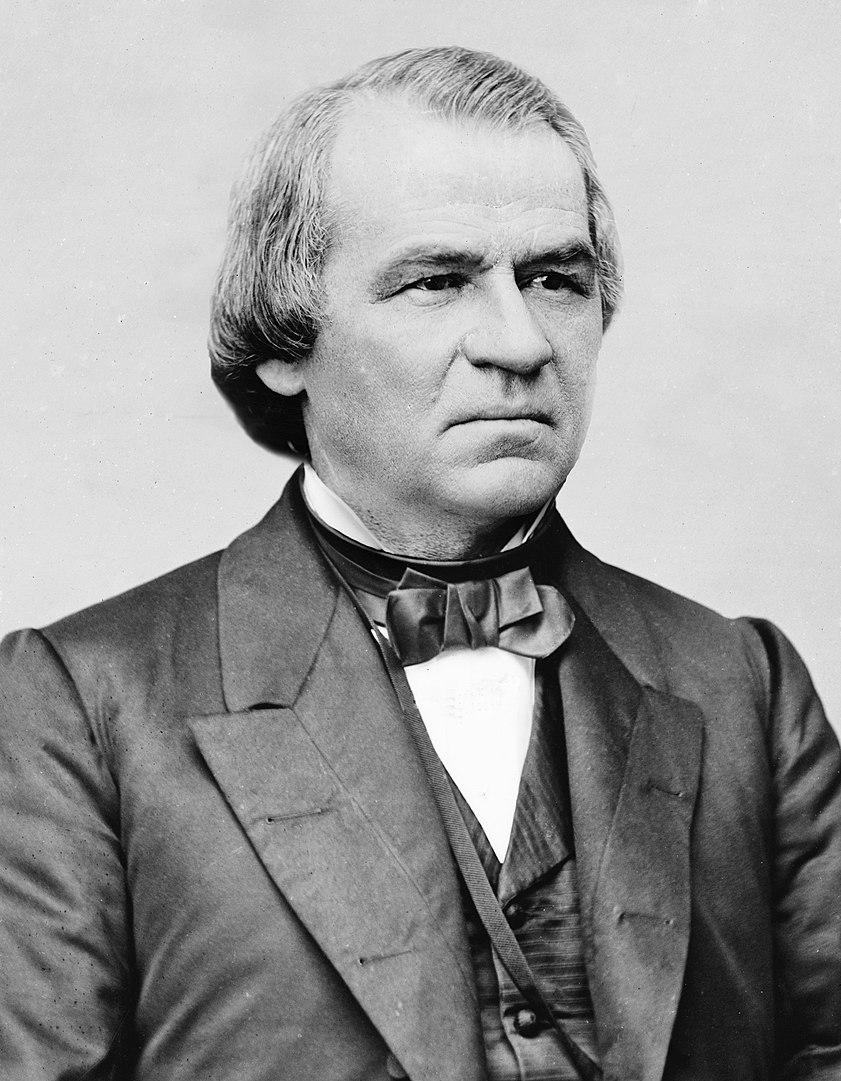

Andrew Johnson (1808-1875) was born in North Carolina but spent most of his life in Tennessee. Lacking formal education, he began his working life as a tailor and was taught by his wife to read and write.

A Jacksonian Democrat, he served as a town alderman, as mayor of Greeneville, Tennessee, in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1843 to 1853, as governor of Tennessee from 1853 to 1857, and as a U.S. senator from 1857 to 1862. Johnson supported the Union cause and was the only U.S. senator from the South to continue in the Senate after their states seceded (Tennessee was the last state to do so). Abraham Lincoln appointed him to be the military governor of the state in 1862 after the Union gained control of the state.

As military governor while the Civil War continued, Johnson, consistent with other actions restricting First Amendment freedoms during this era, arrested community leaders, including ministers, who were expressing pro-Confederate sentiments, and jailed those who refused to take an oath of loyalty to the Union (Wedge 2013, iii).

Chosen to balance the 1864 presidential ticket, Johnson then served briefly as vice president under Abraham Lincoln. When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, Johnson became president and served out the remainder of Lincoln’s term ending in 1869.

Johnson became president at a time when the wounds of war had yet to heal. His tendency to speak off the cuff, sometimes while inebriated, in highly vitriolic language against his political opponents, and his desire to accept Southern states back in the union without reconstructing their laws to guarantee basic liberties to African Americans, led to increasing conflict with Congress.

Congress overrode Johnson’s vetoes of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill of 1866 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Johnson also unsuccessfully opposed adoption of the 14th Amendment, which gave citizenship to former slaves. After he fired a member of his cabinet contrary to the Tenure of Office Act, which is now recognized as imposing an unconstitutional restraint on the president’s removal power, the House of Representatives impeached him (he became the first of only three presidents to have been so charged). He escaped conviction and removal in the U.S. Senate by a single vote.

Johnson speaks of freedom of conscience

In Johnson’s First Annual Message to Congress on Dec. 4, 1865, he stressed both states’ rights and the perpetuity of the Union. He observed that although “ancient republic absorbed the individual in the state — prescribed his religion and controlled his activity, the U.S. system “rests on the assertion of the equal right of every man to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, to freedom of conscience, to the culture and exercise of all his faculties.”

Commenting later in his speech on what made America attractive to immigrants, Johnson observed:

“Here religion, released from political connection with the civil government, refused to subserve the craft of statesmen, and becomes in its independence the spiritual life of the people. Here toleration is extended to every opinion, in the quiet certainty that truth needs only a fair field to secure the victory. Here the human mind goes forth unshackled in the pursuit of science, to collect stores of knowledge and acquire an ever-increasing mastery over the forces of nature.”

Court during Johnson’s period viewed First Amendment as limiting only national government

Johnson was president at a time when the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted the First Amendment, in accord with the decision in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), as a limitation only upon the national government and not upon the states.

Some supporters of the 14th Amendment, which Johnson had opposed, hoped that one or more of its provisions for equal protection of the law, due process of law, and guarantees for national privileges and immunities might serve as a vehicle for applying such rights to the states, but the U.S. Supreme Court would largely stymie this interpretation until, in Gitlow v. New York (1925), it finally ruled that the amendment included the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and press, with others to follow.

During Johnson’s tenure as president, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Milligan (1866) that military courts had no right to try civilians when civilian courts remained in operation. In a decision in Regina v. Hicklin (1868), an English court articulated a test for obscenity that relied on “whether the tendency of the matter is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort might fall.” U.S. Courts would apply this test for decades before deciding that it was incompatible with First Amendment freedoms.

Johnson blocked from making appointments to Supreme Court

Although a vacancy arose on the Supreme Court when John Catron died during Johnson’s presidency, Congress reduced the size of the court rather than give him the chance to make the appointment, so he did not appoint anyone to the Court during his tenure.

Johnson was succeeded in office by Ulysses S. Grant, who, unlike Johnson, favored the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, granting the right to vote to African American men. Grant was able to make four appointments to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1874, The Tennessee legislature selected Johnson to serve in the U.S. Senate, but he died within months of assuming office.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 15, 2023.