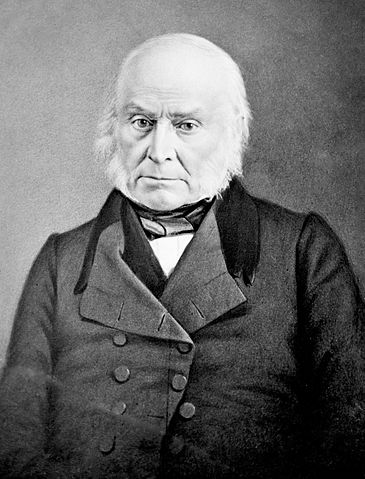

John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) was the sixth president of the United States, a legislator and an attorney.

Born in Braintree, Massachusetts, in 1767, he entered public service in his youth as a secretary to his father, John Adams, during the elder Adams’s work as an ambassador in Europe during the founding era.

John Quincy later served as a diplomat in several European countries, beginning with his appointment as minister to the Netherlands at the age of 26.

He was elected to the Senate in 1802 and later served as one of the greatest secretaries of state (in the administration of James Monroe), having been primarily responsible for the development of the Monroe Doctrine, warning against European military intervention in the Americas.

After disputed election, House selected Adams

Adams was the first son of a president of the United States to also become a president. The House of Representatives selected Adams in the disputed election of 1824, despite his challenger, Andrew Jackson, having won a plurality of the popular vote and the electoral college. During the proceedings in the House, Henry Clay of Kentucky, who was one of the four candidates in the race, threw his support behind Adams and was later appointed secretary of state by Adams.

Jackson and his supporters contended that the election of Adams had been achieved by a “corrupt bargain” and went on to campaign vigorously for his defeat in 1828. The electoral dispute split the Republican Party — the only party following the demise of the Federalist Party of John Adams after the end of the War of 1812 — with the National Republicans, or “Whigs,” supporting Adams and the Democratic Party supporting Jackson.

Adams, like his father, favored a strong national government and had no constitutional compunctions against federal appropriations for roads and other internal improvements. He strongly condemned John Tyler’s vetoes of such laws. Adams thought it was more important to be virtuous than to be popular and often had difficulty working with Congress or brokering compromises.

After Jackson defeated Adams in 1828, Adams retired to Massachusetts. In 1830 the Plymouth district elected him to the House of Representatives, where he served until his death, in 1848. As a representative, Adams was an eloquent leader in defense of civil liberties in general, and particularly the right to petition government.

In 1836, Southern members of the House managed to pass a “gag rule” to table all petitions on the subject of slavery. John Quincy Adams objected strenuously to any restriction on the right of any person to petition, which he identified as a right that “belongs to humanity” and which in no way depended upon the condition of the petitioner. Adams eventually won the repeal of the rule in 1844. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

Adams objected to gag rule against slavery in Congress

In the 1830s, abolitionists adopted a strategy of repeatedly petitioning the House of Representatives for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia and throughout the nation. In 1836, Southern members of the House managed to pass a “gag rule” to table all petitions on the subject of slavery. Adams objected strenuously to any restriction on the right of any person to petition, which he identified as a right that “belongs to humanity” and which in no way depended upon the condition of the petitioner. Adams eventually won the repeal of the rule in 1844.

Adams' defense of civil liberties led to his alliance to the abolitionist cause even though he was not an abolitionist himself. He is now also remembered for his oral argument before the Supreme Court in the case of the Amistad, in which he defended the freedom of a group of illegally purchased slaves who had seized control of their ship before arriving in Long Island, where they resisted extradition to Cuba.

Adams was one of the most biblically literate of all U.S. presidents. He served for a time as the vice president of the American Bible Society and authored a series of letters, later collected as a book, to his son on the importance of that book. Although he does not appear to have embraced orthodox Christianity, his home state did not disestablish the congregational church until 1833, and Adams, who had a strong sense of national destiny, has been linked to creating “a Puritan founding myth for the nation at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century” and of “making state-sponsored Christianization a hallmark of his presidency” (Smith 2022).

However, as a congressman, Adams opposed laws that would have mandated Sunday as a day of rest. As president, he did not declare national days of prayer and/or thanksgiving, and he disfavored alcoholic prohibition laws (Smith 2015, p. 95, 96, 105) believing this was a matter of individual self-control.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2024 by John R. Vile, dean of the Honors College and Middle Tennessee State University and a history professor. Paul J. Cornish is Associate Professor of Political Science at Grand Valley State University. He has published articles on the political thought of John Adams, and on the concepts of natural rights, toleration, and constitutional government in the Catholic natural law tradition