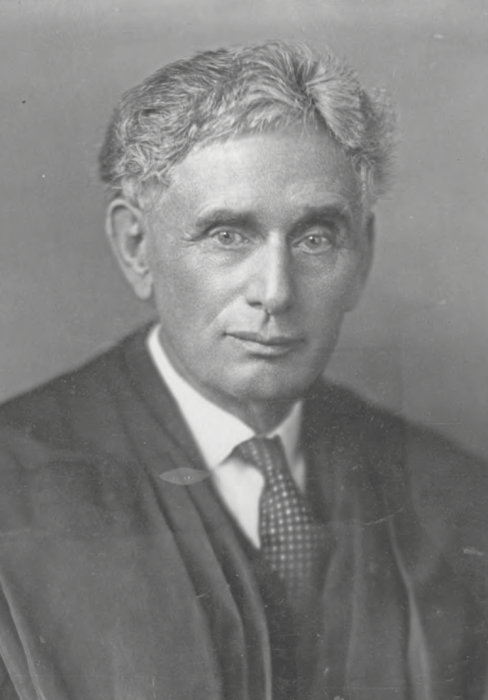

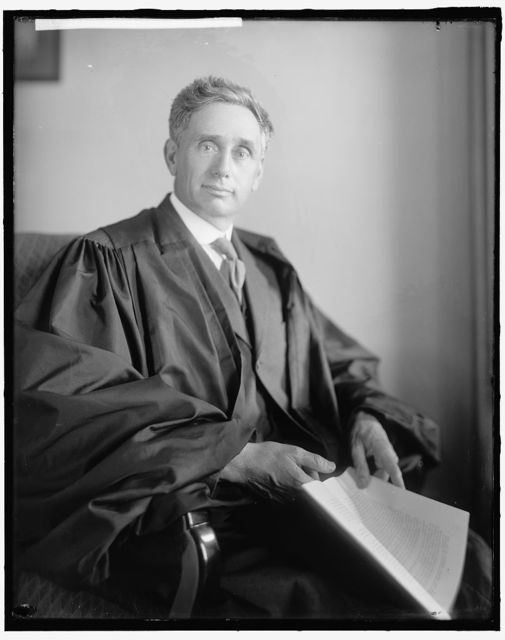

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1856–1941) was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Jewish parents who had immigrated from Bohemia after 1848. At age 18, Louis Brandeis enrolled in Harvard Law School, graduating first in his class in 1877. Working as a lawyer in Boston, he became known as the “people’s attorney” for his involvement in social justice movements and representation of workers’ interests. His advocacy in Muller v. Oregon (1908) included the “Brandeis Brief,” in which he employed extensive empirical data to make the case for restricting the hours of labor for women. Appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to the Supreme Court in 1916, Brandeis became the first Jewish member of the Court and served as an associate justice until 1939.

Brandeis’s stance on free speech evolved

During Brandeis’s tenure, the Court heard a number of important First Amendment cases and began the process of applying the provisions of this amendment to the states as well as to the national government. Brandeis’s stance evolved on issues of free speech from one that upheld governmental restrictions on expression to his concurring opinion in Whitney v. California (1927), which laid out an elegant argument on the virtues of freedom of speech.

Brandeis upheld Espionage Act

Shortly after the United States entered World War I in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, which criminalized the willful obstruction of the military draft, actions causing “insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny or refusal of duty,” and false statements about the armed forces. The law was amended via the Sedition Act of 1918 to include very broad language that, in effect, outlawed statements criticizing the U.S. government.

Although this sedition act was repealed in 1921, the Supreme Court heard a number of cases that fell under its provisions. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote opinions for the Court in three 1919 cases — Schenck v. United States, Frohwerk v. United States, and Debs v. United States — in which the justices, including Brandeis, unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act. According to Holmes, Congress had the authority to limit political speech to protect against a “clear and present danger.” The Court found that during wartime words — in Schenck’s case a pamphlet urging resistance to the draft — were dangerous and therefore not protected speech. Even if the words did not lead to acts that harmed the United States, the speakers or writers could be penalized for the dangers that their words posed.

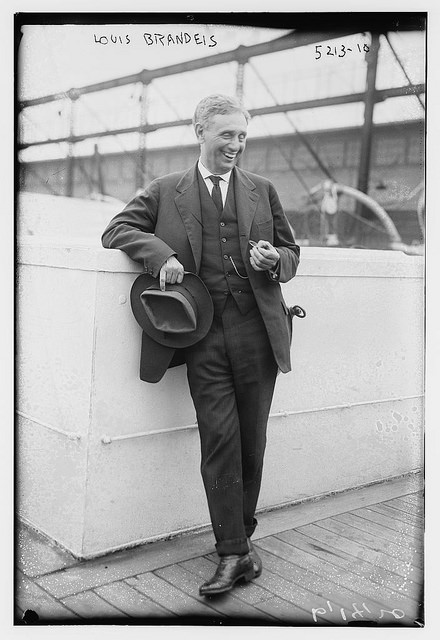

Louis Brandeis circa 1915-1920. During the 1920s Brandeis defended the First Amendment against what he saw as attempts to stifle free expression, and he shared his ideas on the crucial nature of free expression in a democracy. He believed that repression would not defeat radicalism; rather, unorthodox groups should be encouraged to enter into the market competition of the political arena. (Photo by Bain News Service, public domain via the Library of Congress)

Brandeis reinterpreted the “clear and present danger” standard

Later that year, in Abrams v. United States (1919), however, Holmes and Brandeis joined in a dissent that reinterpreted the “clear and present danger” standard that Holmes had articulated in Schenck. Jacob Abrams and his colleagues had written and distributed leaflets criticizing President Wilson for sending American troops to fight in Russia.

Although the Court majority applied the clear and present danger test and found that the leaflets were “an attempt to defeat the war plans of the Government,” Holmes and Brandeis reinterpreted the standard in a more liberal way. The dissenters argued that the First Amendment protected political opinions “unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.” Holmes suggested “that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

Brandeis defended the First Amendment in the 1920s

During the 1920s Brandeis defended the First Amendment against what he saw as attempts to stifle free expression, and he shared his ideas on the crucial nature of free expression in a democracy. He believed that repression would not defeat radicalism; rather, unorthodox groups should be encouraged to enter into the market competition of the political arena. In his dissent in Schaefer v. United States (1920), he stressed that the appropriate response to fiery rhetoric is not censure but calmness. In Pierce v. United States (1920), Brandeis again dissented, arguing that a wide definition of free speech is necessary in a pluralistic political system.

In the years after World War I, a wave of anti-Bolshevik hysteria swept the United States, based on a fear, intensified by occasional bombings and other acts of violence, that the Russian Revolution and its radical ideology would spread around the world. Across the country, states outlawed activities perceived as radical; a majority banned the display of red flags, while some state and local officials were granted the power to silence controversial groups and opinions. It was in such a case, Whitney v. California, that Brandeis wrote his most influential and expansive statement on the subject of freedom of speech. Some scholars have suggested that this concurring opinion provided the theoretical framework for future Courts’ First Amendment jurisprudence.

Brandeis voted with the majority to uphold Charlotte Anita Whitney’s conviction, on non–First Amendment grounds, for violating California’s Criminal Syndicalism Act by belonging to the Communist Party. In his concurring opinion, joined by Holmes, Brandeis addressed free speech issues at length.

He traced the roots of free expression to the intent of the nation’s founders: “They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of American government.”

Louis Brandeis in 1905. According to Brandeis, the founders not only valued free speech as a means to sort out political truths, but they also knew “that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.” (Photo by Harris and Ewing, public domain via the Library of Congress)

Brandeis expressed the counterspeech doctrine

According to Brandeis, the founders not only valued free speech as a means to sort out political truths, but they also knew “that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

He reiterated that an imminent danger of serious evil is the only justification for suppressing free speech. This was in direct contradiction to the view in Schenck that words could be criminalized on the basis of their possible effect at some distant time. Brandeis also expressed what later became known as the counterspeech doctrine, writing that the best remedy to combat harmful speech is “more speech, not enforced silence.”

In 1931 the majority of the Court accepted Brandeis’s position on free speech in Stromberg v. California (1931). Yetta Stromberg, who worked at a summer camp sponsored by the Young Communist League, had been arrested for leading young campers in a daily ritual where they saluted a red flag.

Seven justices signed on to an opinion by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes that echoed the ideas in Brandeis’s Whitney concurrence. They ruled that free political discussion was “essential to the security of the Republic” and a “fundamental principle in our constitutional system.” Brandeis stayed on the Court long enough to see it also adopt the deferential posture toward governmental economic regulation that he had long advocated. He died in 1941, two years after retiring. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed William O. Douglas to replace him.

This article was originally published in 2009. Mary Welek Atwell is Professor Emerita of Criminal Justice at Radford University. She is the author of five books and numerous articles about legal and justice issues. She holds a PhD from Saint Louis University.