Roger Nash Baldwin (1884–1981) founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920 and served as its executive director from 1920 to 1950.

Baldwin was born in Wellesley Hills, Massachusetts, into an affluent and socially active New England family. His uncle William Henry served as director of the National Child Labor Committee, and his aunt Ruth Standish Bowles helped found the National Urban League.

Baldwin became active in social work, reform movements early in his career

While at Harvard College, Baldwin volunteered as an instructor for adult education classes for low-income workers, thereby launching his social work. He then headed west to Missouri, accepting, on the advice of family friend Louis D. Brandeis, an offer from Washington University to teach sociology and to work at a settlement house in St. Louis.

There, he soon became prominent in the social work community and active in leading reform movements such as the settlement house movement, African American rights groups, and good government leagues.

Baldwin’s group investigated by government for work with conscientious objectors

During World War I, Baldwin directed the American Union Against Militarism (AUAM) in St. Louis and later served as AUAM secretary in New York.

The government investigated the group for its work in behalf of conscientious objectors. In 1918 Baldwin himself was called up for military service, but, to demonstrate his solidarity with wartime resisters, he refused to serve and was sentenced to a year in prison. After his release, he married prominent journalist and feminist Madeleine Z. Doty, whom he later divorced.

Baldwin started American Civil Liberties Union

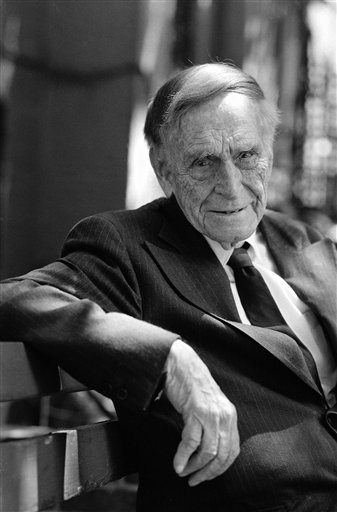

A religious pacifist, Rev. Francis Hall, extreme right, sits before a test tribunal for conscientious objectors in New York in 1940. From left: Roger Baldwin, director of the American Civil Liberties Union, Evan W. Thomas, chairman of the New York War Resisters League, and Herman Reissig. Baldwin founded the ACLU in 1920. (AP Photo/Anthony Camerano, with permission from the Associated Press)

In 1917 Baldwin founded the Civil Liberties Bureau as a branch of the AUAM. By 1920 the bureau had grown into an independent organization. Now known as the American Civil Liberties Union, the group became the country’s first national civil liberties organization.

Under Baldwin’s 30-year tenure as the first executive director of the ACLU, the organization quickly earned a reputation for defending the civil liberties of some of the most controversial members of society. In some of its earliest cases, the ACLU provided legal support for anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and in the Scopes monkey trial (Scopes v. State [Tenn. 1925], [Tenn. 1927]) it defended the right to teach evolution.

ACLU under Baldwin leadership spurred landmark First Amendment cases

Baldwin also led the ACLU as it spurred many landmark First Amendment cases, including the extension of First Amendment prohibitions against censorship to the states in the Supreme Court cases Gitlow v. New York (1925) and Stromberg v. California (1931), as well as the victory over attempts to censor James Joyce’s Ulysses in the Second Circuit case United States v. One Book Entitled “Ulysses” (1933).

Outside his work at the ACLU, Baldwin was criticized for his involvement in socialist causes and his praise for the Soviet Union in his book Liberty under the Soviets (1928).

Baldwin was awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom

However, after the Soviets signed the 1939 German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact with the Nazis, Baldwin lost faith in communism, and his later work called for human rights in Soviet bloc countries.

After World War II, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander for the Allied Powers, asked Baldwin to help Japan and Korea develop civil liberties protections. Several months before Baldwin’s death in 1981, President Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

This article was originally published in 2009. Julie Lantrip is the Honors Program Director at Tarrant County College – Northwest Campus.