War is often hard on civil liberties, and World War II was no exception. Many events during this conflict challenged the First Amendment rights of individuals.

Civil liberties had different status in WWII than WWI

As the United States was drawn into World War II, many prominent Americans warned against repeating the excesses against dissenters that had characterized the World War I era. There were some abuses, but government officials (particularly in the Justice Department), keenly aware of the tension between civil liberties and unreflective pursuit of public opinion, kept them to a minimum. President Franklin D. Roosevelt at times wanted to squelch the more vocal and extreme critics of his wartime policies, but his subordinates typically resisted his calls for indictments or other repressive measures against dissenters.

Several key differences between the way America entered war in 1917 and 1941 are crucial to understanding the different status of civil liberties in the two eras.

Roosevelt faced less political dissent, more support for WWII than Wilson for WWI

Because the nation was not attacked directly in World War I, in 1917 President Woodrow Wilson, having determined that war was necessary, went to great pains to excite American patriotism and bellicosity. In many ways, he was too successful — and some of his subordinates were even more excessive.

In 1941, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, an America that had resisted Roosevelt’s efforts to assist the Allies suddenly found itself thrust into war. The nature of that attack aroused Americans’ fighting spirit. Fears of disloyalty were not, with one exception, as intense. German Americans and Italian Americans did not encounter the hostility and suspicion that characterized World War I. Instead, Americans’ worst fears and prejudices were displaced onto Japanese Americans throughout the war. In Korematsu v. United States (1944), for example, the Supreme Court upheld the president’s 1942 executive order to exclude them from large areas of California that had been declared war zones and thus effectively approved of their removal to relocation camps.

Roosevelt promised to protect First Amendment liberties

Wilson, in his message asking for a declaration of war in 1917, threatened dissidents, and his attorney general proved himself willing to go far in suppressing civil liberties.

In contrast, as initially neutral Americans became nonbelligerent supporters of the Allies then fellow combatants after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt publicly promised to protect free speech and press.

Between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced into concentration camps in the interior of the United States during World War. This internment is considered the most atrocious attack on civil liberties during this period. In this photo, Japanese citizens gather at a train which will take them from the Santa Anita assembly camp in California to the internment camp at Gila River, Arizona, in 1942. (AP Photo/National Archives, used with permission from the Associated Press)

His attorney general, Francis Biddle, was even more committed to civil liberties, as were Roosevelt’s earlier attorney generals: then Supreme Court justices Robert H. Jackson and Francis (Frank) W. Murphy. The latter had during his tenure at the Justice Department established a Civil Liberties Unit.

With the exception of the fate of Japanese Americans on the West Coast, America did not see in World War II the anti-alien hysteria of 1917–1918. Although the Roosevelt administration investigated and occasionally suppressed pro-Nazi speech, the persons indicted numbered in the dozens as compared with the thousands prosecuted for Espionage Act violations during 1917–1919. Much of the pressure for these indictments came from Roosevelt, who incessantly urged Biddle to “indict the seditionists.” (Roosevelt’s support for civil liberties, powerful in theory, often gave way when his policies were questioned publicly.)

Congress created House Un-American Activities Committee in 1938

Still, with the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, there were Americans who were concerned, not entirely irrationally, about subversives and fifth columnists in their midst. Pearl Harbor did nothing to alleviate their fears. With the political tensions in Europe rising, Congress responded on May 26, 1938, by creating the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which was charged with investigating “the extent, character and objects of un-American propaganda activities in the United States.”

In 1940, with even civil libertarians alarmed by the deteriorating situation in Europe, Congress passed the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (the Smith Act). The most famous provision was its sanctions on persons who “knowingly or willfully” advocated, abetted, advised or taught “the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence.” In effect, this provision was a new sedition act, but it would not reach its full repressive potential until the Cold War era. The same can be said about HUAC.

Supreme Court increasingly upheld rights of dissenters after 1927

Perhaps no branch of the national government changed more dramatically or became more concerned about civil liberties in the period 1920–1940 than the Supreme Court.

From Schenck v. United States (1919) to Whitney v. California (1927), the Supreme Court decided nine First Amendment cases, rejecting the constitutional claims in each. But from 1927 to 1941, the Court upheld First Amendment claims, invoking the “clear and present danger” test in the way Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis had intended.

For example, in Bridges v. California (1941), the Court, summarizing many of these post-Whitney decisions, stated unequivocally that speech could not be punished unless it constituted “a clear and present danger to a substantial interest of the State.”

Court upheld rights of naturalized citizens against efforts to strip citizenship

During the war, the Supreme Court moved, albeit cautiously, to protect free speech. Key decisions were drawn narrowly, but the rights of dissenters were upheld. For example, in Schneiderman v. United States (1943) the Court encountered an effort by the government to cancel Schneiderman’s naturalization.

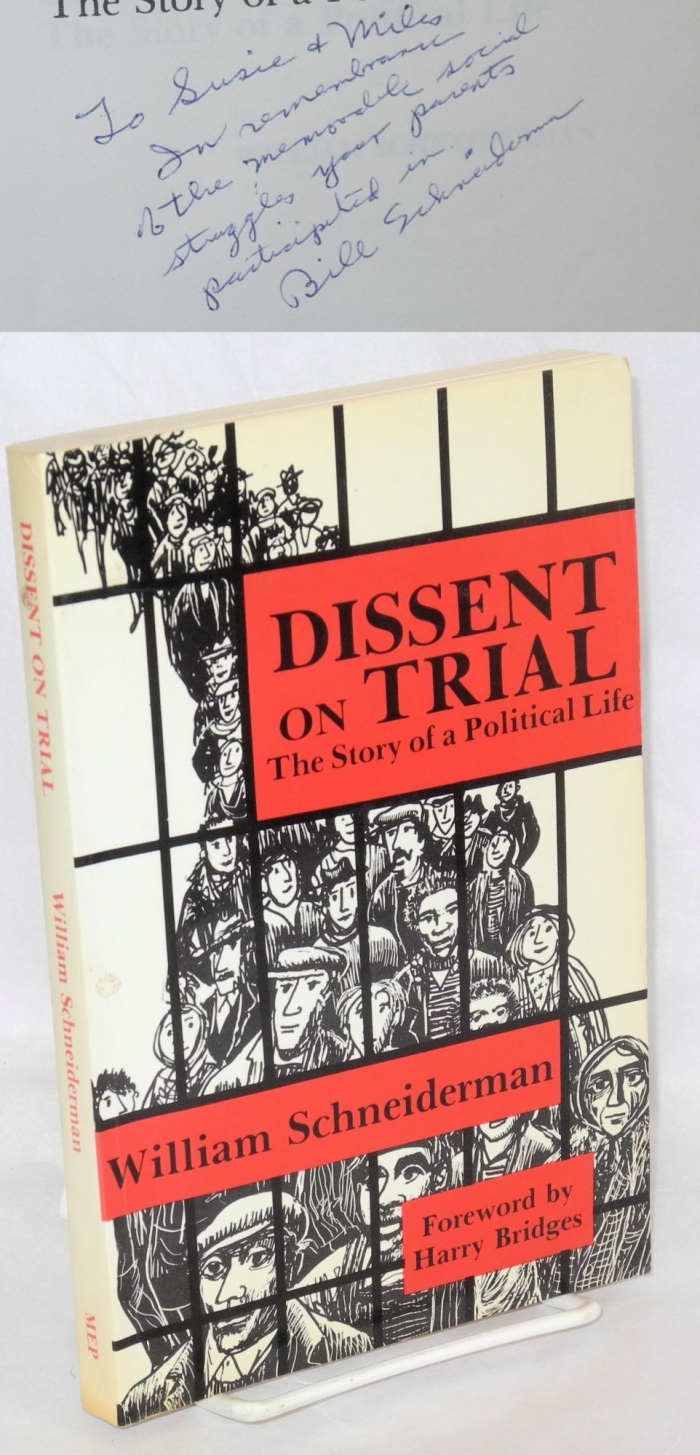

In a World War II-era case, the government tried to strip citizenship of naturalized citizen William Schneiderman, who led the Communist Party in California. But the Supreme Court held in 1943 that his party membership did not necessarily indicate opposition to the American constitution. In 1952, Schneiderman was convicted of conspiring to advocate the overthrow of the government by force. This conviction was also reversed by the Court. Schneiderman wrote a book about his legal battles, Dissent on Trial (book cover image above).

The government alleged that his involvement with the Communist Party meant that he could not be considered “attached to the principles of the Constitution,” and that his citizenship was thus obtained by fraud (grounds in federal law for canceling naturalized citizenship). Justice Murphy rejected the government’s argument, holding that Schneiderman’s party membership did not necessarily indicate opposition to the philosophy of the Constitution. The government would have to prove that the individual had personally advocated “present violent action which creates a clear and present danger.”

In Baumgartner v. United States (1944), the Court expanded on Schneiderman and ruled that Carl Wilhelm Baumgartner could not be denaturalized for his open and vocal support of Adolf Hitler and the doctrine of Aryan supremacy. The Court noted that if native-born citizens are free to make such statements, so are naturalized citizens.

Court reversed convictions for ‘subversive’ advocacy

The Court also addressed the issue of prosecutions for “subversive” advocacy. In Taylor v. Mississippi (1943), the defendant had complained that Americans were being killed in the war for no good purpose. The Court held that even in wartime, such statements, clearly allowable in time of peace, could not be the basis for criminal sanctions. In Hartzel v. United States (1944), the defendant was convicted under the Espionage Act for distributing anti-Semitic and anti-Roosevelt pamphlets. Reversing his conviction, the Court stressed that even “immoderate and vicious invective” was protected by the First Amendment.

The Roosevelt administration, not eager to repeat the experience of World War I, restrained state and local governments’ efforts to address issues of loyalty and security. Both the president and Attorney General Jackson in 1940 publicly warned against “the cruel stupidities of the vigilante” or mob violence against those who were different or held unpopular opinions.

Jehovah’s Witnesses targeted by vigilantes because of opposition to all war

Aside from persons of Japanese descent, Jehovah’s Witnesses were the group most frequently targeted for vigilantism, undoubtedly because of their opposition to all war and their refusal to salute the flag. During World War II, approximately 500 Witnesses, according to Geoffrey R. Stone (2004), “were beaten by mobs, tarred and feathered, tortured, castrated, or killed in more than forty states. In some of these incidents, local officials participated in the mob actions” (p. 279). These actions began to taper off only when the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division threatened local officials with federal prosecution.

In short, America in World War II did not see the kinds of restrictions on civil liberties that ran rampant in World War I, and a generous share of the credit belongs to Justice Jackson and his equally courageous colleagues, Frank Murphy and Francis Biddle.

This article was originally published in 2009. Philip A. Dynia is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department of Loyola University New Orleans. He teaches constitutional law and judicial process as well as specialized courses on the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment.