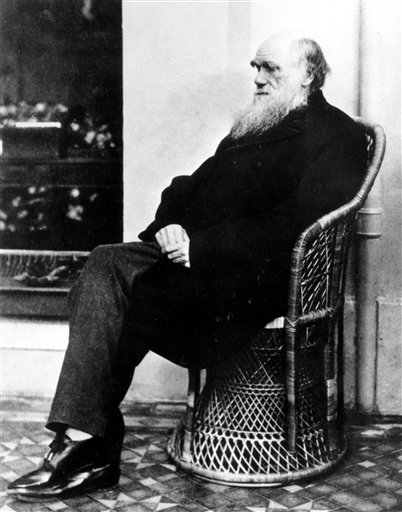

In On the Origin of Species (1859), Charles Darwin proposed that small mutations in plants and animals aggregate over generations, leading to diversity within, and eventually among, species. Later, in Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Darwin applied this theory to humans.

Teaching evolution has been at heart of many First Amendment cases

The theory remained largely unchanged until the 1940s, when scientists proposed that variations within species are passed down through organisms’ genetic code, thus making the offspring of better-suited individual plants or animals more likely to survive. The teaching of the scientific theory of evolution has been at the heart of numerous cases brought under the establishment clause, the free exercise clause, and the free speech clause of the First Amendment. Since the early part of the 20th century, those critical of evolution have attempted to ban it from public school curricula.

Evolution’s adherents agree that the diversity of species is attributable to biological processes, but they disagree about the involvement of a divine being. Although much opposition to evolution has been religiously based, many religious organizations, including the Catholic Church, many mainline Protestant denominations, and the American Jewish Congress, acknowledge that evolution can be consistent with religious faith.

In this photo, the opposing attorneys in the Scopes “monkey trial,” Clarence Darrow, left, and William Jennings Bryan, speak with each other in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925. The trial involved a teacher convicted under a Tennessee law that prohibited teaching evolution. The teacher was found guilty of violating the law. Whether the law was valid was not discussed. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Scopes monkey trial involved Tennessee’s anti-evolution law

For several decades after the publication of Descent of Man, into the early 20th century, evolution was a staple of biology textbooks and classroom instruction. About this same time, however, a Christian fundamentalist movement took root in the United States, arguing that evolution was inconsistent with the biblical six-day creation story and should not be taught in schools. Twenty state legislatures considered prohibiting science teachers from instructing their students about evolution. Six states (mostly in the Deep South) adopted such laws.

One of these laws, Tennessee’s, gave rise to what is still known as the Scopes monkey trial. Knowing that he would be arrested, John Scopes taught evolution in a high school science class. Eventually, Scopes was convicted and fined $100, but his conviction was overturned on a technicality. Although public discussion of this trial has always focused on the propriety of teaching evolution, the legal issue in State v. Scopes (1925) was the narrow one of whether the statute was violated, and appellate challenges to the statute’s validity were dismissed summarily (Scopes v. State [Tenn. 1927]). After the Scopes decision textbook publishers minimized the coverage of evolution until the late 1950s and early 1960s.

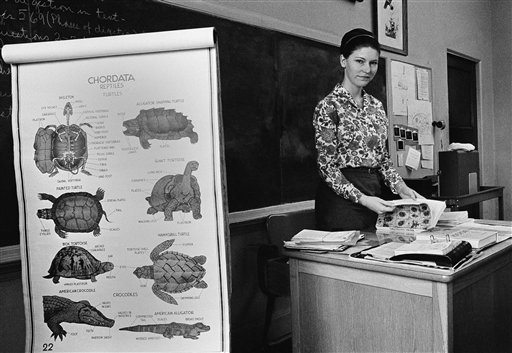

The establishment clause, which requires a degree of separation between church and state, has been the most common legal basis for challenges to state attempts to restrict evolution-related instruction. By 1968, when Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) made its way to the Supreme Court, only two states maintained their Scopes-like anti-evolution statutes: Arkansas and Mississippi (Tennessee rescinded its statute in 1967). In Epperson, the Supreme Court invalidated the Arkansas statute as a violation of the establishment clause.

‘Creation science’ contended with evolution

Evolution’s detractors then began recasting creationism as “creation science” and asking that it be treated as evolution’s equal — when one concept was taught, the other would be, too. In McLean v. Arkansas (1982), the first test of this so-called balanced treatment approach, a federal district judge held that “creation science” was not science and that the state lacked the requisite secular purpose when enacting the statute.

The Supreme Court confronted the same issue a few years later, holding in Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) that teaching “creation science” endorsed religion and also undermined comprehensive science instruction.

More recently, school districts have included disclaimers of evolution at the beginning of that unit in science classes. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected an oral disclaimer in Herb Freiler v. Tangipahoa Parish Board of Education (1999). Similarly, a district court in Georgia rejected a sticker placed inside the science textbook in Selman v. Cobb County School District (2005), but that decision was vacated and remanded on appeal in 2006 for further factual findings.

‘Intelligent design’ arose as an alternative to evolution and creation science

A disclaimer also was at issue in one recent battle over “intelligent design,” a concept consisting of two main arguments: Various organisms in their most basic forms were irreducibly complex and could not have evolved from simpler organisms, and the odds of current systems and organisms randomly evolving to exist as they do today are prohibitively low.

Both approaches rely on the existence and involvement of an unnamed “intelligent agent” to account for the current diversity of species. The vast majority of scientists reject intelligent design’s claims in favor of evolution.

In October 2004, a school district in Dover, Pa., voted to inform students about intelligent design by reading a statement in biology class and providing reference copies of the book Of Pandas and People. The American Civil Liberties Union challenged this policy in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District (2005); after a six-week trial in a federal district court in Pennsylvania, which included the testimony of numerous experts, the judge noted the scientific community’s overwhelming rejection of intelligent design and concluded that intelligent design is not science.

In this photo, biology teacher Susan Epperson, who challenged Arkansas’ ban on the teaching of the theory of evolution, is shown at her desk in Little Rock Arkansas in 1966.. In Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), the Supreme Court invalidated the Arkansas statute as a violation of the establishment clause. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

First Amendment arguments against teaching evolution have failed

Whereas the establishment clause focuses broadly on the purpose and effect of government action, the free exercise clause focuses on individuals’ expression of their own religious beliefs. Attempts to challenge evolution instruction as a free exercise violation have been unsuccessful.

For example, in Seagraves v. State of California (1981), the Sacramento Superior Court rejected the claim that a school’s teaching of evolution violated the free exercise rights of a parent and his children whose religious beliefs conflicted with evolution; important to the case was the state’s policy of not teaching evolution “dogmatically.”

In another case, Peloza v. Capistrano Unified School District (1994), the 9th Circuit determined that a teacher’s free exercise rights were not violated when he was required to teach evolution in science class and not criticize evolution outside of class. The court noted the school district’s strong interest in avoiding an establishment clause violation.

Teachers have also unsuccessfully challenged mandatory evolution instruction as a violation of their own free speech rights.

Specifically, in Webster v. New Lenox School District (1990), the 7th Circuit held that a teacher could be prohibited from teaching creation science because doing so would amount to the promotion of religion. A state appellate court in Minnesota reached a similar decision in LeVake v. Independent School District (2001).

This article was originally published in 2009. Kristine Bowman is a Professor of Law at Michigan State University.