This excerpt from Christopher Finan’s "From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act" is published here with the kind permission of the author and Beacon Press. Copyright 2008.

On the evening of November 7, 1919, Mitchel Lavrowsky was teaching a class in algebra to a roomful of Russian immigrants at the Russian People’s House, a building just off Union Square in New York City. The fifty-year-old Lavrowsky was also Russian. He had been a teacher and the principal of the Iglitsky High School in Odessa before emigrating to the United States and now lived quietly with his wife and two children in the Bronx. Lavrowsky had applied for American citizenship. But that didn’t matter to the men who entered his classroom with their guns drawn around 8 p.m. They identified themselves as agents of the Department of Justice and ordered everyone to stand. One of them advanced on Lavrowsky and instructed him to remove his eyeglasses. He struck Lavrowsky in the head. Two more agents joined the assault, beating the teacher until he could not stand and then throwing him down the stairwell. Below, men hit him with pieces of wood that they had torn out of the banister.

Lavrowsky soon had company on the stairs. There were several hundred people in the Russian People’s House that night, most of them students. After they were searched and relieved of any money they might be carrying, the students were ordered out of their classrooms and into a gauntlet of men who struck some of them on the head and pushed them down the stairs toward the waiting police wagons. Students were grabbed as they approached the school and dragged inside. Some were beaten in the street. Meanwhile, with the help of New York City police detectives, the Justice Department men began to tear the place apart, breaking furniture, destroying typewriters, and overturning desks and bookshelves until the floor was covered in a sea of paper. When they judged that there was nothing useful left, they carted off two hundred prisoners to the Department of Justice’s offices in a building across from City Hall. The Russians were questioned about their connection to the Union of Russian Workers, which rented a room in the Russian House. The agents discovered that only thirty-nine were members of the group and released the rest. Mitchel Lavrowsky was sent home at midnight with a fractured head, shoulder, and foot.

The roundup of Russians continued through the night and into the next day. The police burst into apartments and dragged people from their beds. Sometimes they had arrest warrants, but usually they simply arrested everyone they found. In the end, the Department of Justice had grabbed more than one thousand people in eleven cities. Approximately 75 percent of those arrested were guilty of nothing more than being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and many were quickly released. Others were not so lucky. Nearly one hundred men were locked up in Hartford, Connecticut, for almost five months. Many of them were denied access to a lawyer or even knowledge of the charges against them. Probably half were Russian workers whose only crime was that they could not speak English. When a lawyer finally succeeded in getting inside the jail, ten of the men were released with no bail.

America cheered the November raids.

Revolutionary threat leads to Palmer Raids

World War I had ended a year earlier, and the country was enduring a wrenching conversion to peace. Unemployment surged as returning veterans sought to reclaim their old jobs. Many of them had been eliminated as the economy was retooled for war production, and now the war workers, too, were out of work. In the transition between war and peace, there were too few consumer goods. No new housing had been built in over eighteen months. As a result, at the moment when they could least afford it, Americans found themselves facing high inflation. It isn’t surprising that at a time when they were feeling so vulnerable, people began to worry about the danger of foreign radicalism. Radicalism was nothing new. The Socialist Party had existed here for many years. But the success of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 appeared to have launched a worldwide revolutionary threat that many people easily connected with the growing number of strikes in the United States — over 3,600 in 1919 alone. Although these strikes were driven by inflation, not radical ideology, employers did their best to paint their workers as subversives. The threat of revolution seemed to be confirmed in June when eight bombs exploded outside the homes of prominent men, including the new attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer. The nation demanded swift action. “I was shouted at from every editorial sanctum in America from sea to sea; I was preached upon from every pulpit,” Palmer recalled. “I was urged — I could feel it dinned into my ears — throughout the country to do something and do it now.”

The November raids were the result.

Launched on the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, they were followed by a second, even larger series of raids in January that seized over three thousand members of two new American parties, the Communist Party and the Communist Labor Party.

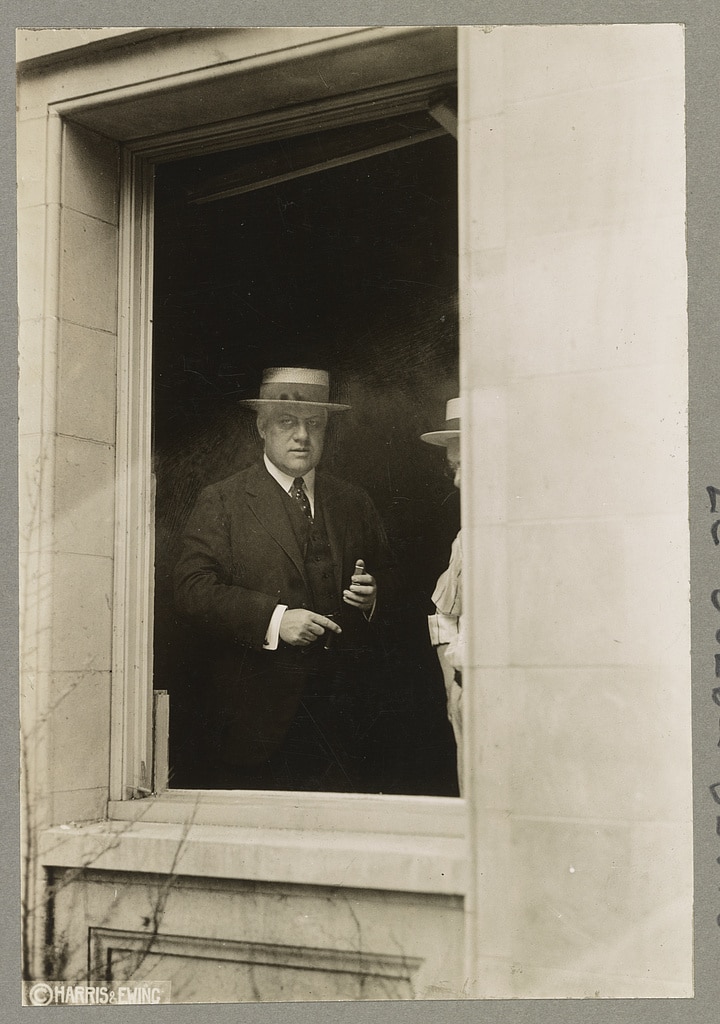

Alexander Mitchell Palmer, attorney general of the United States after World War I, was the namesake of the "Palmer raids." As anti-Communist sentiment grew, Palmer used the Alien and Sedition Acts as a basis to raid supposed communist, socialist and anarchist organizations. Palmer is pictured here through the window of his home in Washington, D.C. after it was bombed on June 2, 1919. (Photo via Library of Congress, public domain)

Although the Palmer Raids generated a lot of good publicity for the Department of Justice, they accomplished little. The government never discovered who was behind the June bombings. The radicals who were arrested in November and January were not charged with any crime. The Department of Justice would have been unable to take any action at all if Congress had not made it a deportable offense for an alien to belong to a group that advocated the violent overthrow of the government. The people who were arrested during the Palmer Raids were picked up not because of anything they had done but because of what they might do. In fact, many of those arrested and held for deportation did not believe in violence. The Union of Russian Workers had declared its belief in revolution when it was founded in 1907, but by 1919 it had largely become a social club whose members were unaware of its founding principles. The Department of Labor later canceled thousands of deportation orders issued to members of the Communist Labor Party on the grounds that it, too, was not a truly revolutionary party. In the end, the government succeeded in deporting only eight hundred of the more than four thou-sand people it had arrested.

Emma Goldman decries deportation as assault on free speech

But the government raids did achieve something important. They raised the issue of what freedoms are protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The First Amendment bars government from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” By targeting people for deportation based on their beliefs, the Palmer Raids had violated the First Amendment. Emma Goldman made this point during her deportation hearing in October 1919. Born in Russia, the fifty- year-old Goldman was one of the country’s most notorious radicals. Like many anarchists, she believed that violent acts were a legitimate response to capitalist oppression. Her lover, Alexander Berkman, served fourteen years in prison for attempting to assassinate the manager of the Carnegie Steel Mill during a bitter strike in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892. Goldman herself once horsewhipped a political opponent. But mostly Goldman used her great oratorical gifts to apply the lash. Although she was short, stout, and far from beautiful, Goldman was a powerful and charismatic speaker who thrilled her audiences with a vision of a new society in which there would be equality between the sexes as well as between the classes. Conservatives had longed to send “Red Emma” packing for years, and the Red Scare gave them their chance. As she was released from a prison term for opposing the war, Goldman was arrested again and held for deportation under the law passed following the McKinley assassination that banned advocacy of the overthrow of the government. The proceeding had been recommended by John Edgar Hoover, a twenty-four-year-old official of the Justice Department who was helping plan Palmer’s antiradical cam- paign. Hoover was listening intently as the government’s attorney made the case against Goldman during her deportation hearing.

In 1919, Russian-born feminist and anarchist Emma Goldman was deported from the United States. A prominent speaker, Goldman opposed the mass deportation of Russian immigrants. (Emma Goldman's deportation image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

If he hoped to hear Goldman plead for mercy, he was disappointed. She refused to speak during the hearing. Instead, in a statement that was read on her behalf by her attorney, Goldman attacked the effort to deport foreign radicals as an assault on free speech. “Ever since I have been in this country —and I have lived here practically all my life — it has been dinned into my ears that under the institutions of this alleged Democracy one is entirely free to think and feel as he pleases,” Goldman said.

"What becomes of this sacred guarantee of freedom of thought and conscience when persons are being persecuted and driven out for the very motives and purposes for which the pioneers who built up this country laid down their lives? ... Under the mask of the same Anti-Anarchist law every criticism of a corrupt administration, every attack on Government abuse, every manifestation of sympathy with the struggle of another country in the pangs of a new birth—in short, every free expression of untrammeled thought may be suppressed utterly, without even the semblance of an unprejudiced hearing or a fair trial."

Goldman warned that the government was making a terrible mistake by confusing conformity with security. “The free expression of the hopes and aspirations of a people is the greatest and only safety in a sane society,” she said. “In truth, it is such free expression and discussion alone that can point the most beneficial path for human progress and development.” Two months later, Hoover was standing on the dock as a decrepit government ship, the Buford, departed for Russia, carrying Goldman and 248 other deported radicals under heavy military guard. Goldman remained abroad until her body was returned for burial in 1940.

Free speech becomes increasingly controversial

While the government succeeded in silencing Goldman, the controversy over free speech continued to grow. Only weeks after Goldman’s hearing, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the most prominent member of the U.S. Supreme Court, indirectly endorsed her view that radical criticism of American institutions must be protected. This marked an important change in Holmes’s thinking. In March, he had written the decision upholding the imprisonment of Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party, for making a speech critical of America’s participation in World War I. But by November, Holmes had changed his mind. In a case involving the distribution of radical pamphlets, he urged his countrymen to recognize the importance of protecting free speech:

When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by a free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.

Holmes was unable to persuade his colleagues on the Supreme Court. Only Louis Brandeis joined his opinion. But an important turning point had been reached: free expression was no longer an issue for radicals alone; the fight for free speech had entered the political mainstream.

War and restrictions on freedom of speech

This was not the first time that freedom of speech had become a political issue. In 1798, when war with France appeared imminent, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts to punish French sympathizers. The Sedition Act provided a fine of up to $2,000 and two years in jail for anyone who published “any false, scandalous and malicious writing” about the U.S. government, Congress, or the president. Twenty-five people were prosecuted, and ten editors and printers were sent to jail. Opposition to the suppression of free speech was intense, and both laws soon expired. Between 1836 and 1844, northern abolitionists strenuously protested a gag rule that barred the House of Representatives from debating antislavery petitions. In 1863, the Union commander in Ohio imposed martial law and outlawed “declaring sympathies for the enemy.” A former Ohio congressman, Clement Vallandigham, was tried by a military commission and exiled to the Confederacy for violating the law. The arrest of Vallandigham was condemned as a violation of freedom of speech by Democratic newspapers throughout the North.

The first peacetime restriction on freedom of speech was passed in 1865 when Congress banned the mailing of obscene books and magazines. This law was broadened by Anthony Comstock in 1873 to ban advertisements for obscene material, which was also widened to include information about birth control. The passage of the Comstock Act did not generate the kinds of protests that had greeted the Alien and Sedition Acts or the arrest of Vallandigham. However, in 1902, a small group of radicals founded the Free Speech League to assert the First Amendment right of unpopular groups. Created in the aftermath of the assassination of President William McKinley by an anarchist in 1901, the Free Speech League opposed legislation restricting the right of anarchists to promote their views. It also came to the defense of those who were prosecuted under the Comstock Act for advocating free love and the use of birth control. But there was little sympathy for radicals, atheists, and advocates of open marriage. It took a world war to reveal that censorship threatened the rights of all Americans.

The assassination of President William McKinley by an anarchist, depicted above, led to proposed laws against anarchist speech. This led to the creation of the Free Speech League. (Public domain.)

Woodrow Wilson's worries about disloyalty increase

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the overwhelming majority of Americans believed that it had little to do with them. It seemed to concern only the territorial ambitions of countries that were an ocean away from the United States. The fact that modern weapons made the war unimaginably bloody — nearly one million men were killed and wounded in the Battle of Verdun alone — deepened the revulsion of the American people. Over the next three and a half years, however, America’s isolation eroded. German submarines attempted to strangle Great Britain by sinking any ship that might be carrying armaments. More than one thousand civilians, including one hundred Americans, lost their lives when a U-boat sunk the British liner Lusitania in 1915. In response to American demands, Germany agreed not to sink civilian ships without warning, but in January 1917 it announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. President Woodrow Wilson urged Congress to declare war in April. The war was about more than the freedom of the seas, Wilson said. In challenging the German autocracy, America was making the world “safe for democracy.” Later, he would propose a League of Nations, which he believed would eliminate the need for war. America would fight for nothing less than an end to all wars.

Many Americans remained unconvinced. There were deep divisions in the population. The growth of industry had produced vast wealth, but it was unevenly distributed, and the great mansions that graced New York’s Fifth Avenue were shadowed by slum districts where tuberculosis, alcoholism, and industrial accidents exacted a heavy toll. Many workers saw the clash of European powers as a capitalist struggle between countries attempting to extend their markets. The United States was also divided between immigrants and natives. Thirty million immigrants arrived between 1845 and 1915, and many of them had opinions on the war. The more than five million Germans included tens of thousands who still cherished memories of the fatherland, while not a few of the more than three million Irish immigrants hungered for the defeat of England.

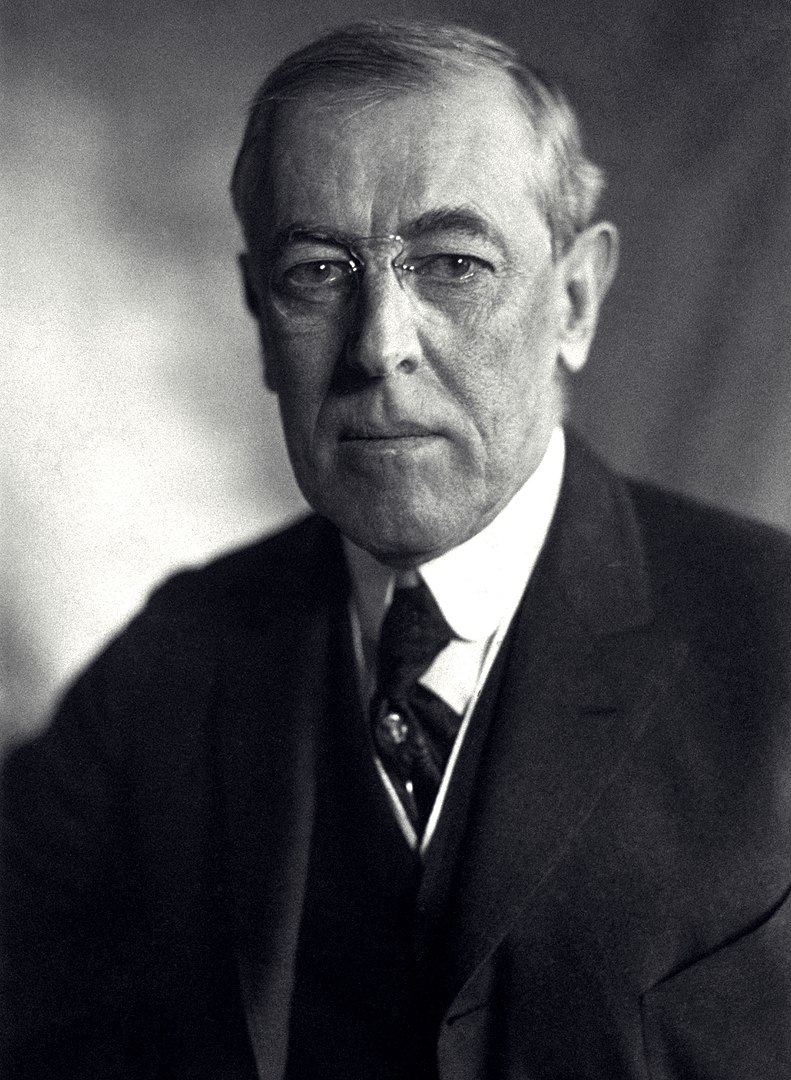

President Woodrow Wilson's suspicion of immigrants during World War I led to close government scrutiny of speech. (Photo of Woodrow Wilson, public domain, United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division)

President Wilson believed there was a serious threat of disloyalty, particularly among immigrants. As early as 1915, he told the Daughters of the American Revolution that he was looking forward to the time when disloyalty would be exposed. “I am in a hurry for an opportunity to have a line-up and let the men who are thinking first of other countries stand on one side and all those that are for America first, last, and all the time on the other,” he said. On December 7, Wilson’s annual message to Congress charged that the gravest threats against our national peace and safety have been uttered within our own borders.

There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed by our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life.

The next day, the members of Wilson’s cabinet agreed to cooperate more closely in their investigations of potentially disloyal groups and ordered the attorney general to draft legislation to curtail espionage and the right to express disloyal views. Although the legislation was introduced in June 1916, America was still at peace, and there was little support for drastic new measures. Once Congress declared war on April 6, 1917, however, the proposed “Espionage Act” moved to the top of the legislative agenda.

Espionage Act restricts press freedoms

America’s newspaper publishers were shocked by the proposed Espionage Act. It included a fine of up to $10,000 and a prison sentence of up to ten years for anyone who published information that would be useful or possibly useful to the enemy. The president himself would decide by proclamation whether the information fit the definition of the crime. The American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA) protested strongly that the provision would destroy freedom of the press, for the president could condemn any story as useful to the enemy, including criticism of his administration. Several influential senators agreed. “To attempt to deny to the press all legitimate criticism either of Congress or the Executive is going very dangerously too far,” Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts said. Wilson refused to back down. Press censorship was “absolutely necessary to public safety,” he told the New York Times. But weeks of hostile editorials finally persuaded the House to kill the provision.

The press censorship provision was only one of several that potentially affected free speech. The bill criminalized “willfully” making “false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces.” The punishment was a fine of up to $10,000 and twenty years in prison. This provision occasioned little controversy, perhaps because it seemed to threaten only enemy agents. But the Espionage Act also gave the post office broad new powers to exclude from the mails any material “advocating or urging treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance to any law of the United States.”

The post office begins censoring anti-war material

Leaders of the Free Speech League, who had seen how the post office abused its power under the Comstock Act, urged Congress to amend this provision. “I know what a tremendous instrument of tyranny this rather innocent looking provision of the bill will become,” a league attorney wrote Senator Robert La Follette of Minnesota. But no other organization expressed concern. The nation’s newspapers did not see either section as a threat to their interests, and they became law when the Espionage Act was passed in June.

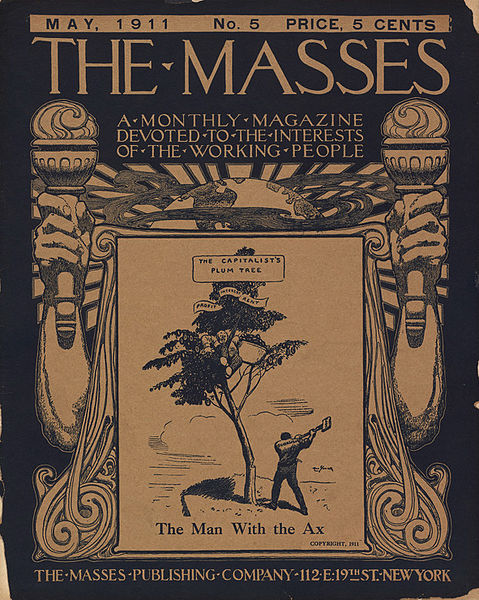

Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson immediately began using his new power to exclude from the mail any material that was critical of the war. In July, post office officials notified the editors of The Masses, a lively literary and political magazine with Socialist leanings, that they could not mail their Au- gust issue. When Max Eastman, the editor, demanded to know what articles violated the Espionage Act, the officials refused to tell him. A delegation of lawyers headed by the famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow traveled to Washington to urge the postmaster to establish clear standards so that editors would not inadvertently violate them. But Burleson, a Texan whose father had been a major in the Confederate army, was not impressed by a group of radical lawyers. The postmaster was one of the most powerful officials in the federal government because he controlled thousands of jobs. After more than a decade in Congress, Burleson knew his power and knew how to use it. He told his visitors a folksy story and sent them on their way.

The Masses, a socialist magazine, was one of many publications targeted by the U.S. Post Office during the Red Scare. (Front cover of The Masses May 1911, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The Masses finally forced the government to reveal the reasons for rejecting the August issue by challenging the post office in court. The truth was worse than anything they had imagined. The government lawyer pointed to four articles and four cartoons. The articles included a poem that eulogized Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, anarchists who had recently been arrested; an editorial that mentioned the arrests; another editorial about the importance of maintaining in-dividualism during a time of war; and a collection of letters from imprisoned conscientious objectors in Britain. One cartoon, “Conscription,” showed the evils of war. “War Plans” revealed a group of businessmen studying plans in a congressional meeting room, while members of Congress, watching from the sidelines, asked, “Where do we come in?” The post office also objected to a cartoon of a crumbling Liberty Bell.

Learned Hand's decision against the post office is overturned

U.S. District Court judge Learned Hand rejected the postmaster’s claim and ordered him to accept the magazine, but his decision was immediately stayed and later overridden by a federal appeals court. As a result, it was Burleson who decided what the American people could read during the war. In October, he felt confident enough to describe some of the things he was forbidding:

For instance, papers may not say that the Government is controlled by Wall Street or munitions manufacturers, or any other special interests.... We will not tolerate campaigns against conscription, enlistments, sale of securities [Liberty Bonds] or revenue collections. We will not permit the publication or circulation of anything hampering the war’s prosecution or attacking improperly our allies.

Socialist newspapers were the main target, and the post office banned at least one issue of twenty-two Socialist publications. Burleson successfully suppressed The Masses by arguing that it had ceased to be a “periodical” when its August issue was banned and had therefore forfeited the right to be distributed as second-class mail. The magazine hoped to save itself through newsstand sales but was forced to fold. The post office tried the same tactic against the Milwaukee Leader, a Socialist paper published by Victor Berger, a member of Congress. The post office even refused to deliver first-class mail to the Leader, a tactic that was occasionally employed against other “disloyal” parties, although it lacked any legal authority to do so. Postal authorities also threatened mainstream publications on occasion. After receiving a warning from the post office, The New Republic refused to carry an ad soliciting money to defend the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a radical labor union charged under the Espionage Act. The Nation had to appeal directly to President Wilson when the post office refused to accept an issue that was critical of Samuel Gompers, an administration supporter. Meanwhile, the foreign-language press generally abandoned any commentary on the war in order to win a license to publish under the Trading with the Enemies Act.

Prosecution under the Espionage Act

The Justice Department was also busy. In early September, its agents obtained search warrants for IWW offices all over the country. The IWW’s goal was to organize unskilled workers who were generally ignored by the unions that belonged to the American Federation of Labor. The “Wobblies” believed in a day when the power of organized labor would destroy capitalism, clearing the way for a more just social order. The Wobblies talked tough and were often engaged in violent conflicts with employers who would do anything to prevent their workers from organizing. (Their leader, “Big Bill” Haywood, was acquitted of charges that he had participated in the assassination of a former Idaho governor.) Like the Socialists who kept them at arm’s distance, the Wobblies opposed the war. But their goal was to create “one big union,” not to disrupt the war effort. Nevertheless, on September 26, 1917, federal agents rounded up 166 IWW leaders and charged them with violating the Espionage Act. They were indicted under the section that banned making false statements in an effort to disrupt the war effort. Nearly 100 were convicted, including Haywood, who was sentenced to twenty years by U.S. District Court judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. “When the country is at peace, it is a legal right of free speech to oppose going to war.... But when once war is declared, this right ceases,” declared Landis, who soon resigned to become the first commissioner of baseball, delivering the same stern justice to errant baseball players that he had shown the “reds.”

The prosecution of the Wobblies was the largest one carried out under the Espionage Act, but it was only the tip of the iceberg. Despite the best intentions of Attorney General Thomas W. Gregory, who was more sensitive to civil liberties concerns than Burleson, the Justice Department indicted 2,168 people under the Espionage Act and convicted 1,055. The victims included leaders of the Socialist Party like Rose Pastor Stokes, who was convicted for a letter to the editor of a St. Louis newspaper defending the right to dissent from the war. She was indicted for writing, “I am for the people and the government is for the profiteers.”

Eugene Debs giving a speech in Chicago in 1912. In 1918, Debs was jailed for a speech given in Canton, Ohio. He was convicted of obstructing military recruitment and enlistment. Sentenced to 10 years in prison, Debs appealed his conviction, arguing his speech was protected by the First Amendment. However, the Court upheld the conviction. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Eugene Debs, the four-time Socialist Party candidate for president, was sentenced to ten years for a speech he made in Canton, Ohio, in June 1918. Although Debs chose his words carefully, knowing that government stenographers were present at every speech, he was convicted for saying, “You need to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.” Debs served two and a half years in prison. In 1920, while serving his sentence, he ran for president for a fifth time and received over 900,000 votes. But his health was deteriorating. He died five years after his release at the age of seventy.

The overwhelming majority of prosecutions involved ordinary people. The country was in a war fever, and the Justice Department was under tremendous pressure to take action against every manifestation of disloyalty. This spirit of intolerance was encouraged by the government. “German agents are everywhere,” warned a magazine ad placed by the Committee on Public Information, a government agency. “Report the man who spreads pessimistic stories ... cries for peace or belittles our efforts to win the war.” Such propaganda was hardly necessary. Every day the newspapers published lists of dead and wounded Americans, and local officials of the Justice Department were flooded with reports of traitorous words. The son of a chief justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court was convicted for mailing a chain letter that asserted Germany had not broken its promise to end unrestricted submarine warfare. Thirty German Americans in South Dakota went to jail for sending a petition to the governor urging reforms in the draft laws. The producer of a film, The Spirit of 76, which depicted many patriotic scenes from the Revolutionary War, was sentenced to ten years in prison for including scenes portraying the atrocities committed by the British troops during the Wyoming Valley Massacre. “History is history, and fact is fact,” the judge acknowledged, but “this is no time” for portraying an American ally in a bad light. An Iowa man received a twenty-year term for circulating a petition urging the defeat of a congressman who had voted for conscription. Another Iowa man was sent to jail for a year for being present at a radical meeting, applauding and contributing twenty-five cents.

Support and protests

Many Americans believed the government needed their help in policing disloyalty. They joined dozens of private organizations that hunted spies, captured “slackers” who had not registered for the draft, and demanded that everyone purchase their fair share of Liberty Bonds. The American Protective League had 250,000 members who carried badges that said they were members of the “Secret Service.” Attorney General Gregory explained that their job was “keeping an eye on disloyal individuals and making reports of disloyal utterances.” In practice, they acted as vigilantes, pulling people off the street for questioning and searching homes without warrants. Whether acting through organized groups, in mobs formed at the spur of the moment, or as outraged individuals, the patriots often used violence against their enemies. Mobs tarred and feathered those they thought to be disloyal, many of whom were German. Charles Klinge was beaten and forced to kiss the flag in Salisbury, Pennsylvania, for remarks he had made about the war; George Koetzer was tarred and feathered and tied to a brass cannon in a park in San Jose, California. Robert Prager, a German immigrant and Socialist, was lynched by a group of drunken miners in Collinsville, Illinois.

Protests against violations of civil liberties began within weeks of America’s entry into the war. At first, the critics hoped they would be able to make some headway through direct appeals to the administration. Lillian Wald, a pioneering social worker who had founded the Henry Street settlement house in New York, knew Woodrow Wilson personally. Less than two weeks after Congress declared war, she wrote the president that free speech was already under heavy assault: “Halls have been refused for public discussion, meetings have been broken up; speakers have been arrested and censorship exercised, not to prevent the transmission of information to enemy countries, but to prevent the free discussion by American citizens of our own problems and policies.”

Over the next eighteen months, there would be frequent appeals to Wilson and other members of the administration. Like Wald, the protesters were liberals who often knew Wilson or other highly placed government officials, in- cluding the leaders of the War Department and the Justice Department. But the president and his assistants were charged with winning the war and responsible for enforcing the Espionage Act and the other repressive measures passed by Congress. While frequently acknowledging their own concern about the violation of the right of free speech, there was little they could do to help.

Wald could do more than write letters to the president, however. She was the chair of one of the largest peace groups in the country, the American Union Against Militarism (AUAM). The AUAM had been founded in 1915 in an effort to prevent the United States from being drawn into the war. Now that war had come and Congress had instituted a military draft, it was assisting the growing number of conscientious objectors who were refusing to fight. Most of these men were Quakers and Mennonites, who were inducted despite the fact that their religions opposed violence. Religious scruples did not impress military officers, and conscientious objectors were imprisoned and subjected to harsh punishments in an effort to force them to fight. In April 1917, the AUAM had welcomed a new staff member, Roger Baldwin, a young man from Massachusetts who had made a name for himself as a reformer in St. Louis. Baldwin immediately threw himself into the task of negotiating fair treatment for the conscientious objectors. Two weeks after the passage of the Espionage Act, the AUAM put Baldwin in charge of the new Civil Liberties Bureau (CLB) to act as a clearinghouse for information about the rights of war resisters. However, the CLB’s mandate soon grew to include challenges to free speech.

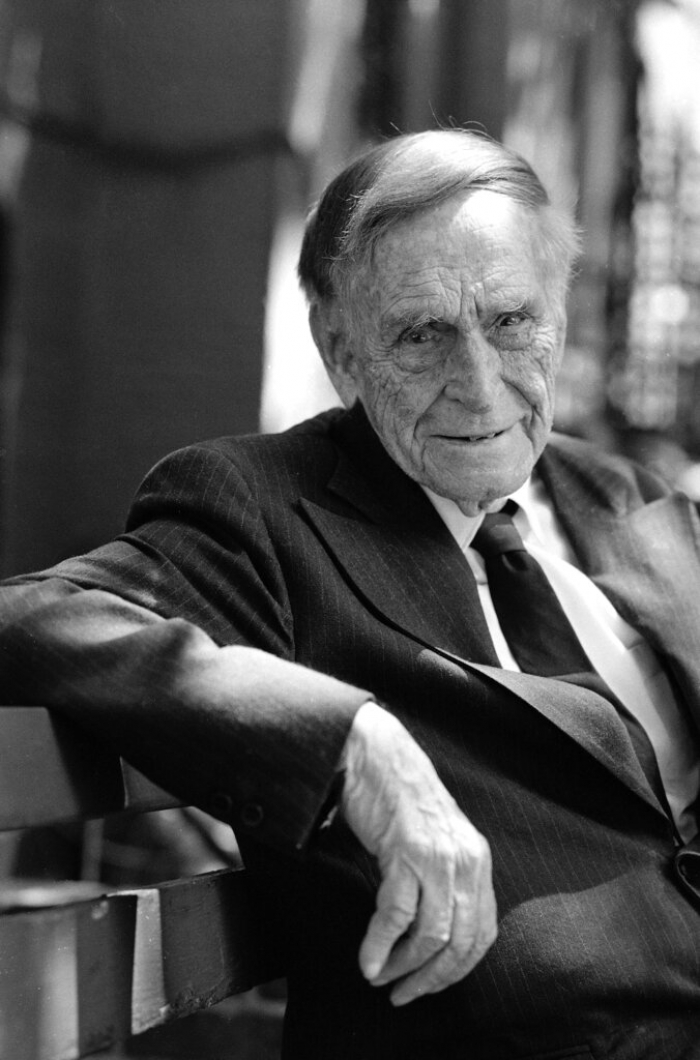

Roger Baldwin, founder of the ACLU, is pictured at home in New York’s Greenwich Village, June 1978. (AP Photo/Jerry Mosey)

Roger Baldwin's start with the American Union Against Militarism

The thirty-three-year-old Baldwin was well suited for his new job. Born in Wellesley Hills, a suburb of Boston, he had grown up in a family with enough wealth to free him from any concern about making a living. It was also a family that encouraged free thinking. Wellesley Hills was only fifteen miles from Concord, the home of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, who were the foremost advocates of the view that the individual conscience was superior to organized religion and every other institution in determining truth. “I was aware of Emerson, Thoreau and the Alcotts about as soon as I was aware of any intellectual figures,” Baldwin said. “They were household names.” Not all Baldwins admired individualism. One of Roger’s great-uncles who lived in Lexington, Massachusetts, shocked the boy by calling Thoreau “that loafer.” But Roger’s father, Frank, a leather merchant who owned several factories, was a fan of Robert G. Ingersoll, a renowned lecturer who called himself “the great agnostic.” Not surprisingly, Roger hoped to emulate men who had defied convention. “I sought character, personality, uniqueness,” he said.

The Baldwins’ individualism was disciplined by a strong social conscience. Roger attributed this to Unitarianism. “Doing other people good seemed the essence of Unitarianism,” he said. As a boy, he participated in church projects raising money for a hospital ship and gathered wildflowers for the sick in Boston hospitals. “The Unitarian Church was my social center,” he explained. Several of Roger’s relatives were deeply involved in movements for reform. His grandfather William H. Baldwin had established the Young Men’s Christian Union in Boston in 1870 to provide adult education, recreation, and other social services. His uncle William H. Baldwin Jr. was the president of the Long Island Rail Road, but he was also the chairman of the Committee of 14, a group that was fighting widespread prostitution in New York City. He served as president of the New York City Club and as director of the National Child Labor Committee. His uncle’s wife, Ruth, was a Socialist and a founder of the National Urban League.

Roger Baldwin arrives in St. Louis

Roger’s reform proclivities first announced themselves when he was a student at Harvard College. He was soon teaching at the Cambridge Social Union, which offered adult education classes for workers, and he later organized the Harvard Entertainment Troupes to provide entertainment to Boston’s settlement houses. At the end of college, Roger sought career guidance from a family friend, the prominent attorney Louis Brandeis. Brandeis had become known as the “people’s attorney” because of his willingness to challenge the corruption fostered by streetcar franchises and misconduct in the insurance industry. Brandeis urged Baldwin to devote his life to public service. He also told the young man to get out of town. “Leave Boston,” he said. “I started my career in St. Louis, and I don’t regret it—it’s the center of democracy in the United States.” Baldwin packed his bags.

Louis Brandeis encouraged Baldwin to get his start in St. Louis. (Photo by Harris and Ewing, public domain via the Library of Congress)

He arrived in St. Louis in 1906, at the high tide of the period that became known as the Progressive Era. The issue of reform had moved to center stage in response to the crusading journalism of reporters who became known as “muckrakers” for their willingness to criticize the pioneering capitalists who had been widely hailed as the paragons of American civilization. The muckrakers revealed to a horrified nation that the rapidly expanding corporations had grown as a result of ruthless tactics used to suppress competition and the corruption of elected officials whose duty it was to protect the public interest. The outrage had helped generate a movement to expand the power of government to regulate business and to solve the many problems created by unrestrained industrialism and the rapid growth of urban areas. Although the “Progressive movement” appeared to have sprung into existence almost overnight in the first years of the new century, reformers had been hard at work for many years. A new profession of social work had been organized to meet the needs of people who lived in dire poverty in the nation’s cities. When government refused to address the problems of the nation’s slums, social workers created privately run settlement houses to offer people help in adjusting to urban life.

For Baldwin, public service meant social work. His aunt Ruth was overjoyed by his decision. (Even his father had welcomed the news, which surprised him.) She immediately arranged introductions to some of the leading social workers of the day, including Lillian Wald. Baldwin also met Jacob Riis, the former police reporter whose 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives, had shocked the nation’s conscience, and Owen Lovejoy, head of the National Child Labor Committee, which was fighting the employment of children in factories. The reformers embraced the twenty-two-year-old Baldwin. E. M. Grossman, a St. Louis lawyer who was also a Harvard alumnus, was looking for someone to head a settlement house as well as to establish a department of sociology at Washington University. One of Baldwin’s professors had recommended him to Grossman on the basis of his work at the Cambridge Social Union. Baldwin had never taken a single course in sociology, but he gladly accepted the job offers and set off for St. Louis “full of enthusiasm, ignorance and self-assurance.”

Organizing and reform in St. Louis

Roger Baldwin never lacked self-assurance. He was the oldest child of one of the country’s oldest families. As the proprietor of his own business, Frank Baldwin was used to being in charge and ruled his seven children firmly. But in a house where unorthodox ideas were welcome, there was room for self-expression. Roger also received reinforcement from social relationships that he developed with adults far more easily than with other children of his age. Several of his teachers became close friends. Combined with a social status that gave him access to the “best families,” Baldwin’s strong confidence in himself and his abilities was irresistible. He took on the challenge of two jobs about which he knew little without a second thought.

His willingness to accept new challenges served him well in St. Louis. The Gateway City had not always been “the capital of democracy.” It had been ridiculed by one of the nation’s leading muckrakers, Lincoln Steffens, in a 1902 article, “Tweed Days in St. Louis.” But Steffens’s article had helped to launch a municipal reform wave that had made significant progress by the time of Baldwin’s arrival. There may have been no better city in the world for a talented young man looking to make a name for himself as a reformer. Just a year after his arrival, in 1907, the judge who headed the city’s new juvenile court offered Baldwin the chance to become the court’s first chief probation officer. The movement to treat juvenile crime differently from adult crime was one of the most important initiatives of the Progressive Era, and Baldwin eagerly accepted a role in it. To meet the challenge of overseeing the rehabilitation of two thousand children, Baldwin assembled a staff of fifteen probation officers, most of whom were older than he was. Some members of the state legislature thought he was too young to handle so much responsibility and passed a law setting twenty-five as the minimum age of a probation officer. However, the law did not affect Baldwin, who had just turned twenty-five.

In 1907, St. Louis was a hot spot for political and social reform. (Public domain.)

Baldwin’s talent for organizing developed quickly in his new job. The year after he became a probation officer, he helped establish the National Probation Officers Association. In St. Louis, he created the Social Service Conference for social workers, the Council of Social Agencies, and an association of neighborhood civic groups. Baldwin was also a key player in the organization of the first group of St. Louis social workers to enroll both whites and African Americans. Baldwin possessed enormous energy and displayed a willingness to turn every social occasion into an opportunity to advance his cause. It didn’t hurt that he was also attractive. “Tall, wiry, handsome and vigorous,” he was one of the city’s most eligible bachelors and was invited to all the important social events. Baldwin was also on the rise professionally. In 1910, he left the juvenile court to become the leader of the St. Louis Civic League, a leading reform group, where he led the fight for the reform of municipal government.

But the new job did not halt a growing dissatisfaction with the reform movement. Baldwin began to believe that the problems created by industrial society ran deeper than the measures that reformers were pursuing to correct them. Social workers and probation officers attempted to help people without recommending any way to eliminate the poverty that was the source of their problems. Many liberals came to believe that capitalism itself would have to be eliminated.

But Baldwin was not attracted to socialism. Socialists were obsessed “with a scheme of salvation.” They were “too doctrinaire, too German and too old,” he said. Indeed, he was skeptical of all radicals until he was dragged by friends to hear a speech by Emma Goldman. The speech was a revelation. “Here was a vision of the end of poverty and injustice by free association of those who worked, by the abolition of privilege, and by the organized power of the exploited,” Baldwin recalled many years later. Baldwin was particularly attracted by Goldman’s exposition of anarchism. His native belief in individualism responded strongly to the demand for the abolition of government and the free development of the potential of every man. He arranged to meet “Red Emma” and helped organize several speaking engagements for her.

Baldwin and Radicalism

Baldwin would never lose his attraction to radicalism. He had been raised to care about those who were less fortunate than him. “I was for the underdog, whoever he was, by training and instinct, and I had an endless capacity for indignation at injustice,” Baldwin told an interviewer fifty years later. “Any challenge to freedom aroused me and I was not satisfied until I acted.” It was this passion that led the respectable leader of the St. Louis Civic League to provide bail for Wobblies who had been jailed for refusing to pay for their meals in local restaurants. (They told the owners to bill the mayor.) It also prompted him to take up his first free speech case. When Margaret Sanger, the birth control advocate, was barred from speaking at a private hall, Baldwin persuaded her to present her address on the steps of the building. With a large contingent of police standing by, Baldwin introduced Sanger, who proceeded to give her speech. Baldwin was driven not just by his sympathy for the underdog. He believed that it was people like Emma Goldman and Margaret Sanger who moved humanity forward. “I am dead certain that human progress depends on those heretics, rebels and dreamers ... whose ‘holy discontent’ has challenged established authority and created the expanding visions mankind may yet realize,” Baldwin said.

Margaret Sanger, an advocate for birth control, was one of many speakers harmed by the extensive press restrictions of the late 1910s. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

One reason that Baldwin admired radicals so much was that he knew he could not do what they did. Some could plunge themselves into the proletarian movement, cutting their ties to family and friends. While Baldwin would later pose as a working man to experience industrial life directly, he could never permanently “unclass” himself. He acknowledged that he felt guilt about this. Yet there was more involved than an unwillingness to deprive himself of the comforts of an independent income. Baldwin felt a strong sense of responsibility to the organizations that he worked for. “I have long had the failing, if it is that, of accepting the philosophy of the lesser evil up to the point of a clear collision with principles I couldn’t surrender,” he said. Roger Baldwin was not a prophet. He was an idealist who gave up the promise of utopia for incremental gains in social justice. He was the perfect man to lead the fight for free speech.

Baldwin embarked on his civil liberties career in April 1917. A pacifist, he had been appalled by the country’s rapid transformation from a nation “too proud to fight” to one that was preparing to fight the war “to end all wars.” Although he was active in the peace movement in St. Louis, he was impatient to join a national organization. He volunteered his services to Crystal Eastman, the executive secretary of the AUAM. “How and where in your judgment could you use me?” he asked in a letter. He also said he would work for free. A short while later, he arrived in New York. Although America’s entry into the war seemed inevitable by then, there was still important work to do. After Congress passed a conscription act in May, thousands of pacifists found themselves in dire need of help. The Selective Service Act exempted from military service only members of the three “historic peace churches” (the Quakers, the Mennonites, and the Brethren). Other pacifists were being inducted and sent to military training camps, where they were beaten and jailed in an effort to force them to fight. The AUAM was soon being bombarded with requests for legal advice. In addition to pleas from the men who were already in the military, it counseled those who hoped to win exemption. AUAM lawyers took on the cases of hundreds of men every week.

Baldwin brought to his new job all of the energy and self-confidence that had been his trademark in St. Louis. He felt sure that he would be able to influence high Washington officials. Many of them were wellborn like him, and not a few were former Harvard classmates. The Wilson administration also included men like Secretary of War Newton Baker, who had been leaders in the reform movement. Baldwin assumed that he shared certain values with these officials: certainly, no one wanted to see conscientious objectors abused, and everyone agreed on the importance of free speech. He did everything he could to assure them that he wanted to cooperate with the government in re- solving the problems created by the draft. “We don’t want to make a move without consulting you,” Baldwin wrote to Frederick D. Keppel, the assistant secretary of war. Above all, Baldwin was confident in his own considerable skill at public relations. He recognized that in a time of war government critics had to be particularly careful to present themselves as loyal to the nation’s traditions. To an organizer of an antiwar rally, Baldwin recommended: “We want also to look like patriots in everything we do. We want to get a good lot of flags, talk a good deal about the Constitution and what our forefathers wanted to make of this country, and to show that we are really the folks that really stand for the spirit of our institutions.” Baldwin was certain that breeding, contacts, and public relations would go a long way toward minimizing wartime repression.

The creation of the Civil Liberties Bureau

His confidence was entirely misplaced. He did indeed enjoy extraordinary access to high officials of the Wilson administration. He met with the secretary of war himself in June and kept up a regular correspondence with his assistant, Keppel. But once war had been declared, the Wilson administration became entirely focused on winning, and everyone who wasn’t loudly prowar was suspected of disloyalty. The AUAM and other pacifist organizations inevitably came under suspicion for their defense of conscientious objectors. In May, Baldwin had called together the representatives of other pacifist groups and created the Bureau for Conscientious Objectors (BCO), which operated as a division of the AUAM. Although Baldwin strongly denied it, many government officials suspected that the purpose of the BCO was not to defend the rights of the conscientious objectors but to obstruct the draft, which was now a crime. Justice Department agents visited the AUAM office in Washington on more than one occasion as part of an inquiry into its loyalty. Although the organization was told that its activities “would not be interfered with,” the Washington Post reported in June 1917 that the AUAM was under government surveillance.

Lillian Wald and Paul U. Kellogg, the cochairs of the AUAM, were alarmed that they might have come under suspicion of disloyalty. “We cannot plan continuance of our program which entails friendly government relations ... and at the same time drift into being a party of opposition to the government,” Wald warned. She wanted the Bureau for Conscientious Objectors to be removed from the AUAM. Bald- win objected. “Having created conscientious objectors to war, we ought to stand by them,” he said. A majority of the board supported Baldwin. To placate Wald, however, they re- named Baldwin’s project the Civil Liberties Bureau in the hope that this would make it more acceptable to the government. Crystal Eastman, who proposed the compromise, argued that no one would deny the importance of protecting the civil liberties of all Americans. Baldwin opened the new Civil Liberties Bureau on July 2, just two weeks after the passage of the Espionage Act.

The Civil Liberties Bureau reflected the pacifist background from which it had emerged. Its directing committee was made up largely of men and women who opposed war for religious reasons. Its chairman was a Quaker lawyer, L. Hollingsworth Wood, and the committee included several clergymen, Norman Thomas, a Presbyterian; John Haynes Holmes, a Unitarian; and Judah L. Magnes, a rabbi. The first concern of the religious members was the treatment of the conscientious objectors who were suffering for their religious beliefs. However, the committee also included two social workers, Baldwin and Eastman, and was soon joined by two lawyers, Walter Nelles and Albert DeSilver, who would quit their successful practices to devote themselves to civil liberties work. The committee held long meetings over lunch at the Civic Club on West Twelfth Street every Monday. As the weather grew hotter, the meetings were adjourned to a picnic table in the club courtyard. There the committee members reviewed the growing list of cases involving the violation of civil liberties. In addition to news of the mistreatment of conscientious objectors, every week brought new reports of mob violence against Socialists, immigrants, and others suspected of being disloyal. There were also a growing number of acts of suppression by government. Meeting permits were denied to critics of the war, and meetings that did occur were often broken up by the police or with their connivance. Prosecutions under the Espionage Act were also increasing rapidly. There wasn’t much the Civil Liberties Bureau could do about mob violence, but it worked hard to make Americans see the importance of civil liberties. It issued a pamphlet written by Norman Thomas, War’s Heretics, which attempted to win sympathy for conscientious objectors by stressing the importance of liberty of conscience. The Civil Liberties Bureau also assisted the victims. At a time when most lawyers were refusing to take on the cases of people challenged under the Espionage Act, the Civil Liberties Bureau compiled a list of cooperating attorneys who would help them. It also solicited contributions to help clients make bail and pay for their defense. “We make no distinction as to whose liberties we aid in defending, except that we do not handle any cases of enemy aliens, spies or draft dodgers,” the Civil Liberties Bureau explained in an early publication.

But the launching of the Civil Liberties Bureau did not succeed in removing suspicion of the AUAM. Doubts about its loyalty grew in August when the AUAM agreed to send delegates to a “peace” convention sponsored by the People’s Council of America for Democracy and Peace, a coalition of radical groups. This decision prompted the resignation of Lillian Wald as cochair of the organization. In one last effort to placate her and other social workers in the group, the AUAM board agreed to cut its ties to the Civil Liberties Bureau. On October 1, the Civil Liberties Bureau became a separate organization, the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB).

Trouble with the National Civil Liberties Bureau

The founding of the NCLB gave Baldwin the freedom to pursue more aggressive efforts to dramatize the widespread violation of civil liberties, but he quickly discovered that he could not count on the support of many liberals. He wanted to dramatize the problem of mob violence, and he thought he had found the perfect case in late October when the Reverend Herbert Bigelow, a Cincinnati pacifist, was kidnapped, whipped, and ordered to get out of town. Bigelow was a prominent Progressive reformer, and President Wilson himself condemned the attack. Baldwin attempted to organize a protest meeting in New York, but the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and other liberal groups refused to participate. Historian Charles A. Beard feared the meeting would be more “an anti-war than a pro-liberty meeting.” William English Walling, a prowar Socialist, believed the purpose of the meeting was “not the protection of free speech but the propaganda of an immediate or German-made peace.” Charles Edward Russell, another Socialist, condemned it as “anti-American and anti-democratic.”

The program, American Liberties in Wartime, was held anyway and drew a large crowd to the Liberty Theater. It received extensive and sympathetic coverage in New York’s Socialist newspaper, The Call. The audience listened breathlessly as Bigelow described his kidnapping. “The murderers!” a man shouted when Bigelow paused. Norman Thomas, a member of the NCLB board who would succeed Debs as the nation’s most prominent Socialist leader, demanded an investigation into the treatment of conscientious objectors in military camps. It was left to Dr. Joseph McAfee to address the free expression issue raised by the Bigelow case. “It is supremely important that the American people have the right to think,” McAfee said. “There was never so much need as now of sturdy thinking, clear thinking, unhampered thinking.... We demand that the government of the United States be buttressed by the free public discussion of every issue.” But good coverage in a Socialist newspaper would not influence many Americans. The brief article in the New York Times sent a more powerful message. “Most of the people present apparently were in hearty disagreement with the Government’s ban on seditious criticism of the war,” the reporter wrote. One of the speakers was Lincoln Steffens, the most famous of the muckraking journalists who had helped launch the Progressive movement. Steffens had grown dissatisfied with reform, however, and had come to believe that capitalism was the root of the country’s troubles. He also believed that capitalism had caused the war, a conviction he shared with the audience at the Liberty Theater. To the Times reporter, this remark and the reaction to it confirmed the disloyalty of both the speaker and the audience. “It cheered to the echo a remark ... by Lincoln Steffens, who declared that the ‘Kaiser did not start the war.’ ” Baldwin abandoned the idea of holding any more public programs during the war.

The NCLB soon lost any chance of capturing public approval. When the leaders of the IWW were brought to trial in April, NCLB published a pamphlet called The Truth about the IWW, which defended the radical group as a legitimate labor organization and rejected the charges of sedition that had been filed against its leaders. Baldwin had worked hard on the report, and historians would later uphold his argument that the IWW had never constituted a revolutionary threat. But Americans believed their government as the prosecutors laid out their case. Meanwhile, other federal officials were outraged that the NCLB would defend an organization that was obviously bent on the country’s destruction. The government had had mixed feelings about Baldwin and his civil libertarians. Some officials considered them outright traitors, but their high-level contacts with others in the Wilson administration prevented the foes of the NCLB from taking action. For his part, Baldwin was doing everything he could to allay the concerns of his government friends. Conceding that the NCLB may have inadvertently crossed the now vague line between legal and illegal conduct, Baldwin assured Keppel of the War Department, “We are entirely willing to discontinue any [illegal] practices.” He went even further, sending the Justice Department the names of financial contributors, cooperating attorneys, and the people on the NCLB mailing list, exposing all of them to potential prosecution if the NCLB was ever declared in violation of the Espionage Act. Such a disclosure would undoubtedly have led to outraged protests if the NCLB’s supporters had been aware of it. But the issue soon became moot. On August 31, the FBI raided the NCLB headquarters at 70 Fifth Avenue, seizing all its records.

FBI raid devastates the National Civil Liberties Bureau

Baldwin was shocked. Obviously, he would not have volunteered the NCLB records if he thought there was any possibility that they might be used against the organization and its supporters. His view had always been that the NCLB and the government had a common interest in protecting individual rights. Suddenly, the NCLB was confronting agents who were under orders to find anything that “either directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously, might tend to hinder winning the war, especially letters to or from anarchists, socialists, IWW’s or any other God-damn fools.” Walter Nelles, one of the NCLB attorneys, rejected the search warrant handed to him by agent R. H. Finch, telling him the warrant was not in proper legal form. Finch replied by drawing his gun and ordering Nelles to stand aside. Nelles then called Baldwin, who arrived in a highly excited state. He “told us that he ‘did not give a damn about anything—go ahead, lock him up, shoot him, hang him or anything else,’ ” Finch reported. Nelles later described the scene to the directing committee, emphasizing the humor in it. “It was all Gilbert-and-Sullivanesque, and no one on our committee was greatly alarmed,” Lucille Milner, a committee member, recalled later.

But the situation of the NCLB was no laughing matter. Only two weeks before the raid, the post office had notified Baldwin that it was banning fourteen of his pamphlets. A post office lawyer acknowledged privately to the Justice Department that the pamphlets did not violate the Espionage Act but insisted that defending the IWW did. Therefore, all NCLB activities were illegal. To make matters worse, the NCLB was about to lose its leader. In August, Congress had expanded the draft to include men between the ages of thirty and forty-five. Baldwin was thirty-four, and the signs of his impending conscription were everywhere. In early September, the American Protective League (APL) had launched a nationwide hunt for men of military age who had not registered for the draft. The largest “slacker” raid detained more than twenty thousand young men in Manhattan. The APL men were searching the streets when Baldwin wrote a letter notifying the draft board that he would not report for a physical:

I am opposed to the use of force to accomplish any end, however good. I am therefore op- posed to participation in this or any other war. My opposition is not only to direct military service, but to any service whatsoever designed to help prosecute the war. I am furthermore opposed to the principle of conscription in time of war or peace, for any purpose whatever. I will decline to perform any service under compulsion regardless of its character.

Baldwin asked for no favors except a speedy trial. He would refuse bail and share the fate of the indigent draft resisters who could not afford to post bond. He intended to plead guilty and expected to be sentenced to a year in jail. The government investigation of the NCLB raised the prospect that the members of the directing committee would join Baldwin in jail. One director urged the organization to reduce its activities at least temporarily and thus avoid doing anything to “otherwise aggravate the situation.” The other members of the committee were also worried about being indicted, but they were more concerned that Baldwin might be the only one charged with violating the Espionage Act. “If they indict some and not all, I shall be greatly disappointed,” Albert DeSilver wrote to his wife. “’Taint fair any other way because we are all equally responsible.” Instead of retreating, they decided to counterattack. The NCLB had already filed a lawsuit challenging the post office’s ban on its publications. The committee agreed to press ahead with its case and to file a new one in an effort to force the government to return its records. The committee members also agreed to intensify their efforts to draw press attention to their activities to make it as difficult as possible for the government to prosecute them. At the same time, to represent them in their dealings with the government, they hired attorney George Gordon Battle, a conservative southerner who had good connections with Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine that ran New York City.

The strategy worked. The official who was leading the investigation, U.S. Attorney Francis G. Caffey of New York, told the attorney general that the NCLB could be indicted for many of its activities, including its defense of men who had been convicted for sedition. But other Justice Department officials urged caution. “As the avowed purpose at least of this Bureau is the protection of civil liberties ... it is of the first [importance] that no action be taken by arrest, suppression or otherwise unless it be based upon facts showing a violation of the express provisions of the law,” John Lord O’Brian, an assistant to the attorney general, wrote Caffey. After reading Caffey’s final report, O’Brian concluded that the NCLB had not violated the law. “The organization of defense of persons accused of a crime” is not “in and of itself a crime,” he said. The Justice Department also indicated at this time that it had no objection to the mailing of NCLB pamphlets, a move that cleared the way for a judge to order the post office to resume their delivery. These decisions, coming on the eve of the signing of the armistice in November 1918, were the first significant free speech victories during World War I. With the end of the war, the civil libertarians looked forward to an easing of repression, but things were about to get rapidly worse. Instead, the fear of communism began to grip the country. As the Red Scare got under way, they searched desperately for someone to stand up for individual rights. The one place that they were sure they would never find help was the courts.

The courts fail to protect free speech

The American courts had played an abysmal role in protecting free speech since 1917. Swayed by their own strong support for the war, judges sent more than one thousand people to jail. They argued that the First Amendment barred censorship of written speech only prior to its publication. Once a book or pamphlet had been published, the government could punish its author if it was socially harmful. This test of whether speech had a “bad tendency” became the major benchmark in Espionage Act cases. When the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the conviction of a man whose book criticized the war but did not directly advocate illegal acts, it explained:

It is true that disapproval of the war and the advocacy of peace are not crimes under the Espionage Act; but the question here ... is whether the nature and probable tendency and effect of the words ... are such as are calculated to produce the result condemned by the statute.... Printed matter may tend to obstruct the ... service even if it contains no mention of recruiting or enlistment. The service may be obstructed by attacking the justice of the cause for which the war is waged, and by undermining the spirit of loyalty which inspires men to enlist or to register for conscription in the service of their country.

The question of what the effect of antiwar speech would be was to be left to the jury to decide. But in the absence of a requirement that speech directly advocate illegal acts, it was clear how jurors, whose sons were fighting in France, would vote. In retrospect, it is remarkable that they didn’t convict everyone charged under the Espionage Act.

The Supreme Court ruled in several important cases limiting free speech during the White Court era (1910-1921). Pictured is the Supreme Court c. 1916. Standing, L-R: Louis Dembitz Brandeis, Mahlon Pitney, James Clark McReynolds, John Hessin Clarke. Seated, L-R: William Rufus Day, Joseph McKenna, Edward Douglass White, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Willis Van Devanter. (Photo via Library of Congress, public domain)

The U.S. Supreme Court had the power to reverse these decisions. But when the first Espionage Act cases finally arrived on appeal in March 1919, the Court gutted the First Amendment. In three cases, it endorsed the use of the bad tendency test during wartime and upheld long jail sentences for opponents of the war who had urged people to exercise their democratic rights. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the opinions in all three cases for a unanimous court. A veteran of the Civil War, the seventy-seven-year-old Holmes, who sported a luxuriant, white handlebar mustache, was the oldest justice. Despite his age, he was known to possess one of the best legal minds on the Court. In 1905, he had rejected the deep conservatism of his colleagues by voting to uphold a pioneering New York statute that limited the labor of bakery workers to ten hours per day. It was in part because Holmes was the Court’s most distinguished justice that his opinions in the Espionage Act cases were so disappointing to civil libertarians. In the first one, Schenck v. United States, Holmes observed that the First Amendment’s protection of the right of free speech was obviously not absolute. “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater, and causing a panic,” he wrote. There were additional limitations in wartime. Congress had passed the Espionage Act to protect the government’s ability to successfully prosecute the war. It had a right to limit words that posed “a clear and present danger” of disrupting the war effort. A week after deciding the Schenck case, the Supreme Court handed down similar rulings in Frohwerk v. U.S. and Debs v. U.S., making it clear that the government was free to suppress dissident speech during wartime.

But the issue of free speech during wartime was being rapidly eclipsed by new threats to First Amendment rights. As the fear of communism grew during 1919, many voices were raised to demand a continuation of the censorship of the war years. Rioting had broken out in several cities on May 1 when workers gathered to celebrate May Day, an international holiday for labor. Although most of the rioting was started by ex-soldiers and other “patriotic” citizens, many state legislatures responded by banning the display of red flags, which they saw as a symbol of revolution. Politicians also called for the suppression of radical speech. Oregon and Oklahoma passed laws that made it a crime to advocate unlawful acts “as a means of accomplishing ... industrial or political ends, or ... industrial or political revolution, or for profit.” The mayor of New York wanted to ban meetings that tended “to incite the minds of people to a proposition likely to breed a disregard of the law,” and the mayor of Toledo, Ohio, prohibited any meeting anywhere in the city “where it is suspected a man of radical tendencies will speak.” In Washington, Congress was giving serious consideration to a bill providing ten years’ imprisonment for anyone who encouraged resistance to the United States, defied or disregarded the Constitution or laws of the United States, or advocated any change in the form of government except in a manner provided for by the Constitution. Under the bill, almost any protest against government could be treated as a federal crime.

Advocates of free speech continue to emerge

Yet, even as the Red Scare grew, there were signs of a new awareness of the importance of free speech, particularly among lawyers. In fact, the legal profession had never been unanimous in its view of the Espionage Act. In the first months of the war, U.S. District Court judge Learned Hand had ordered the post office to resume the delivery of The Masses. Hand conceded that the magazine’s antiwar articles and cartoons might well undermine support for the war, even causing men to resist the draft. “Political agitation ... may stimulate men to the violation of the law,” he wrote in his decision. However, nothing in the magazine expressly urged illegal acts. There is a difference between political advocacy, which is a safeguard of free government, and violent resistance, which undermines government. This “distinction ... is not a scholastic subterfuge, but a hard-bought acquisition in the fight for freedom,” Hand said. Six months later, George Bourquin, a federal judge in Montana, also refused to punish antiwar speech. The government had indicted Ves Hall for saying that Germany would “whip” the United States and that “the United States was only fighting for Wall Street millionaires.” Bourquin ordered the jury to acquit Hall because his remarks were clearly statements of opinion, not an attempt to cause insubordination in the armed forces. The Espionage Act was not intended “to suppress criticism or denunciation, truth or slander, oratory or gossip, argument or loose talk,” he declared.

Hand and Bourquin paid a price for their independence. Hand’s decision was quickly appealed and reversed, and he was passed over for promotion when the next opening occurred on the appeals court. Bourquin’s ruling led to howls of protest locally where mine operators were eager to use the federal government to suppress the Wobblies. There were calls for Bourquin’s impeachment and removal from office, and the governor convened a special session of the legislature to pass a law that would suppress the speech of people like Ves Hall. Many in Congress were also outraged, and at the suggestion of the Justice Department an amendment to the Espionage Act was passed in May. The Sedition Act made it a crime to speak, print, or write “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language ... as regards the form of government of the United States.

If a few judges could not hold back the wave of suppression, however, their defense of free expression inspired others to question the legal arguments that were being used to suppress the antiwar movement. There were at least a handful of lawyers who were willing to challenge the status quo. In addition to NCLB board members Walter Nelles and Albert DeSilver, there were those who answered the NCLB’s call for “cooperating attorneys” who were willing to take on the highly unpopular task of defending antiwar protesters. A number of law school professors were also sympathetic. In the summer of 1918, a thirty-two-year-old professor at Harvard Law School began a systematic study of the use of the Espionage Act to suppress political speech. Zechariah D. Chafee Jr. was a very unlikely candidate to emerge as the champion of the First Amendment rights of Socialists, Wobblies, and other radicals. Born in Providence, his father was a wealthy iron manufacturer, and his mother was a descendant of Roger Williams, the founder of the Rhode Island colony. “My family is a family that has money,” Chafee would say later. “I believe in property and I believe in making money.” A graduate of Brown University and Harvard Law School, Chafee practiced law in Providence for several years before he joined the Harvard Law School faculty.

Zechariah Chafee was an unlikely champion for First Amendment rights. (Public domain.)

Although a member of the establishment, Chafee had an instinctive sympathy for the underdog. At Brown, a classmate recalled, “his sense of justice did impel him to spring to the defense of any who he felt were unjustly oppressed.” He was also an independent thinker. A colleague on the Harvard Law School faculty remembered him making a commotion in the library. “Every now and then there was a great noise, and I would turn around and Chafee had discovered a new idea and was shouting his pleasure,” he said. Chafee was also eager to establish a career as a writer. Herbert Croly, the editor of The New Republic, gave him his first assignment. Harold J. Laski, a well-known English political scientist, taught at Harvard and knew Chafee. He told Croly that Chafee was working on a scholarly article about freedom of speech during wartime. Croly invited Chafee to submit a summary of his longer work that would be suitable for a general audience. Chafee’s article, “Freedom of Speech,” appeared in The New Republic on November 16, 1918, five days after the war had ended. It was the opening shot in a campaign to create a legal and political defense of free speech that would make it possible to protect dissent in peacetime and enable it to withstand the rigors of the next war.

Zechariah Chafee prompts lawyers to speak against Espionage Act

Chafee said that the country had made a mistake. “Under the pressure of a great crisis,” it had allowed the desire to win the war to become an attack upon freedom of speech. “Judges ... have interpreted the 1917 Act so broadly as to make practically all opposition to the war criminal,” he said. As a result, they threatened a freedom at the core of democracy. “One of the most important purposes of society and government is the discovery and spread of truth on subjects of general concern,” Chafee wrote. “This is possible only through absolutely unlimited discussion.” Chafee acknowledged that government had other purposes that potentially clashed with free speech—maintaining order, educating the young, and providing for national defense. Yet he insisted that protecting freedom of speech was as important as any of the other functions of government. “Unlimited discussion sometimes interferes with these pur- poses, which must then be balanced against freedom of speech, but freedom of speech ought to weigh heavily in the balance,” he argued. “The First Amendment gives binding force to this principle of political wisdom.” During the war, judges had not attempted to strike a balance; they had suppressed any speech that could undermine the war effort. But speech must be free even in wartime, Chafee insisted. “The pacifists and Socialists are wrong now, but they may be right the next time,” he said. “The only way to find out whether a war is unjust is to let people say so.”

The Supreme Court’s decisions upholding the Espionage Act in March 1919 prompted more lawyers to speak out. The Court’s refusal to free Eugene Debs was particularly shocking because unlike the defendants in the other cases, Debs had carefully avoided saying anything that could be construed as an effort to disrupt the draft. Ernst Freund, a distinguished legal scholar at the University of Chicago, was incensed by the Debs decision. “To know what you may do and what you may not do, and how far you may go in criticism, is the first condition of political liberty,” Freund wrote in The New Republic. The “bad tendency” test failed because it allowed judges and juries to decide for themselves what speech was illegal. The Supreme Court had now accepted that standard, Freund said, pointing his finger directly at Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had written the opinions. “Justice Holmes would make us believe that the relation of the speech to obstruction is like that of the shout of Fire! in a crowded theater to the resulting panic,” Freund said. But the parallel was “manifestly inappropriate.” “The peril resulting to the national cause from toleration of adverse opinion is largely imaginary,” he concluded. “In any case it is slight as compared with the permanent danger of intolerance to free institutions.”