Throughout his storied legal career, which included 13 years on the Supreme Court, Robert Houghwout Jackson (1892–1954) was a strong advocate of the First Amendment, but his advocacy was not without its limits.

Raised in western New York, Jackson was largely a self-taught lawyer. After reading law with a local attorney, he completed a two-year law course at Albany Law School in one year and was admitted to the New York bar in 1913, when he was 21 years old.

Jackson served Roosevelt administration before becoming Supreme Court justice in 1941

Jackson’s first exposure to politics, as a Democratic committeeman, convinced him that he preferred practicing law to pursuing politics. However, he still managed to catch the eye of New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed him to a commission studying the New York state judicial system.

Later, during Roosevelt’s tenure as president, Jackson served in several capacities in the federal government: special counsel to the Securities and Exchange Commission, U.S. assistant attorney general, U.S. solicitor general, U.S. attorney general, and, from 1941 until his death in 1954, Supreme Court justice.

During a year-long leave of absence from the Court, he served as chief U.S. prosecutor of Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, Germany.

Supreme Court Associate Justice Robert Jackson in 1953 at a dinner of the Alfalfa Club. While on the Supreme Court, Jackson tended to be a strong supporter of civil liberties, including those found in the First Amendment. For example, he believed in a high wall of separation between the church and state. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In First Amendment cases, Jackson believed in wall of separation between church and state

While on the Supreme Court, Jackson tended to be a strong supporter of civil liberties, including those found in the First Amendment.

For example, he believed in a high wall of separation between the church and state. He thus dissented in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), when the majority held that New Jersey had not violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment when it reimbursed parochial school parents the cost of busing their children to public school.

He also dissented from the ruling in Zorach v. Clauson (1952), which allowed public schoolchildren to leave school grounds to attend religious education or observance.

Jackson wrote majority opinion about forcing students to salute the flag, recite Pledge of Allegiance

Jackson wrote the majority opinion in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) in which the Court ruled that a school could not compel a student to salute the U.S. flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

Jackson famously wrote: “The very purpose of the Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts.”

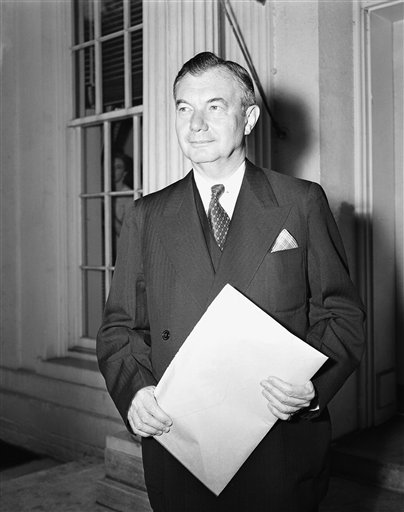

Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson leaving the White House in 1946. Jackson’s defense of the First Amendment was not without its limits; he generally advocated judicial restraint. In his view, the First Amendment freedoms ensured that citizens could make their discontent public so that the subject of that discontent could be addressed publicly. (AP Photo/William J. Smith, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Jackson did not believe in unchecked rights or ‘liberty without law’

Jackson’s defense of the First Amendment was not without its limits, however; he generally advocated judicial restraint.

In his view, the First Amendment freedoms ensured that citizens could make their discontent public so that the subject of that discontent could be addressed publicly. Moreover, although all citizens had the obligation to tolerate and reply to open dissent, no matter how disagreeable, “this concept of liberty had no tolerance of any form of lawlessness, no belief that there could be freedom except under law.”

In addition, the protections afforded by the Constitution “must not be discredited by an interpretation to mean liberty without law. Nothing can do the cause of liberal government more harm . . . than to give . . . the impression that our Bill of Rights is useful only to our enemies or is a mere refuge for criminals.”

In a separate address, Jackson was a bit clearer about his fear of unchecked rights. He argued that classifying the freedoms of speech, press, and assembly as “preferred freedoms” was problematic because communists (and by implication others who advocate the overthrow of the U.S. government) invoke these preferred rights to shelter themselves from legal recourse if they are attacking the government.

The clearest example of Jackson’s fear of unchecked liberty was his “suicide pact” line from Terminiello v. Chicago (1949) in which a speech incited a riot. Jackson claimed that “There is danger that, if the Court does not temper its doctrine logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.” (1945 photo via the Library of Congress, public domain)

Jackson said without wisdom, Bill of Rights could be converted into a ‘suicide pact’

The clearest example of Jackson’s fear of unchecked liberty was his “suicide pact” line from Terminiello v. Chicago (1949) in which a speech incited a riot.

Jackson claimed that “[t]his Court has gone far toward accepting the doctrine that civil liberty means . . . that all local attempts to maintain order are impairments of the liberty of the citizen. The choice is not between order and liberty. It is between liberty with order and anarchy without either. There is danger that, if the Court does not temper its doctrine logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.”

Serving as Nuremberg trials prosecutor influenced Jackson’s view on First Amendment

Scholars have noted that Jackson altered his stance on the protections afforded by the First Amendment after his service as prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials.

For example, although he explicitly defended the preferred position doctrine (granting special priority to First Amendment freedoms) soon after his appointment to the Supreme Court, he later rejected the doctrine. He did, however, continue to emphasize the importance of rights for the accused and protections from warrantless searches.

In the end, it is perhaps best to describe Jackson as a civil libertarian, but one who was fearful of allowing unfettered action based on the belief that the First Amendment freedoms themselves had few or no limits.

This article was originally published in 2009. Tobias T. Gibson is the John Langton Professor of Legal Studies and Political Science at Westminster College in Fulton, MO.