtailment of munitions production with intent “to cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of the war.”

In his dissent, joined by Justice Louis D. Brandeis, Holmes’s eloquence reached new heights. He conceded the logic behind persecution for expressions of opinion, but then added:

“When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

Brandeis said only speech leading to imminent lawless action should be punished

In the decade that followed, Holmes continued to dissent, as did Brandeis. Some of Brandeis’s opinions are as important as those of Holmes in their emphasis (certainly shared by Holmes) on the importance of imminent lawless action as the only justification for punishing speech.

The current, highly speech-protective test for the constitutionality of government regulation of speech advocating illegal activity — Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) — is deeply rooted in these dissents.

Federal judge Hand tried to naorrowly construe Espionage Act

Today’s view also has roots in an opinion by Hand in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917), which predates Schenck by two years and represents one of the few efforts by a federal judge in the World War I era to construe the Espionage Act narrowly by focusing on express advocacy of illegal activity.

Espionage Act remains in effect

Congress repealed the Sedition Act of 1918 on December 13, 1920. The Espionage Act of 1917 remains in effect.

On May 21, 2006, Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales, appointed by President George W. Bush, raised the possibility that New York Times journalists who published stories revealing secret National Security Agency surveillance of calls between individuals in the United States and alleged terrorists abroad might be prosecuted for publishing classified information. The basis for any prosecution would be the Espionage Act of 1917.

This article was originally published in 2009. Philip A. Dynia is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department of Loyola University New Orleans. He teaches constitutional law and judicial process as well as specialized courses on the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment.