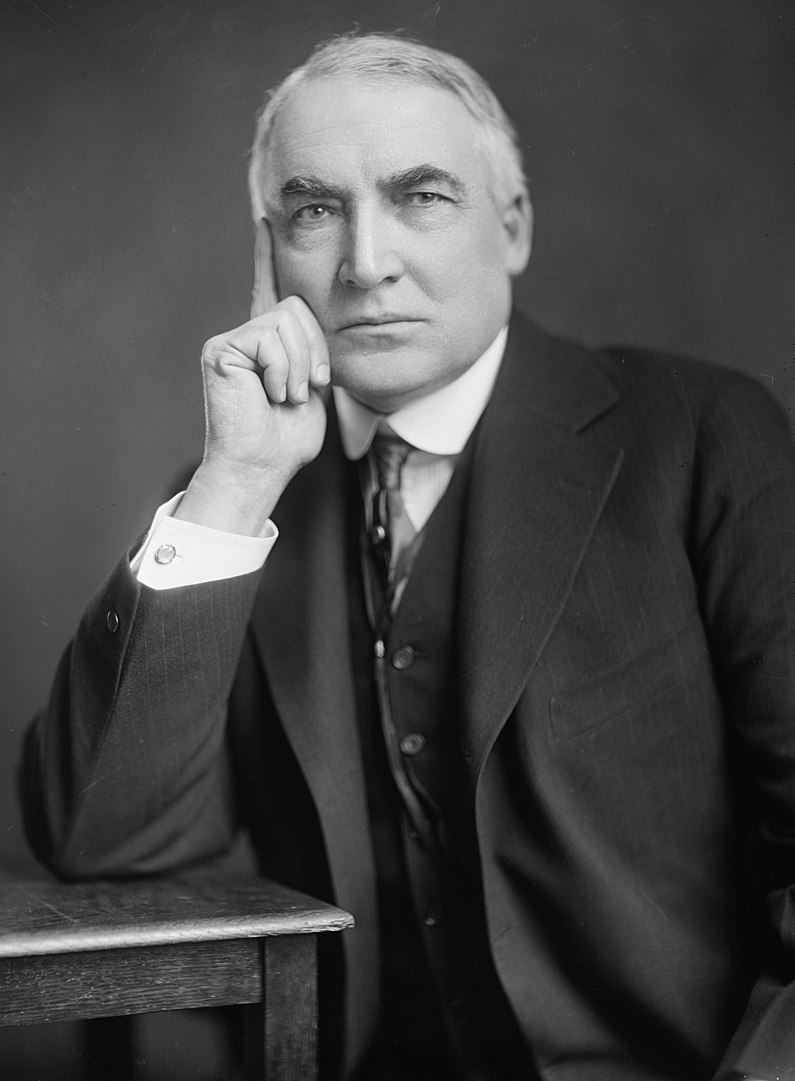

Warren G. Harding served as the nation's 29th president from 1921 until his death in 1923. His presidency followed after Woodrow Wilson's with a promise of restoring “normalcy” after World War I. He is usually regarded as one of the least effective individuals to hold the presidency.

Born in 1865 and raised in Ohio, he earned his bachelor’s degree at Ohio Central College and, after dabbling in a number of jobs, purchased the Marion Star newspaper and turned it into a publishing success.

He served respectively as a member of the Ohio senate, as lieutenant governor of the state, and as one of its two U.S. senators before being elected in 1920 on a ticket with Calvin Coolidge against Democrat lawyer James M. Cox, who, like Harding, was from Ohio. Harding was the first president elected in the aftermath of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which had extended the right to vote to women.

Although Harding made some good cabinet choices, including Herbert Hoover as Commerce secretary, and Andrew Mellon as Treasury secretary, he often relied on cronies who used their positions for personal gain. His attorney general, Harry Daughtery, and his secretary of the Interior, Albert Fall, undermined faith in government. Fall was involved in the Teapot Dome Scandal in which officials were bribed to give favorable noncompetitive government land leases to oil companies.

Harding pardoned Eugene Debs of sedition sentence under Wilson

In a speech on July 22, 1920, advocating “Liberty Under Law,” Harding, in commenting on subversive movements, observed that:

“We must not abridge the freedom of speech, the freedom of press, or the freedom of assembly, because there is not promise in repression. These liberties are as sacred as the freedom of religious beliefs, as inviolable as the rights of life and the pursuit of happiness.”

He added, however:

“We do hold to the right to crush sedition, to stifle a menacing contempt for law, to stamp out a peril to the safety of the Republic or its people when emergency calls, because security and the majesty of the law are the first essential of liberty. He who threatens destruction of the government by force, or flaunts his contempt for lawful authority, ceases to be a loyal citizen and forfeits his right to the freedom of the Republic.”

There was considerable opposition to U.S. participation in World War I, and the Wilson Administration had clamped down on public dissent with the adoption of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, under which socialist Eugene Debs had been jailed. After Debs’ imprisonment was upheld in Debs v. United States (1919), Harding commuted his sentence in 1921, the same year that Congress repealed most of the 1921 law.

Presidential scholar James D. Robenalt observed that “Harding’s strategic use of the presidential pardon helped undo the damage done by a war-frenzied Congress in enacting the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which had been compounded by the failure of the Supreme Court to defend the First Amendment of the Constitution. It was an impressive demonstration of constitutional authority by a president.”

At the time that Harding was in office, the Supreme Court was still operating under the precedent in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), which confined the application of the First Amendment, and other provisions of the Bill of Rights, to the national government. In Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), however, the high court used the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to strike down a state law that had prohibited the teaching of German in schools. During Calvin Coolidge’s presidency that followed, the Supreme Court would decide in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that the provisions of freedom of speech and of the press applied to the states via the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, and, over time, all the other provisions of the First Amendment, and most other provisions within the Bill of Rights, were also applied to the states.

FBI seized books about Harding's unsavory activities; books burned

Harding flouted prohibition laws while in the White House and had a number of mistresses, some of whom tried to blackmail him. His wife Florence had been divorced prior to marrying him and had given up custody of her son to her father who opposed her subsequent marriage to Harding. In 1922, governmental agents had forced William Estabrook Chancellor, a historian and Democrat who had previously taught at the College of Wooster, which fired him, to burn a manuscript with these and other allegations.

Although Chancellor had fled to Canada, in 1922, the Sentinel Press made a subsequent attempt to publish a book in Ohio under the title of The Illustrated Life of President Warren G. Harding, attributed to Chancellor who denied authorship. It included unproven allegations that Harding had one or more African American ancestors.

When attorney general Harry Daughtery learned of this, he sent FBI agents to seize the books, and secure those that had been sold by buying them back. These were subsequently burned in a bonfire at the home of a Harding friend. This is said to have been “The only book published in peacetime to be suppressed by the United States government” (Anthony 1998, xviii).

Chancellor later returned to Ohio and taught at Xavier University in Cincinnati.

Harding appoints William Howard Taft as chief justice

Harding’s most important appointment as president may have been that of former president William Howard Taft, whom Harding nominated as chief justice.

Responsible for streamlining the operations of the Supreme Court, the Taft Court remained better known for striking down legislation such as federal minimum wage laws for women in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) than for protection of First Amendment freedoms.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 29, 2023.