The Blaine amendments—a series of amendments to state constitutions in the late 19th century—aimed to prevent the use of public funds to support parochial schools. In effect, they sought to augment the more general language of the establishment clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution by explicitly placing restrictions on the use of public funds by states for the support of religious institutions.

Blaine wanted to ensure that taxes did not benefit religious organizations

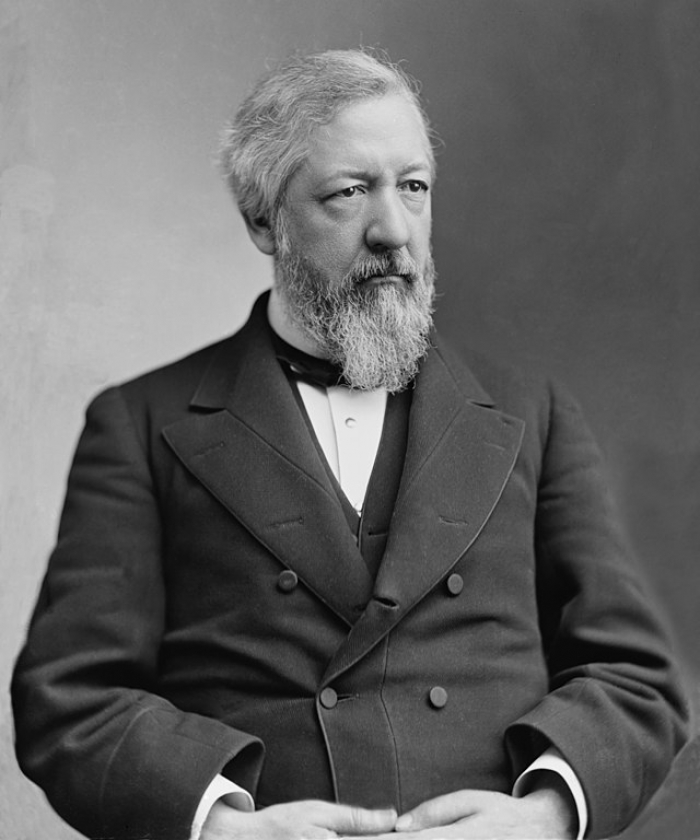

The amendments were named for James Gillespie Blaine of Maine, the Republican minority leader in the House of Representatives during the 1870s. Blaine sought to alter and expand the First Amendment as follows: ”No state shall make any law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; and no money raised by taxation in any state for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefor, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or lands so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations.”

Congress required states to add Blaine amendments to constitutions

The amendment easily passed in the House of Representatives but narrowly failed in the Senate. Many states, however, added similar amendments to their constitutions, and some had previously done so in response to Congress passing a law in 1875 requiring new states to put Blaine-type amendments in their constitutions.

Catholics tried to obtain educational funds to combat Protestantism in public schools

An effort by Roman Catholics to obtain a share of state educational spending for the network of parochial schools they were developing, in reaction to the overt Protestantism of public schools, served as the impetus for these measures. By the post–Civil War era, Catholics’ numbers had grown, providing them increasing political strength in those states in which they comprised significant segments of the population.

Creators and supporters of Blaine amendments were inconsistent in their espousal of strict separation of church and state. While their opposition to government spending on parochial schools had the effect of making their state constitutions more explicit than the U.S. Constitution in prohibiting state support of religion establishments, they saw no conflict with simultaneously supporting Protestant practices in public schools as well as state legislatures and other public settings.

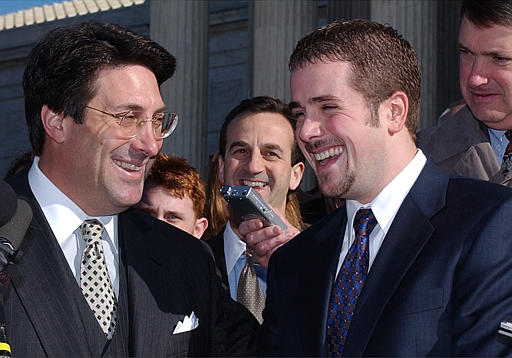

The Supreme Court reviewed a challenge to a Blaine-type law in Locke v. Davey (2004). The Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the state of Washington and its law prohibiting the use of state funds in sectarian schools. Joshua Davey had claimed that his right to free exercise of religion was infringed by the state of Washington’s refusal, based on a passage in the state’s constitution, to let him participate in its Promise Scholarship Program to pursue a theology degree. In this photo, attorney Jay Sekulow, left, and Davey talk to reporters outside the U. S. Supreme Court in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 2, 2003, following oral arguments (AP Photo/Dennis Cook, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Blaine amendments have faced modern challenges

In the 1930s and 1940s, some states began to view Catholic schools as performing a public service and offered to pay for bus transportation to them. When such funding was challenged on the basis of Blaine amendments, efforts arose to abolish these amendments and to allow for spending on school transportation. Attempts to replace the amendments or to omit them from new state constitutions, however, often met with public resistance.

In the early 21st century, many state constitutions still had Blaine amendments, which became an issue as the voucher movement gathered steam. After the Supreme Court’s ruling in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002) appeared to remove First Amendment obstacles to voucher programs, pro-voucher forces turned their attention to rescinding Blaine amendments, which they viewed as the biggest remaining obstacle to state voucher legislation allowing students to use government funds to attend sectarian schools.

They also sought to challenge Blaine amendments in the federal courts as a violation of the Constitution because of their history as products of religious bigotry and anti-Catholicism.

Court ruled in favor of Blaine-type law in Washington

This situation provided the impetus for Locke v. Davey (2004), in which the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the state of Washington and its law prohibiting the use of state funds in sectarian schools. Joshua Davey had claimed that his right to free exercise of religion was infringed by the state of Washington’s refusal, based on a passage in the state’s constitution, to let him participate in its Promise Scholarship Program to pursue a theology degree.

The relevant passage in the Washington constitution, article 9, section 4, reads, “All schools maintained or supported wholly or in part by the public funds shall be forever free from sectarian control or influence.”

The American Center for Law and Justice represented Davey and urged the Supreme Court not to grant certiorari in the case but to let stand the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling until other Blaine amendment cases were decided in the lower courts; other pro-voucher groups, however, wanted the case to be heard quickly in the hope that a ruling would, in effect, make all Blaine amendments unconstitutional.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, in a footnote to his majority opinion, said that neither Davey nor amicus briefs made a credible argument that the Washington constitution’s relevant provision was a product of religious bigotry and “accordingly the Blaine Amendment’s history is simply not before us.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Jane G. Rainey is a professor emeritus of political science at Eastern Kentucky University. She specializes in politics and religion in the United States. She speaks to civic and church groups on First Amendment establishment clause issues and the role of churches and faith-based groups in influencing public policy.