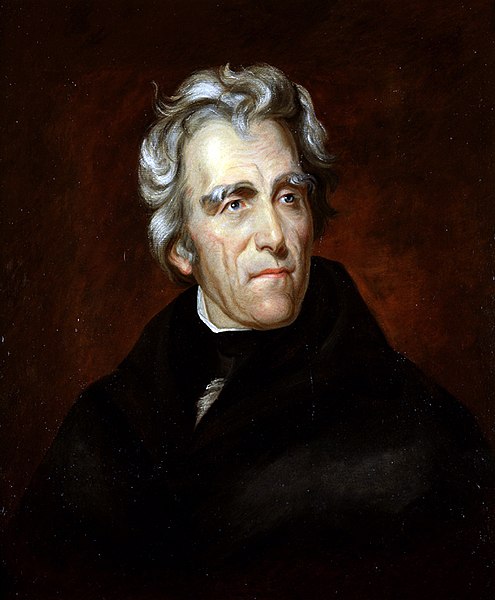

Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), who served as president from 1829 to 1837, was one of the most consequential presidents in U.S. history. Born in North Carolina, Jackson spent most of his life in Tennessee where he served as a justice on the state supreme court from 1798 to 1804 and as a U.S. senator from 1823 to 1825.

Although he read law, he gained his primary reputation as a military figure fighting against Native Americans and winning a major battle in New Orleans in January 1816 at the end of the War of 1812.

Under Jackson, the nation moved closer to universal white male suffrage and the Democrat Party widened its appeal to common citizens and began adopting many of the trappings that would epitomize popular politics throughout the 19th century. As a president who was elected by people throughout the United States, Jackson considered himself to be the “tribune of the people.” As a white southerner, Jackson owned slaves and defended the institution. He was also determined to remove Native Americans from eastern states to the West, often defying judicial decisions in the process.

Jackson opposed idea that states could nullify federal laws

Although Jackson sometimes interpreted the Constitution strictly (thus vetoing appropriations for a federal road) and generally favored states’ rights, he strongly opposed the doctrine that states had the right to nullify federal laws. He took a strong unionist stance against John C. Calhoun and other southerners who had advocated opposition to national tariff policies.

Jackson was known for his extension of patronage, known as the “spoils system,” whereby he rewarded his supporters with governmental jobs. Although this made the government more politically responsive, it also bred corruption and inefficiency. In time, the U.S. adopted a civil service system to reward education and experience.

Even though the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of the national bank, Jackson associated the bank with special privilege and removed deposits, causing it to fail. He argued that as head of a coordinate branch of government, his interpretations of the Constitution were equal to that of the judiciary. He was censured by the U.S. Senate, although this censure was later repealed.

First Amendment issues

Jackson supported separation of ‘sacred’ and ‘secular’ concerns

As a delegate who helped write Tennessee’s Constitution in 1796, Jackson had opposed a provision that would have required a religious oath for public office, which the U.S. Constitution prohibited for national office. As president, Jackson refused to call for a national day of prayer and fasting to halt a cholera epidemic because he believed that the Constitution “carefully separated sacred from secular concerns” (Smith 2015, 144). When asked to endorse an organization seeking to establish Sunday schools in the West, Jackson indicated that he could only provide such an endorsement if it did not prefer one denomination over another (Smith 2015, 145).

In 1833, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed in Barron v. Baltimore that the Bill of Rights (including the provisions of the First Amendment) applied only to the national government and not to the states. Later conclusions applying the Bill of Rights to the states came from future Supreme Court interpretations of the 14th Amendment that was adopted in 1868 after the U.S. Civil War.

Jackson repressed speech during War of 1812

One of Jackson’s most repressive actions respecting freedom of speech occurred in 1814, prior to his presidency. As he prepared to battle British troops during the War of 1812, he took the unprecedented step of declaring martial law in New Orleans. Moreover, he refused to lift this order after his impressive victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans, even after receiving news that the Treaty of Ghent, which had actually been signed prior to the battle, had brought the war to an end.

Jackson attempted to impose prior restraint on publication of the announcement of the treaty, but the Louisiana Gazette published the notice anyway. In doing so, it announced that “Every man may read for himself, and think for himself; (Thank God! Our thoughts are as yet unshackled!!) but as we have been officially informed that the city of New-Orleans is a camp, our readers must not expect us to take the liberty of expressing our opinions as we might in a free city” (Quoted in Turley 2024, 128).

State senator Louis Louaillier, who had previously supported Jackson’s efforts against the British, subsequently wrote an anonymous letter that appeared in the Louisiana Courier, which called for the restoration of civilian rule and civil liberties. When Jackson traced it to Louaillier, Jackson accused him of sedition and had him arrested as a spy. Jackson also ordered the arrest of the judge who issued a writ of habeas corpus on Louaillier’s behalf.

Even though he was a civilian, Louaillier was tried by a military court, which, however, acquitted him. Louaillier, whom Jackson had sought to banish from the city, subsequently sued and secured a $1,000 fine against Jackson.

Jackson advocated censoring mail of anti-slavery literature

Jackson reacted negatively to press attacks on him and his policies. He was strongly opposed to The Cherokee Phoenix, in which John Ross, the head of the Cherokees and his allies, had expressed opposition to Jackson’s Indian Removal policies. Jackson’s followers destroyed this press as it was being transported from Georgia to Tennessee.

Jackson was also deeply troubled by the use of the mail to distribute anti-slavery literature in the South, which had led to riots by slavery supporters. In his 1835 annual message to Congress, Jackson thus observed that:

I must also invite your attention to the painful excitement produced in the South by attempts to circulate through the mails inflammatory appeals addressed to the passions of the slaves. In prints and in various sorts of publications, calculated to stimulate them to insurrection and to produce all the horrors of a service war. There is doubtless no respectable portion of our countrymen who can be so far misled as to feel any other sentiment than that of indignant regret at conduct so destructive of the harmony and peace of the country, and so repugnant to the principles of our national compact and to the dictates of humanity and religion.

Jackson went on to indicate that it would be “proper for Congress to take such measures as will prevent the Post-Office Department, which was designed to foster an amicable intercourse and correspondence between all the members of the Confederacy, from being used as an instrument of the opposite character.”

Although Congress did not adopt such legislation, postmasters whom Jackson appointed often acted as censors even though it does not appear that the abolitionist literature was particularly effective, especially since most slaves to whom it was directed were illiterate. Congress did adopt “gag rules” suppressing discussion of anti-slavery petitions, which John Quincy Adams vehemently opposed.

Jackson's Supreme Court appointee issued Dred Scott opinion

Jackson appointed six justices to the U.S. Supreme Court, the most consequential of whom was Roger Taney, who had served as his Secretary of the Treasury and who would later issue the decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) declaring that Blacks were not and could not become U.S. citizens.

Jackson was succeeded in office by Martin Van Buren. James K. Polk would later continue Jackson’s political legacy. Many commentators have further associated Jackson’s populist style with that of President Donald Trump.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 8, 2023.