The Declaration of Independence, formally adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, announced the United States’ independence from Britain and enumerated to “a candid World” the reasons necessitating this separation. Today the Declaration stands as the best-known document of the American founding, describing not only the U.S. origin, but also its goals and values.

The 13 American colonies that would become the United States had been at odds with Great Britain, since the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. After that conflict, in which British and American colonists had fought side by side, the British Parliament had reversed its previous policy of “benign neglect” toward the colonies and attempted to levy direct taxes upon them and quartered soldiers in their midst

Even after fighting broke out in Massachusetts in April of 1775 between colonists and the Crown, many colonists still hoped for reconciliation. In January of 1776, Thomas Paine, a recent immigrant from England, wrote a powerful essay entitled Common Sense, in which he critiqued the institution of kingship and the process of hereditary succession and persuasively argued that it was time for the colonies to declare their independence.

As delegates from the colonies met in the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced three resolutions on June 7, 1776. The first proposed:

“That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

The second and third resolutions cast light on one of the purposes of the Declaration (that of securing foreign allies to help defeat Britain) and one of its consequences (the need for a replacement government). These resolutions respectively proposed: “That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign alliances,” and “That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respectively Colonies for their consideration and approbation.”

Congress, which appointed separate committees to deal with each of these resolutions, heeded the first on July 2 by officially declaring independence. Two days later on July 4, 1776, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence

The words in the second paragraph are the most inspirational and the most quoted. They assert the “self-evident” truths “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The document further affirmed “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” It also supported “the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it [government] and to institute new Government , , , to effect their Safety and Happiness,”

Declaration paved way for First Amendment rights

The Declaration’s indictments against King George III, which resemble a legal brief, show a vigorous exercise of freedom of speech and press while demonstrating that governments that are not responsive to peaceful expressions of sentiments may face the prospect of revolution.

By using the document to express frustration with rebuffs received to previous petitions to the king(such as the Olive Branch Petition of the previous year), the founders paved the way for later recognition of the right of petition, which is contained within the First Amendment.

The Declaration contains four references to God, whom it identifies as “Nature’s God,” “Creator,” “Supreme Judge of the world,” and “divine Providence.” The last two of these were added during congressional debates over the document. These mentions foreshadowed similar references, most of which have been generic rather than specifically Christian, in future political speeches and documents (albeit not the U.S. Constitution) despite the later First Amendment prohibition of an “establishment” of religion.

Thomas Jefferson chosen to write Declaration

In June 1776 the Continental Congress appointed John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson to the committee that would write the Declaration.

Although he was only 33 at the time, Jefferson, a Virginia-born lawyer and future U.S. president, was chosen by his fellow members to write the initial draft, largely due to his rhetorical skills. In 1774, he had published A Summary View of the Rights of British America. Although Jefferson claimed that he did not refer to any books or pamphlets while drafting the Declaration, and that his goal was that of providing “an expression of the American mind,” the document bears the clear marks of previous charters of civil liberties and limited government, such as the Magna Carta of 1218, 1628 Petition of Right, the 1689 English Bill of Rights, and the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights, the latter of which had been chiefly written by Virginia's George Mason.

Franklin and Adams both made some minor changes to Jefferson’s draft, which was then extensively debated and revised by the Second Continental Congress. The Congress deleted a long section accusing the king of being responsible for slavery in America, perhaps in part because they recognized that they had no immediate plans of their own to abolish this nefarious institution.

Authors of Declaration risked punishment for seditious libel

The heart of the Declaration lies in the 27 separate indictments against George III, whom the founders label a tyrant unfit to rule over a free people. In making such accusations, the authors risked punishment for what the British considered a form of seditious libel and even for treason, which was considered to be a capital offense. Although the attribution may be apocryphal, Franklin has long been quoted as saying that, after signing the Document, its signatories must either “all hang together,” or they would “hang separately” from British nooses.

Although the document, which was intended to rally both national and international support, is framed in terms of the rights of men, the charges list specific abuses or violations of British statutory or constitutional law. Because the colonists had long maintained that the British Parliament had no power to tax them without their consent, the Declaration directed its primary attacks against the king (“He has”), only indirectly blaming Parliament as when accusing the king of having “combined with others." Some charges are articulated in broad language, such as the charge that the king refused to assent to laws beneficial to the public interest of the colonies.

Others address more parochial concerns; Adams, for example, likely inserted the accusation against the Crown for moving legislatures to uncomfortable and distant places, a reference to the relocation of the Massachusetts legislature from Boston to Cambridge, four miles away. Although Jefferson had phrased the philosophy of the Declaration in terms of the rights of mankind, his specific charges against the king are based upon the legal customs and traditions accepted by the Crown and Parliament

Somewhat ironically, therefore, only as British subjects did the Declaration’s signers have the authority to declare their confederation with Britain broken, and to bring into existence their new identities as Americans.

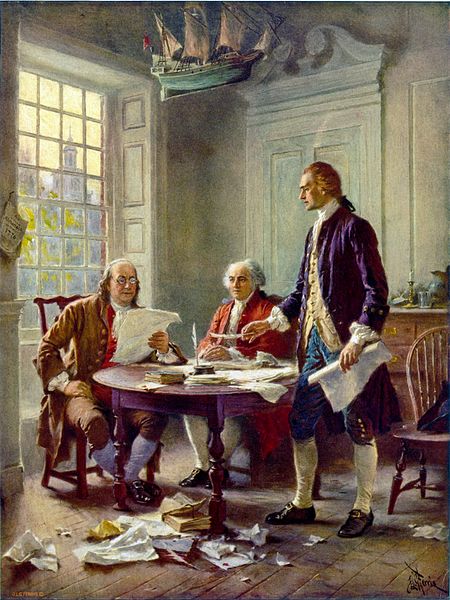

The heart of the Declaration lies in the 27 separate indictments against George III, whom the founders label a tyrant unfit to rule over a free people. In making such accusations, the authors risked punishment for what the British considered a form of seditious libel or even treason. (Thomas Jefferson (right), Benjamin Franklin (left), and John Adams (center) meet at Jefferson’s lodgings, on the corner of Seventh and High (Market) streets in Philadelphia, to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence, image via Library of Congress, public domain)

Declaration addressed to ‘opinion of Mankind’

It is fitting, then, that the Declaration is not addressed to the Crown, but rather to the broader “opinion of Mankind” as the United States seeks entrance into the community of nations. Jefferson recasts the British Empire as a confederation of peoples and describes the colonialists as a people breaking their alliance with other people, thereby dissolving that confederation without committing an act of civil war.

The Declaration does not attack the way in which George III ruled Britain, advocate the overthrow of the British regime outside the American Colonies, or call for the other peoples of the British Empire similarly to rise up.

The philosophy of equality and rights that the Declaration of Independence announces in its second paragraph locates the specific indictments against the Crown into a broader framework of contractual government similar to that of the charters that the British king had issued to the colonies.

By 1776, concepts, derived from British Whigs like John Locke and Algernon Sydney, had become common in the Colonies who thought they were equally entitled to such rights as were Englishmen. Ironically, a majority of the 56 men, including Thomas Jefferson, who signed the Declaration owned slaves, whom they hardly treated, or intended to treat, equally.

Declaration of Independence as a rallying point

Historians now believe that the Declaration of Independence was read outside Independence Hall the day it was adopted. Word subsequently spread throughout the colonies through numerous newspapers and through copies of the Declaration that were distributed throughout the states and read to Patriot troops. The Document helped rally the colonies behind a common cause and was often greeted by celebrations similar to those that now mark Independence Day.

The Declaration also signaled foreign countries that the colonies did not plan on turning back and reconciling with the mother country. The governments of such countries could accordingly under international law intervene on behalf of a one nation (the United States) against another (Great Britain) rather than meddling in a civil war.

The signing of the Declaration of Independence, common for legal documents, did not actually take place until August 2 and thereafter, and the names of the signers were not subsequently printed until January of 1777.

Declaration was unclear about relationship between states

The final section of the Declaration that incorporates the language of Richard Henry Lee's resolution, formally declaring the independence of the United States does not define the nature of the relationship that these “united states” have with one another.

The text is unclear as to whether they are united only in their grievances and their act of independence, or whether a more permanent political or legal form of union exists.

Although the Declaration of Independence is often confused with the Constitution it did not establish a new government or even outline what that government would be, other than it should be established by “the consent of the government” and should respect fundament rights such as those later embodied in the First Amendment.

The Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1781, and the U.S. Constitution, written in 1787, would create institutional structures and define the relationship among the states with greater clarity. The first created a confederal government, where states dominated, and the second created a federal government, with a stronger national government that shared power with the states. However, it took the Civil War (1861-1865) to deny the right of states to secede unilaterally and the adoption of constitutional amendments to eliminate slavery and extend rights to former slaves.

Abraham Lincoln was among the prominent 19th century statesmen who saw in the Declaration’s universalistic aspiration a blueprint for a new and more egalitarian political community that included African Americans. Drawing from the language of the Declaration of Independence, his famed Gettysburg Address described America as “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

In the Declaration of Sentiments, delegates to the Seneca Falls Convention in New York in 1848, reformulated the words of the Declaration to declare that “all men and women are created equal.” Such an assertion meant that women were as equally entitled as men to assemble, speak, publish, and exercise other First Amendment freedoms.

Independence Day

Although John Adams had predicted that the new nation would celebrate July 2 as Independence Day, this honor went not to the day that Congress declared independence but to the day on which it explained its action through adopting the Declaration.

Early commemorations were often celebrated by speeches expounding on the wisdom of the Founding Fathers and the nation’s core principles. July 4th grew in symbolic importance when both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on July 4, 1826 — 50 years to the day after Congress adopted the Declaration. In 1852, Frederick Douglass used an Independence Day celebration to point to the nation’s failure to extend equality to African Americans.

In 1876 and in 1976, the nation participated in a wide variety of events commemorating the Declaration of Independence as it respectively celebrated its centennial and bicentennial. Plans have been made to have similar celebrations in 2026, which will mark the semi-quincentennial (250th anniversary) of the document

At a time often marked by national political division, the Declaration remains a powerful testament to the value of freedom of speech and press and the power of rhetoric in articulating timeless principles and uniting Americans around universal values.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2024 by John R. Vile, a professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University. Douglas C. Dow is a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas specializing in political theory, public law, legal theory and history, and American politics.