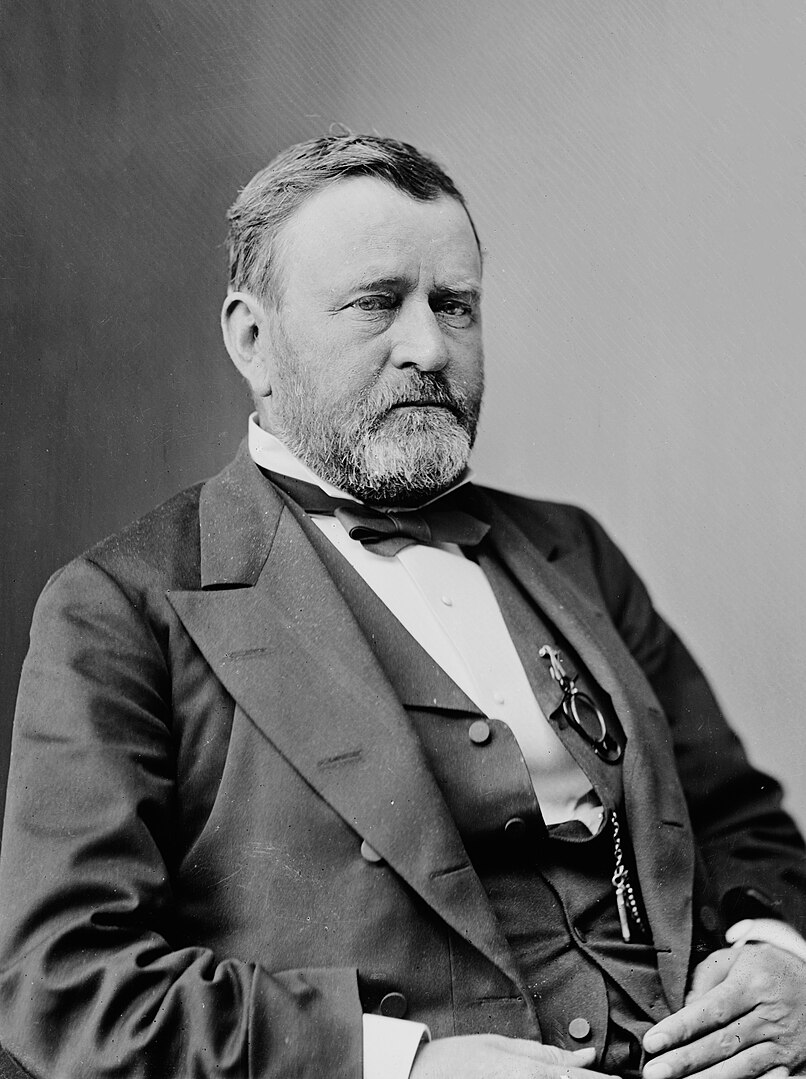

Ulysses (born Hiram) S. Grant (1822-1885) was born in Ohio to the family of a tanner. He attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where, because of a paperwork mistake, his name was changed from Hiram to Ulysses and he became known as U.S. Grant.

After resigning from the Army in 1854 and returning home to farm, Grant rejoined in 1861 during the Civil War. He rose through the ranks with successive victories to become the commanding general to whom Confederate Army commander Robert E. Lee eventually surrendered at the Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia, effectively bringing an end to the conflict.

President Andrew Johnson subsequently appointed Grant as Secretary of War (Johnson’s firing of Edwin Stanton, Grant’s predecessor in this post, was one of the factors that led to Johnson’s impeachment). The Republican Party nominated Grant for president in 1868. He served two full terms, was succeeded by Rutherford B. Hayes, and vied unsuccessfully for renomination in 1880, which went instead to James A. Garfield, whom Grant supported.

Grant favored equal rights for African Americans, Jews

As he entered the presidency, Grant had hoped to replace a time of turmoil with a time of peace. He favored equal rights for African Americans and Jews, and he sought fair treatment for Native American Indians. He advocated for the 15th Amendment, which was designed to prevent denial of voting rights to African American men, and he pressed for civil rights legislation, much of which was watered down by the Supreme Court.

Federal troops remained in the South throughout Grant’s tenure in office, and he called upon them on a number of occasions to protect African American rights. Congress did not adopt his plan to annex Santo Domingo (today’s Dominican Republic) as the site of a U.S. naval base and a place for former U.S. slaves to seek a better life for themselves.

Supreme Court limits application of 14th Amendment post-war

At the time of Grant’s presidency, the Supreme Court was still following the precedent announced in

Although Grant had successfully pushed for the Enforcement Act of 1870, the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, Supreme Court decisions in U.S. v. Cruikshank (1875) the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, and United States v. Harris (1883) limited federal enforcement of the 14th Amendment against official state action rather than private action. The court’s decision in the Slaughterhouse Cases of 1873 further ruled most privileges and immunities mentioned in the 14th Amendment remained under state rather than federal jurisdiction, thus limiting the scope of this guarantee.

Grant strongly favored separation of church and state

One questionable action with which Grant was associated was his issuance of General Orders No. 11 of Dec. 17, 1862, while he was a Civil War commander. The order required eviction of Jews from the vast area under his Army command for their alleged trading with the Southern enemy.

Fortunately, President Abraham Lincoln expeditiously overruled the order declaring that he did not “like to hear a class or nationality condemned on account of a few sinners” (Sarnia).

As president, however, Grant appointed a number of Jews to governmental posts and supported their efforts to keep church and state separate. He was the first president to attend the dedication of a synagogue, and he invited Jews to meet with him in the White House.

In his First Annual Message of Dec. 6, 1869, Grant lauded “freedom of the pulpit, the press, and the school.” Favoring education as a means of promoting democratic-republican government, Grant gave a speech to veterans of the Army of the Tennessee that he had commanded on Sept. 29, 1875, in which he called for supporting “all needful guarantees for the more perfect security of free thought, free speech, and a free press, pure morals, unfettered religious sentiments and of equal rights and privileges to all men, irrespective of nationality, color or religion.”

Grant went on in this speech to “resolve that not one dollar of money appropriated to their support, no matter how raised, shall be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school.” He favored common schools “unmixed with sectarian, pagan or atheistical tenets.” He advised, “Leave the matter of religion to the family circle, the church and the private school, supported entirely by private contributions. Keep the Church and State forever separate.”

Many states began adopting so-called Blaine Amendments during this time period to bar the use of state monies for parochial schools. Moreover, in Board of Education of the City of Cincinnati v. Minor (Ohio S. Ct. 1872), a state high court upheld a decision prohibiting religious instruction from the Bible in public schools.

In addition to opposing aid to church-sponsored schools, Grant feared the growing amount of church lands that were not subject to taxation. In his annual address to Congress in 1875, he proposed “the taxation of all property equally, whether church or corporation, exempting only the last resting place of the dead and possibly, with proper restrictions, church edifices.”

In a related matter, in Watson v. Jones (1871), the Supreme Court ruled that it would resolve disputes over church property according to denominational rules rather than by deciding between rival church doctrines.

Congress adopts Comstock Act during Grant’s presidency

In other action that implicated the First Amendment during the Grant Administration, Congress adopted the Comstock Act of 1873, which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious,” “immoral,” or “indecent” materials through the mail, including birth control devices or information. In Ex parte Jackson (1877), it further allowed congressional bans on the sale or advertising of lottery tickets through the mail.

Reputation and legacy

A number of Grant’s appointees were caught up in scandal, and his hopes to provide equal protection for former slaves proved illusory.

After losing most of his money after he left the presidency, Grant spent his last months, during which he was battling cancer, writing his classic two-volume personal memoirs. He died a much lauded and beloved president, whose tomb is still a tourist attraction in New York.

Grant appointed four justices to the Court. They were:

- William Strong, who served from 1870 to 1880;

- Joseph Bradley who served from 1870 to 1892;

- Ward Hunt, who served from 1872 to 1882; and

- Chief Justice Morrison Waite who served from 1874 to 1888.

They were no more supportive of most of Grant’s efforts to enforce and expand civil rights for all than the colleagues they joined on the bench.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 15, 2023.