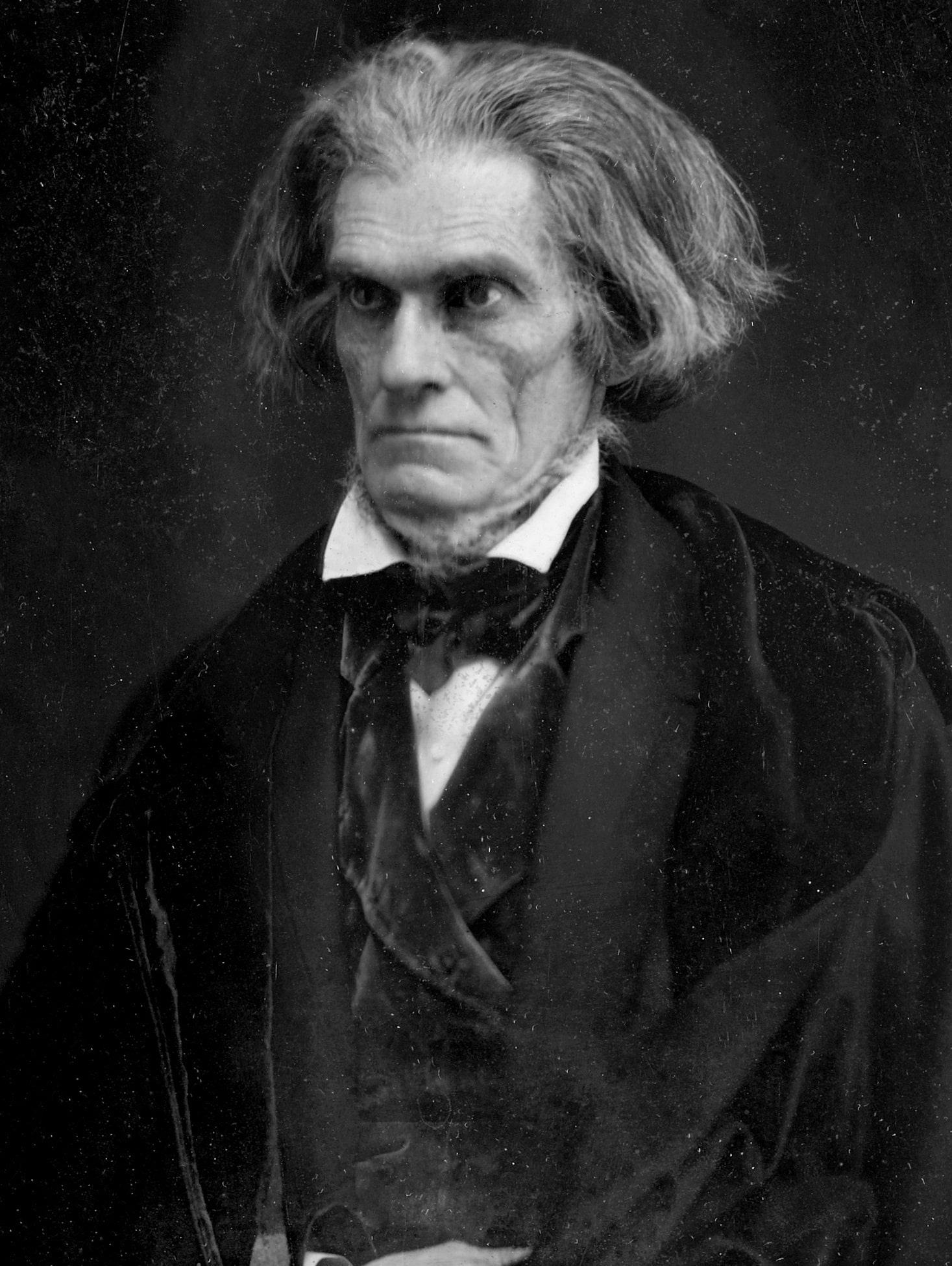

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) was a prominent 19th century South Carolina politician who became a major figure in efforts to keep the Senate from considering petitions to eliminate slavery and to exclude abolitionist literature from the mails.

Calhoun served as a U.S. senator from South Carolina from 1832-1843 and from 1845 to 1850.

He also had been vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, Secretary of War under President James Monroe and Secretary of State under both John Tyler and James K. Polk. Despite his hopes, he was never nominated for president by a major party.

Calhoun is often identified with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay as one of the greatest U.S. senators of the 19th century. Beginning his political life as a strong nationalist, Calhoun became the leading defender of strict constitutional construction and states’ rights as slavery began to divide the nation.

Calhoun’s efforts to limit Senate debate on abolition of slavery

Because Calhoun believed that the Constitution had affirmatively approved of slavery through the three-fifths clause, the fugitive slave clause and the slave importation clause, he thought the issue had been settled and did not warrant discussion and debate despite the First Amendment.

He was particularly adamant about closing off discussion on limiting slavery within new territories and states and about those who called for complete abolition of slavery.

Calhoun was thus on the forefront of unsuccessful efforts to keep the Senate from joining the House from considering petitions to eliminate slavery. He also favored efforts to remove abolitionist literature from the mails.

On Feb. 6, 1837, Calhoun gave a major speech on the floor of the Senate opposing the reception of abolitionist petitions, which he thought would be the opening wedge for the destruction of slavery and the southern way of life.

Calhoun thought debating abolitionist petitions would be ‘fatal’

In this speech, he argued that “any “concession or compromise” on this issue would be fatal. He observed that abolitionism “will continue to rise and spread, unless prompt and efficient measures to stay its progress be adopted.”

"Consent to receive these insulting petitions, and the next demand will be that they be referred to a committee in order that they may be deliberated and acted upon. . . .

As widely as this incendiary spirit [of abolition] has spread, it has not yet infected this body, or the great mass of the intelligent and business portion of the North; but unless it be speedily stopped, it will spread and work upwards till it brings the two great sections of the Union into deadly conflict."

Perhaps reflecting his own fears of the power of speech and of public opinion, he recognized that abolitionism has “already “taken possession of the pulpit, of the school and, to a considerable extent, of the press; those great instruments by which the mind of the rising generation will be formed.”

He feared that sentiment in the North would gradually turn away from accepting slavery as long as it was not in their states and begin seeking its complete abolition in the South. He thought that current Southern sympathizers “will be succeeded by those who will have been taught to hate the people and institutions of nearly one-half of this Union, with a hatred deadlier than one hostile nation every entertained toward another.”

A scholar of political thought in the old South observes that “In the decline of free thought and speech below the Potomac, the significance of Calhoun lies primarily in his role as an agitator. He was the chief of a group of politicians and sectional statesmen who exploited the slavery issue and created stereotypes in the minds of the Southern people that produced intolerance” (Eaton 1940, 158).

In time, of course, the Civil War resulted in the adoption of the 13th Amendment, which eliminated involuntary servitude based on race.

Calhoun’s philosophy in other areas

Calhoun fell out with President Andrew Jackson in part because of Calhoun’s opposition to the Tariff Act of 1828, which Calhoun opposed in the South Carolina Exposition and Protest. He called the tariff the “Tariff of Abominations” because he thought it benefited northern industrial and commercial interests over southern agricultural ones.

Calhoun authored A Disquisition on Government and a Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States. In these and other works, Calhoun defended states’ rights and slavery. Because he feared northern intentions, Calhoun made every effort to resist increasing free state representation in Congress by advocating the admission of slavery into all U.S. territories, and he opposed the strengthening of federal powers that might one day be employed to eliminate slavery.

In the process of articulating his theories, Calhoun formulated a doctrine of concurrent majorities. It was designed to assure that all major interests wielding power (especially the slave power) had a veto over major governmental initiatives, rather than leaving the future determination of such matters to simple numerical majorities, which might in time be able to use the constitutional amending process to eliminate slavery.

Building upon the doctrine of interposition that Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had articulated in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, Calhoun argued that individual states were parties to a compact and had the right to nullify federal laws that they believed to be incompatible with the Constitution. In such cases, he argued that the national government could not act without a new amendment specifically affirming its powers in such an area. Even then, he reserved the right of the states to determine whether such an amendment fell “fairly within the scope of the amending power” (Vile 1992, 86).

In time, this philosophy, in turn, developed into the idea (attempted in the Civil War) that states that were no longer satisfied with the constitutional arrangement had the right to secede from the Union.

Whereas most prominent southern leaders had previously defended slavery as a necessary evil for the support of their economy, Calhoun shifted this focus by arguing that it was a positive good, not only for the slaveowners, but for the slaves themselves. Specifically denying the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,”, he believed that the white race was superior to the black race, whose members he thought were better provided for under slavery than white northern factory workers. Calhoun also believe that the feelings between the two races were so hostile that if southern slaves were freed, they would seek to enslave their former masters.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.