Throughout U.S. history, the mail has played a crucial role in shaping jurisprudence on free expression, but its impact on the First Amendment has diminished in recent years, along with its importance as a medium of communication.

Connection of post office and press shaped First Amendment

Beginning in the colonial period, the post office and the press were interconnected in ways that shaped the First Amendment. In the early 18th century, postmasters printed the first colonial newspapers. By the outbreak of the American Revolution, they were publishing most of the colonies’ newspapers. Benjamin Franklin, for example, was both a postmaster and a newspaper publisher.

When the Continental Congress established an independent U.S. post office in 1775, it took over the postal network established by newspaperman William Goddard. It was in part this intimate relationship between mail delivery and the press that prompted Congress to allow newspapers to benefit from extremely cheap (and highly subsidized) mailing rates in the country’s first comprehensive postal statute, which was passed in 1792, just months after ratification of the First Amendment.

Many of the early First Amendment disputes involved the mail

Until World War I and the emergence of a variety of First Amendment issues, many of the most important First Amendment disputes involved the mail. Because the powers of the federal government were far narrower than they are today, Congress’s power over the mail was often its principal means of regulating speech, press, and religion.

An early example of the way in which legislative attempts to control the mail led to a First Amendment clash was the abolitionist mail controversy of 1835–1836. At the time, northern abolitionists were using the mail to send anti-slavery pamphlets to the South. Congress debated several proposals to bar the pamphlets from the mail, but most members considered the proposals unconstitutional, in part because they were thought to abridge freedom of the press. None of the proposals ever became law.

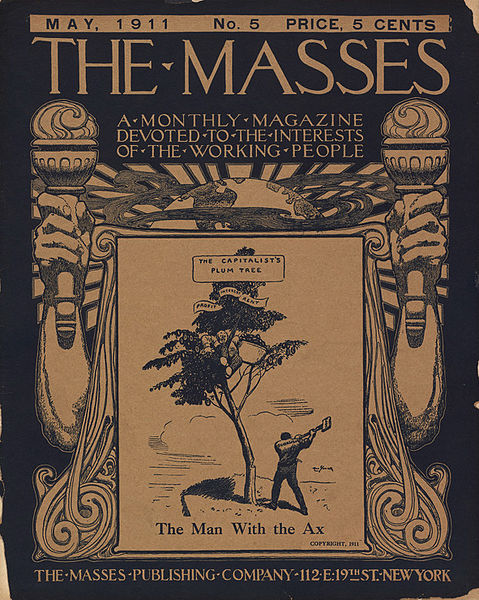

The mail was crucial to federal regulation of the press during World War I. The Espionage Act of 1917 included a provision that prohibited mailing materials that interfered with the war effort (for example, a publication that tended to “obstruct” the draft). In Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917), Judge Learned Hand, a federal trial court judge who later served on the U.S. Supreme Court, attempted to limit the law’s reach to materials that expressly “incited” violation of the law. Although Hand’s opinion, which enjoined the postmaster from barring a newspaper from the mail, was simply a narrow interpretation of the statute and although the decision was reversed on appeal, Masses Publishing is now viewed by many scholars as a turning point in free speech jurisprudence. (Front cover of The Masses May 1911, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Establishment clause conflicted with the mail

The establishment clause and the mail came in conflict in the early nineteenth century. In 1810 Congress passed a law requiring that post offices open at least one hour a day, including Sunday. On and off from 1810 to 1831, religious leaders and others petitioned Congress to change the law. But among the arguments in defense of the law was the claim that a federal law that explicitly recognized the Sabbath would violate the principle of separation of church and state. During the 1850s, Sunday postal service died a slow death, and it effectively ceased altogether after the Civil War (although the 1810 law was not repealed until 1912).

Mail was a First Amendment battleground post-Civil War

The mail continued to be a crucial First Amendment battleground in the post–Civil War years, when Congress passed laws (such as the Comstock Act) banning obscene publications and lottery advertisements from the mail. These laws prompted the Supreme Court to review various cases, but the Court was largely deferential to Congress in its interpretations of the First Amendment during this period. The seminal decision was Ex parte Jackson (1877), which both upheld the constitutionality of the law banning lottery advertisements from the mail and ruled that the obscenity law was constitutional.

The only successful free speech claims during this era were those in which the Court interpreted statutes narrowly. Examples of such interpretations are In re Chase (1890), in which the Court reversed an obscenity conviction on the grounds that the word writings in the obscenity statute did not apply to sealed letters, and Swearingen v. United States (1896), in which the Court ruled that an article that used epithets in attacking an individual was not “obscene.” More typical were cases such as Rosen v. United States (1896), in which the Court affirmed an obscenity conviction based on the mailing of a newspaper with sexually explicit pictures.

The mail provisions of the Espionage Act also produced another important case, United States ex rel. Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v. Burleson (1921). In that case, the Supreme Court upheld an order by the postmaster general denying the newspaper rate (which was cheaper than ordinary mail) to a socialist newspaper on the ground that the paper had violated the Espionage Act. Justices Louis D. Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dissented, and Justice Holmes’s dissent contains the memorable aphorism that “[t]he United States may give up the [post office] when it sees fit, but while it carries it on the use of the mails is almost as much a part of free speech as the right to use our tongues.” Twenty-five years later, the Court overruled the Burleson case. (Postmaster Albert S. Burleson, Dec. 3, 1914, Library of Congress, public domain)

Mail was crucial to federal regulation of press in World War I

The mail was crucial to federal regulation of the press during World War I. The Espionage Act of 1917 included a provision that prohibited mailing materials that interfered with the war effort (for example, a publication that tended to “obstruct” the draft). In Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917), Judge Learned Hand, a federal trial court judge who later served on the U.S. Supreme Court, attempted to limit the law’s reach to materials that expressly “incited” violation of the law. Although Hand’s opinion, which enjoined the postmaster from barring a newspaper from the mail, was simply a narrow interpretation of the statute and although the decision was reversed on appeal, Masses Publishing is now viewed by many scholars as a turning point in free speech jurisprudence.

The mail provisions of the Espionage Act also produced another important case, United States ex rel. Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v. Burleson (1921). In that case, the Supreme Court upheld an order by the postmaster general denying the newspaper rate (which was cheaper than ordinary mail) to a socialist newspaper on the ground that the paper had violated the Espionage Act. Justices Louis D. Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dissented, and Justice Holmes’s dissent contains the memorable aphorism that “[t]he United States may give up the [post office] when it sees fit, but while it carries it on the use of the mails is almost as much a part of free speech as the right to use our tongues.” Twenty-five years later, the Court overruled the Burleson case.

Mail was a First Amendment controversy during Cold War

During the Cold War, the mail again became the subject of a serious First Amendment controversy when Congress passed a law requiring recipients of foreign “communist political propaganda” to return a reply card to the post office indicating a desire to receive the materials. In Lamont v. Postmaster General (1965), the Court invalidated the statute under the First Amendment—the first time the Court struck down a federal statute on free speech/free press grounds.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, many of the seminal obscenity cases involved prosecutions of those who mailed allegedly obscene materials—after all, the mail was still the principal means by which the federal government regulated speech and the press. Among those important cases were Roth v. United States (1957), the first case in which the Court explicitly held that obscenity was not protected by the First Amendment; Manual Enterprises v. Day (1962); and Ginzburg v. United States (1966).

Although some more recent First Amendment cases involve the mail, the focus of such cases has largely shifted to other media.

This article was originally published in 2009. Anuj C. Desai is the William Voss-Bascom Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin, where he teaches in both the Law School and the iSchool. Among his classes are those in First Amendment, Intellectual Freedom, and Cyberlaw. He has published numerous articles on topics related to the First Amendment, including in the Stanford Law Review and Federal Communications Law Journal. Prior to entering academia, Professor Desai practiced law with the Seattle, Washington firm of Davis Wright Tremaine, where his practice included a variety of First Amendment-related matters.