In Watson v. Jones, 80 U.S. 679 (1871), the Supreme Court ruled that it would resolve disputes relative to church property on a basis other than an examination of church doctrine, thus making the conflict between church and state less likely and arguably furthering the goals of the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

The Watson decision established important principles that have since “dominated all subsequent jurisprudence on the resolution of internal religious disputes” (Gerstenblith 1990: 522).

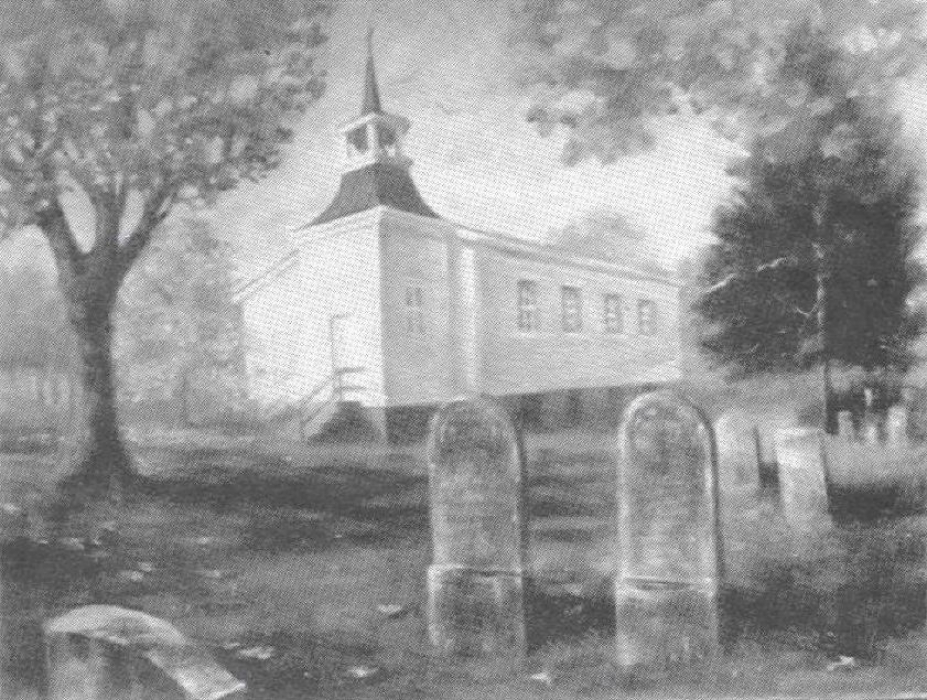

Dispute over slavery divided Kentucky church

The Watson case involved a dispute between the pro- and anti-slavery factions within the Third or Walnut Street Presbyterian Church of Louisville, Kentucky, both of which claimed church property. The two factions disagreed not only about the divisive issue of slavery, but also about fundamental issues of church management, such as whether the church should retain the services of a particular pastor and the selection and retention of church elders.

Justice Samuel F. Miller’s decision for the high court rested on the premise that “[r]eligious organizations come before us in the same attitude as other voluntary associations for benevolent or charitable purposes, and their rights of property or of contract are equally under the protection of the law and the actions of their members subject to its restraints.”

After deciding that the Court had jurisdiction, Miller proceeded to divide disputes like the one before the Court into three categories.

Supreme Court declines to be arbiter of church doctrine

First, in cases about clearly defined private trusts, the court was responsible for seeing that property so dedicated went to its intended purpose, even if such a responsibility meant examining doctrine.

Second, in cases about independent churches, the court must apply the same rules it would apply to other such voluntary organizations, leaving the majority of members or the congregation officers (as church rules specified) to decide on church doctrine.

And, third, in cases about churches affiliated with larger denominations, the court should operate by the principle that “whenever the questions of discipline or of faith or ecclesiastical rule, custom, or law have been decided by the highest of these church judicatories to which the matter has been carried, the legal tribunals must accept such decisions as final.”

Miller recognized that the latter approach differed from that in Britain, where judges routinely made such determinations, but he reasoned that whereas Britain did not grant full religious freedom, “[i]n this country, the full and free right to entertain any religious belief, to practice any religious principle and to teach any religious doctrine which does not violate the laws of morality and property, and which does not infringe personal rights is conceded to all. The law knows no heresy, and is committed to the support of no dogma, the establishment of no sect.”

Court: Denomination’s rules govern ecclesiastical affairs

Because the members of the church voluntarily associated themselves with a denomination, its rules governed ecclesiastical affairs. In the case at hand, both the majority of the congregation and the church hierarchy supported the anti-slavery faction, with whom the Supreme Court therefore sided.

Justice Nathan Clifford authored a dissent, in which Justice David Davis joined, essentially disputing jurisdiction in the case of the court whose decision the majority was reviewing.

Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral (1952) and Presbyterian Church in the United States v. Mary Elizabeth Blue Hull Memorial Presbyterian Church (1969) later affirmed Watson’s principle of preventing courts from determining the true beliefs of a church. Presbyterian Church classified Watson as being “informed by First Amendment considerations.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.