Censorship occurs when individuals or groups try to prevent others from saying, printing, or depicting words and images.

Censors seek to limit freedom of thought and expression by restricting spoken words, printed matter, symbolic messages, freedom of association, books, art, music, movies, television programs, and Internet sites. When the government engages in censorship, First Amendment freedoms are implicated.

Private actors — for example, corporations that own radio stations — also can engage in forms of censorship, but this presents no First Amendment implications as no governmental, or state, action is involved.

Various groups have banned or attempted to ban books since the invention of the printing press. Censored or challenged works include the Bible, The American Heritage Dictionary, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, To Kill A Mockingbird, and the works of children’s authors J. K. Rowling and Judy Blume.

The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and press, integral elements of democracy. Since Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court has applied the First Amendment freedoms of speech and press to the states through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

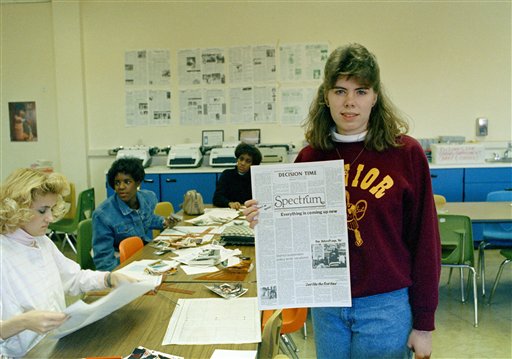

The Supreme Court ruled in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) that school officials have broad power of censorship over student newspapers. In this photo, Tammy Hawkins, editor of the Hazelwood East High School newspaper, Spectrum holds a copy of the paper, Jan. 14, 1988. (AP Photo/James A. Finley, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Not all speech is protected by the First Amendment

Freedom of speech and press are not, however, absolute. Over time, the Supreme Court has established guidelines, or tests, for defining what constitutes protected and unprotected speech. Among them are:

- the bad tendency test, established in Abrams v. United States (1919),

- the clear and present danger test from Schenck v. United States (1919),

- the preferred freedoms doctrine of Jones v. City of Opelika (1943), and

- the strict scrutiny, or compelling state interest, test set out in Korematsu v. United States (1944).

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. offered the classic example of the line between protected and unprotected speech in Schenck when he observed that shouting “Fire!” in a theater where there is none is not protected speech. Categories of unprotected speech also include:

- libel and slander,

- “fighting words,”

- obscenity, and

- sedition.

Libel and slander when it comes to public officials

Determining when defamatory words may be censored has proved to be difficult for the Court, which has allowed greater freedom in remarks made about public figures than those concerning private individuals.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court held that words can be libelous (written) or slanderous (spoken) in the case of public officials only if they involve actual malice or publication with knowledge of falsehood or reckless disregard for the truth. Lampooning has generally been protected by the Court.

In Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988), for example, the Court held that the magazine had not slandered Rev. Jerry Falwell by publishing an outrageous “advertisement” containing a caricature of him because it was presented as parody rather than truth.

On the issue of press freedoms, the Court has been reluctant to censor publication of even previously classified materials, as in New York Times v. United States (1971) — the Pentagon Papers case — unless the government can provide an overwhelming reason for such prior restraint.

The Court has accepted some censorship of the press when it interferes with the right to a fair trial, as exhibited in Estes v. Texas (1965) and Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966), but the Court has been reluctant to uphold gag orders, as in the case of Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart (1976).

In general, rap and hard-core rock-n-roll have faced more censorship than other types of music. In this photo, rap artists DJ Jazzy Jeff (Jeff Townes), left, and The Fresh Prince (Will Smith) are seen backstage at the American Music Awards ceremony in Los Angeles, Calif., Monday, January 31, 1989, after winning in the category Favorite Rap Artist and Favorite Rap Album. (AP Photo/Lennox McLendon, used with permission from the Associated Press)

When words incite “breach of peace”

In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), the Supreme Court defined “fighting words” as those that “by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Racial epithets and ethnic derisions have traditionally been unprotected under the umbrella of “fighting words.”

Since the backlash against so-called political correctness, however, liberals and conservatives have fought over what derogatory words may be censored and which are protected by the First Amendment.

Determining whether something is obscene

In its early history, the Supreme Court left it to the states to determine whether materials were obscene.

Acting on its decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925) to apply the First Amendment to limit state action, the Warren Court subsequently began dealing with these issues in the 1950s on a case-by-case basis and spent hours examining material to determine obscenity.

In Miller v. California (1973), the Burger Court finally adopted a test that elaborated on the standards established in Roth v. United States (1957). Miller defines obscenity by outlining three conditions for jurors to consider:

- “(a) whether the ‘average person, applying contemporary community standards,’ would find that the work taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest;

- (b) whether the work depicts or describes in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law; and

- (c) whether the work taken as a whole lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Proposals to censor music date back to Plato’s Republic. In the 1970s, some individuals thought anti-war songs should be censored. In the 1980s, the emphasis shifted to prohibiting sexual and violent lyrics. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) also sought to fine radio stations for the broadcast of indecent speech. In general, rap and hard-core rock-n-roll have faced more censorship than other types of music. Caution must be used in this area to distinguish between governmental censorship and private censorship.

Courts have not interpreted the First Amendment rights of minors, especially in school settings, to be as broad as those of adults; their speech in school newspapers or in speaking to audiences of their peers may accordingly be censored.

Advancing technology has opened up new avenues in which access to a variety of materials, including obscenity, is open to minors, and Congress has been only partially successful in restricting such access. Parental controls on televisions and computers have provided parents and other adults with some monitoring ability, but no methods are 100 percent effective.

Censorship often increases in wartime to tamp down anti-government speech. In this 1942 photo, W. Holden White, clips items from U.S. newspapers at the Washington, D.C. headquarters of the office of censorship to determine newspaper compliance with censorship rules prescribed by the office. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Wrestling with sedition and seditious speech

In general, sedition is defined as trying to overthrow the government with intent and means to bring it about; the Supreme Court, however, has been divided over what constitutes intent and means.

In general, the government has been less tolerant of perceived sedition in times of war than in peace. The first federal attempt to censor seditious speech occurred with the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 under President John Adams.

These acts made it a federal crime to speak, write, or print criticisms of the government that were false, scandalous, or malicious. Thomas Jefferson compared the acts to witch hunts and pardoned those convicted under the statues when he succeeded Adams.

Laws attempting to reduce anti-government speech

During World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, and the Court spent years dealing with the aftermath.

In 1919 in Schenck, the government charged that encouraging draftees not to report for duty in World War I constituted sedition. In this case, the court held that Schenck’s actions were, indeed, seditious because, in the words of Justice Holmes, they constituted a “clear and present danger” of a “substantive evil,” defined as attempting to overthrow the government, inciting riots, and destruction of life and property.

In the 1940s and 1950s, World War II and the rise of communism produced new limits on speech, and McCarthyism destroyed the lives of scores of law-abiding suspected communists.

The Smith Act of 1940 and the Internal Security Act of 1950, also known as the McCarran Act, attempted to stamp out communism in the country by establishing harsh sentences for advocating the use of violence to overthrow the government and making the Communist Party of the United States illegal.

After the al-Qaida attacks of September 11, 2001, and passage of the USA Patriot Act, the United States faced new challenges to civil liberties. As a means of fighting terrorism, government agencies began to target people openly critical of the government. The arrests of individuals suspected of knowing people considered terrorists by the government was in tension with, if not violation of, the First Amendment’s freedom of association. These detainees were held without benefit of counsel and other constitutional rights.

The George W. Bush administration and the courts have battled over the issues of warrantless wiretaps, military tribunals, and suspension of various rights guaranteed by the Constitution and the Geneva Conventions, which stipulate acceptable conditions for holding prisoners of war.

Certain forms of speech are protected from censure by governments. For instance, the First Amendment protects pure speech, defined as that which is merely expressive, descriptive, or assertive. Less clearly defined are those forms of speech referred to as speech plus, that is, speech that carries an additional connotation, such as symbolic speech. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court upheld the right of middle and high school students to wear symbolic black armbands to school to protest U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In this photo, Debbie Wallace, left, and Phyllis Sweigert, 17-year-old seniors at suburban Euclid High School in Cleveland, Ohio, display armbands they wore to school in mourning for the dead in Vietnam, Dec. 10, 1965. The girls were suspended from school until Monday. (AP Photo/Julian C. Wilson, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Expressive and symbolic speech

Certain forms of speech are protected from censure by governments. For instance, the First Amendment protects pure speech, defined as that which is merely expressive, descriptive, or assertive. The Court has held that the government may not suppress speech simply because it thinks it is offensive. Even presidents are not immune from being criticized and ridiculed.

Less clearly defined are those forms of speech referred to as speech plus, that is, speech that carries an additional connotation. This includes symbolic speech, in which meanings are conveyed without words.

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court upheld the right of middle and high school students to wear black armbands to school to protest U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

One of the most controversial examples of symbolic speech has produced a series of flag desecration cases, including Spence v. Washington (1974), Texas v. Johnson (1989), and United States v. Eichman (1990).

Despite repeated attempts by Congress to make it illegal to burn or deface the flag, the Court has held that such actions are protected. Writing for the 5-4 majority in Texas v. Johnson, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. stated, “We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents.”

When speech turns into other forms of action, constitutional protections are less certain.

In R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992), the Court overturned a local hate crime statute that had been used to convict a group of boys who had burned a cross on the lawn of a black family living in a predominately white neighborhood.

The Court qualified this opinion in Virginia v. Black (2003), holding that the First Amendment did not protect such acts when their purpose was intimidation.

This article was originally published in 2009. Elizabeth Purdy, Ph.D., is an independent scholar who has published articles on subjects ranging from political science and women’s studies to economics and popular culture.