The Supreme Court developed several First Amendment doctrines in cases growing out of conflict between various members of the Communist Party and federal and state officials.

In 1919 the left wing of the Socialist Party in the United States split into the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party of the United States. These two groups later merged into the Communist Party of the United States (CPUS) in 1921.

American laws aimed against communists begin during World War I

Congress adopted several statutes aimed at or applicable to communists, including the Alien Registration Act, or Smith Act, of 1940; the Internal Security Act, or McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act; and the Communist Control Act of 1954.

States also adopted criminal anarchy or criminal syndicalism laws aimed at communists, particularly during and after World War I — when communists gained control of Russia in 1917, and after which they often maintained ties to the American Communist Party — and in the 1940s and 1950s during the Red Scare. Such statutes included loyalty oaths and registration requirements, which led to several First Amendment challenges before the Supreme Court.

Federal statutes relating to so-called subversive activities and aimed at the Communist Party resulted in challenges that reached the Supreme Court. In this photo, four women members of the Communist party sit calmly in a police van as they leave Federal Court in New York City, June 20, 1951, en route to the Women’s House of Detention after arraignment on charges of criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the government by force and violence. From left: Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Marion Bachrach, Claudia Jones and Betty Gannett. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918 and corresponding state laws resulted in a number of free speech cases stemming from communist and socialist opposition to World War I. These include:

- Schenck v. United States (1919), in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. formulated the clear and present danger test;

- Abrams v. United States (1919), involving the prosecution of Russian anarchists and Holmes in dissent applying a reinvigorated version of the “clear and present danger” test;

- Gitlow v. New York (1925), in which the Court first applied the free speech guarantee of the First Amendment to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment; and

- Whitney v. California (1927), in which the Court upheld a conviction under a California criminal syndicalism statute, primarily for attendance at the 1919 Communist Labor Party Convention.

Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and other U.S. senators led vigorous congressional investigations into communist activities during the cold war that often subjected communists, or alleged communists, to public ridicule and inclusion on blacklists.

Smith Act challenged

Federal statutes relating to so-called subversive activities resulted in challenges that reached the Supreme Court.

In Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court upheld the section of the Smith Act of 1940 that made it unlawful to advocate or teach the overthrow of government by force or violence or to organize or help to organize a group of persons teaching or advocating such overthrow. The Court stated, “Overthrow of the Government by force and violence is certainly a substantial enough interest for the Government to limit speech.”

In Yates v. United States (1957), the Court interpreted the language of the Smith Act as making it criminal to incite to action for the forcible overthrow of government, but not to teach the abstract doctrine of such forcible overthrow. In doing so, it stated that the “essential distinction is that those to whom the advocacy is addressed must be urged to do something, now or in the future, rather than merely to believe in something.”

Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and other U.S. senators led vigorous congressional investigations into communist activities during the cold war that often subjected communists, or alleged communists, to public ridicule and inclusion on blacklists. In this photo, John Howard Lawson, screenwriter; presses his face close to the microphone as he lashes out at the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington, Oct. 27, 1947, during a tumultuous exchange which ended in his citation for contempt of Congress. He refused to answer questions as to whether he was or had ever been a member of the Communist party. (AP Photo/Beano Rollins, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Scales v. United States (1961), involved a challenge to the membership clause of the Smith Act, which made it a felony to acquire or hold knowing membership in any organization advocating the overthrow of the government by force or violence. The Court upheld the membership clause but interpreted it as requiring that active membership and specific intent were required and also noted that a “blanket prohibition of association with a group having both legal and illegal aims” would pose “a real danger that legitimate political expression or association would be impaired.”

McCarran Internal Security Control Act challenged

Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Control Act of 1950 over the veto of President Harry S. Truman.

In Communist Party of the United States v. Subversive Activities Control Board (1961), the Supreme Court upheld an order that required the Communist Party of the United States to register as a “Communist-action organization” under the act. But later in Albertson v. Subversive Activities Control Board (1965), declared that registration of an individual amounted to self-incrimination and violated the Fifth Amendment.

In United States v. Robel (1967), the Court held as unconstitutional the provision of the law prohibiting employment in any defense facility by a member of a communist organization. The justices found that it abridged the First Amendment’s right of association, noting that the law “sweeps indiscriminately across all types of association with Communist-action groups, without regard to the quality and degree of membership.”

It is important to note, however, that the justices also stated that we “have ruled only that the Constitution requires that the conflict between congressional power and individual rights be accommodated by legislation drawn more narrowly to avoid the conflict,” thus leaving open the possibility for a more narrow restriction of First Amendment rights.

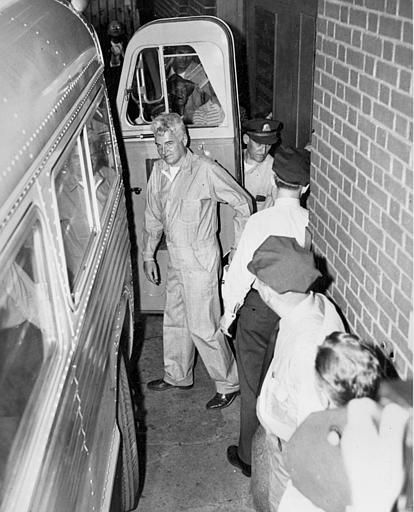

Many portions of the statutes discussed in this article have been repealed in whole or in part. The development of First Amendment rights in the United States owes much to the ideological battle against Communism. In this photo, Eugene Dennis, General Secretary of the Communist Party, is in prison uniform as he boards the bus at Federal House of Detention in New York City, July 6, 1951. He and six other top communists were taken to the Federal Penitentiary at Lewisburg, Pa., to begin sentences for advocating forcible overthrow of the U.S. government. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Challenges to state laws on First Amendment grounds

Communists have also challenged state statutes limiting First Amendment rights.

In De Jonge v. Oregon (1937), the Court struck down a statute because it punished participation in a meeting for lawful discussion of public issues solely because the meeting was “held under the auspices of the Communist Party, an organization advocating criminal syndicalism.” The Court observed that the “greater the importance of safeguarding the community from incitements to the overthrow of our institutions by force and violence, the more imperative is the need to preserve inviolate the constitutional rights of free speech, free press and free assembly in order to maintain the opportunity for free political discussion”

In Elfbrandt v. Russell (1966), the Court struck down a state statute requiring state employees to take an oath not to join the Communist Party with knowledge of its purpose on threat of discharge and perjury.

According to the Court, “Those who join an organization but do not share its unlawful purposes and who do not participate in its unlawful activities surely pose no threat, either as citizens or as public employees.” The justices concluded, “A law which applies to membership without the ‘specific intent’ to further the illegal aims of the organization infringes unnecessarily on protected freedoms. It rests on the doctrine of ‘guilt by association’ which has no place here.”

In Keyishian v. Board of Regents (1967), the Court noted that academic freedom is a special concern of the First Amendment and ruled unconstitutional a state plan requiring faculty members to sign a certificate denying being a communist, or if a communist, having informed the head of the state university of the membership or be subject to dismissal. With this ruling, the Court questioned its previous ruling in Adler v. Board of Education (1952), which had upheld a law making membership in an organization advocating forceful overthrow of government grounds for disqualification from state civil service. Commenting on Adler, the Court observed that “constitutional doctrine which has emerged since that decision has rejected its major premise” which “was that public employment, including academic employment, may be conditioned upon the surrender of constitutional rights which could not be abridged by direct government action.”

Many portions of the statutes discussed here have been repealed in whole or in part. The development of First Amendment rights in the United States owes much to the ideological battle against Communism.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Marcie Cowley was a professor at Michigan State University.