The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873), represents the first instance in which the court interpreted the 14th Amendment.

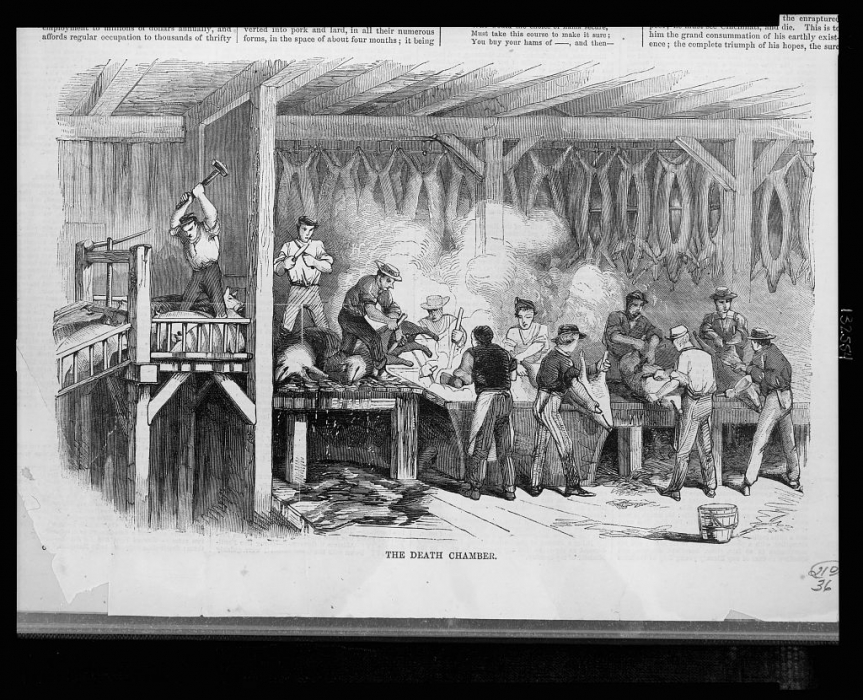

In this case, which was a consolidation of three similar cases, the court rejected a claim that butchers in New Orleans filed against a set of state regulations directing that all butchering take place in selected abattoirs.

The butchers argued that these regulations violated the privileges and immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Court rejected butchers’ claims, narrowly interpreted 14th Amendment

In its ruling, the court offered a narrow interpretation of that clause, with significant implications for the future application of First Amendment rights to the states.

In rejecting the butchers’ argument, Justice Samuel Miller distinguished between the limited number of privileges and immunities of U.S. citizens, which are protected by the14th Amendment, and the wider set of rights possessed by state citizens, which are protected at the state level.

Miller thought the pervading purpose of the 14th Amendment had been that of protecting former slaves, and he hesitated to expand its protection for fear of altering the distribution of powers between the state and national governments. He thought that the state regulations at issue, which appear to have been influenced both by genuine health concerns and by legislative deal making, could be justified as a legitimate exercise of state police powers.

Justice Miller suggested First Amendment rights may be incorporated to states

Significantly, in describing the limited number of rights that he believed the privileges and immunities clause of the 14th Amendment protected, Miller listed “[t]he right to peaceably assemble and petition for redress of grievances,” which he presumably derived from the First Amendment.

He connected privileges and immunities with the right “to come to the seat of government to assert any claim he may have upon that government, to transact any business he may have with it, to seek its protection, to share its office, [and] to engage in administering its functions.”

Four justices, led by Justice Stephen Field and joined by Salmon Chase, dissented. Field focused on using the 14th Amendment not to protect the rights embodied in the First Amendment but to protect economic rights.

14th Amendment later incorporated First Amendment rights to states

The “incorporation” of provisions of the First Amendment into the 14th Amendment did not begin until the Court’s decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925). In this and in later cases the court chose to rely chiefly on the due process clause rather than on the privileges and immunities clause.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.