Early in the 20th century, the Supreme Court established the clear and present danger test as the predominant standard for determining when speech is protected by the First Amendment.

The Court crafted the test — and the bad tendency test, with which it is often conflated or contrasted — in cases involving seditious libels, that is, criticisms of the government, its officials, or its policies. It would be superseded by the imminent lawless action test in the late 1960s.

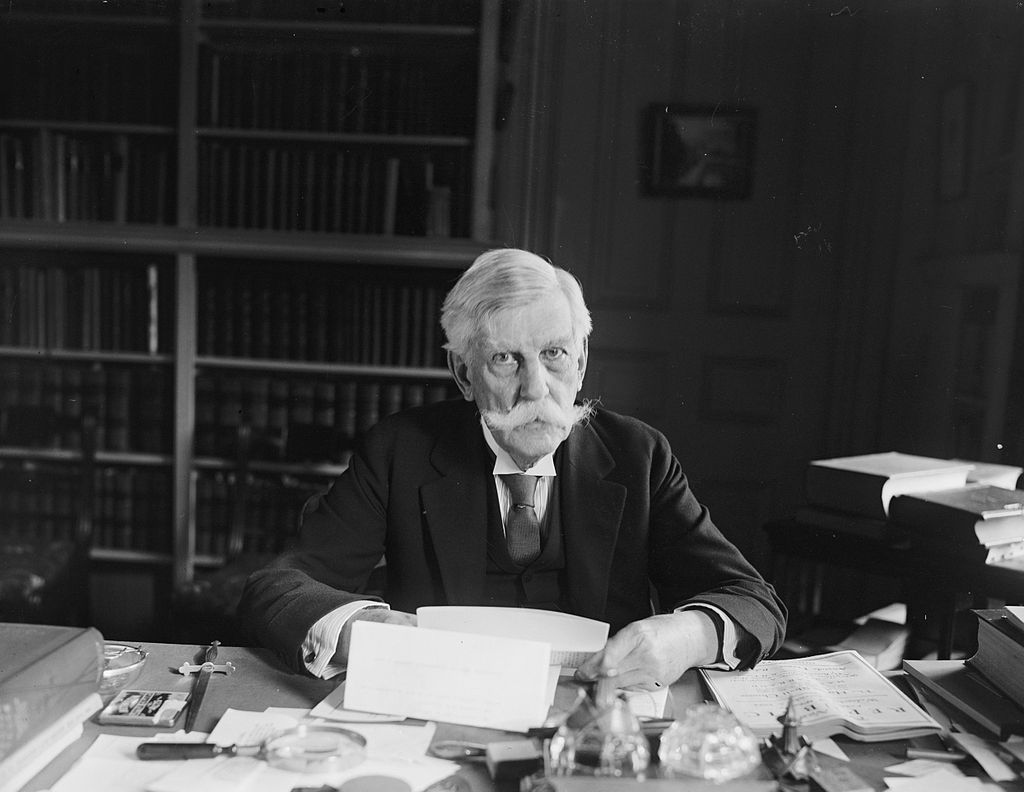

Holmes introduces idea of clear and present danger test

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. delivered the classic statement of the clear and present danger test in Schenck v. United States (1919): “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.”

In Schenck, Justice Holmes clearly distinguished the clear and present danger test from the bad tendency test — which was predominant in English common law and would be articulated in Gitlow v. New York (1925) — when he stated that “in time of peace,” the pamphleteer and co-defendants “would have been within their constitutional rights.”

The clear and present danger test is different from the bad tendency test — which was predominant in English common law and would be articulated in Gitlow v. New York (1925), a case involving the conviction of Benjamin Gitlow for publishing material that advocated the Communist reconstruction of society. The Supreme Court observed in Gitlow, “Freedom of speech and press . . . does not protect publications or teachings which tend to subvert or imperil the government or to impede or hinder it in the performance of its governmental duties.” The bad tendency test protects only innocuous speech; it criminalizes all seditious libels. Gitlow is shown in this 1939 photo. (AP Photo/Charles Gorry, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Distinction from bad tendency test

The bad tendency test provides that when the facts of a case indicate that the communicator intended a result that the state has prohibited, the court may reasonably assume that the communication has a tendency to produce that result.

Furthermore, on the basis of that tendency, the court may punish the communicator for violation of the law. For example, if a pamphleteer urges conscripts to resist military conscription, and if a law criminalizes noncompliance, judges may rightfully conclude that the pamphlet has a tendency to encourage violations of the law and therefore convict the pamphleteer.

In contrast to the clear and present danger test, the bad tendency test proposes no distinction based upon circumstances. The Supreme Court observed in Gitlow, “Freedom of speech and press . . . does not protect publications or teachings which tend to subvert or imperil the government or to impede or hinder it in the performance of its governmental duties” (italics added). The bad tendency test protects only innocuous speech; it criminalizes all seditious libels.

Holmes dissent says imminent danger must be present

Justice Holmes ultimately found the clear and present danger test as articulated in Schenck insufficient to protect basic constitutional rights. Thus, in his dissent later in the year in Abrams v. United States (1919) he wrote that “we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions . . . unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purpose of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.”

Thus, he elevated the danger requirement from “clear” to “imminent” interference with legal action.

Justice Louis D. Brandeis further elaborated upon the test in his concurring opinion (which Holmes joined) in Whitney v. California (1927), when he argued that the “evil apprehended” as a result of expression should be “so substantial as to justify the stringent restriction apprehended by the legislature.”

Adoption of clear and present danger test

The clear and present danger test was not accepted by a majority of the Supreme Court until Herndon v. Lowry (1937), when Justice Owen J. Roberts invoked it while rejecting the bad tendency test as an appropriate standard for identifying the protections of the First Amendment.

From 1940 to 1951, the Court employed the clear and present danger test to decide 12 cases.

In American Communications Association v. Douds (1950), however, the Court had begun to switch gears when it assessed the constitutionality of a statute aimed not at political expression but at political strikes in the communications industry.

For the majority, Chief Justice Frederick M. Vinson wrote, “When the effect of a statute or ordinance upon the exercise of First Amendment freedoms is relatively small and the public interest to be protected is substantial, it is obvious that a rigid test requiring a showing of imminent danger to the security of the Nation is an absurdity.”

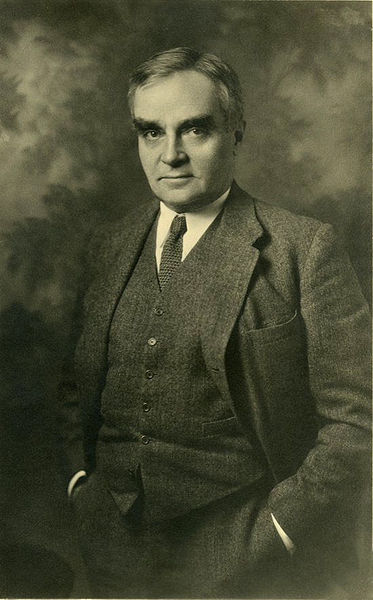

The clear and present danger test was revised into the gravity of the evil test. Judge Learned Hand of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals adapted the revision in United States v. Dennis (1950): “Clear and present danger depends upon whether the mischief of the repression is greater than the gravity of the evil, discounted by its improbability.” Hand is shown in this 1910 photo. (Photo via Harvard Library, public domain)

“Gravity of evil” introduced as a balance test

Vinson then reconstructed the clear and present danger test: “[N]ot the relative certainty that evil conduct will result from speech in the immediate future, but the extent and gravity of the substantive evil must be measured by the test laid down in the Schenck case.”

Judge Learned Hand of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals adapted the Vinson revision in United States v. Dennis (1950): “Clear and present danger depends upon whether the mischief of the repression is greater than the gravity of the evil, discounted by its improbability.” Vinson embraced this rephrasing when Dennis was appealed to the Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States (1951).

Professor Samuel Krislov wrote that the clear and present danger standard had been transformed into a balancing test, “so completely blurred” that it served only to provide “apologetic acceptance of all legislative action” (p. 88).

Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas agreed.

When Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), reached the Court, Black demanded that Justice Abe Fortas remove all references to the test from his draft opinion for a unanimous Court. Fortas refused, but resigned from the Court before the announcement of the decision in Brandenburg.

“Imminent lawless action” test supplants “clear and present danger” test

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. redrafted the per curiam opinion, substituting for clear and present danger a new standard (Schwartz 1995: 27): “The constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

The imminent lawless action test has largely supplanted the clear and present danger test. The clear and present danger remains, however, the standard for assessing constitutional protection for speech in the military courts.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.