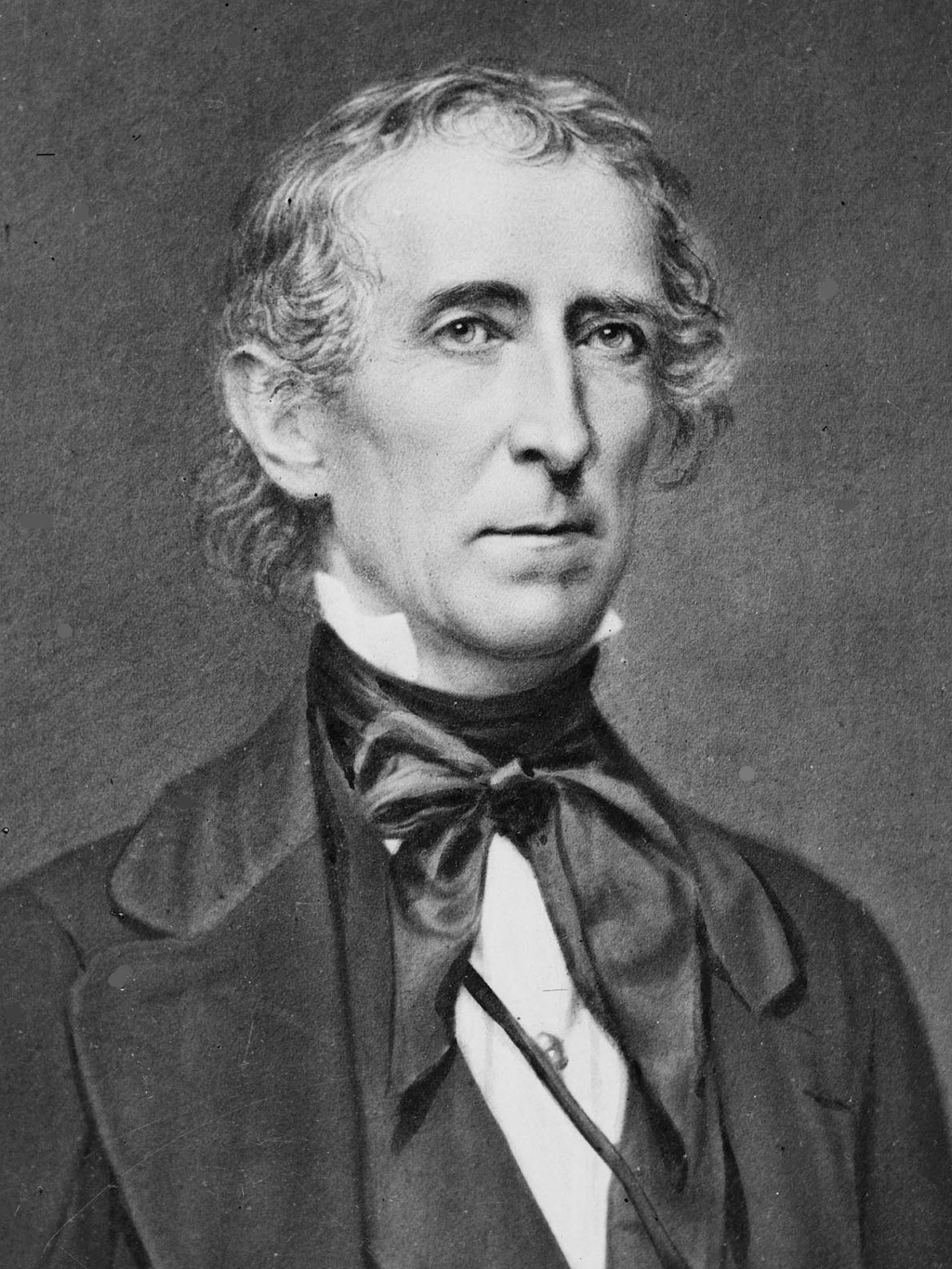

John Tyler (1790-1862) was born and raised in Virginia, where he attended the College of William and Mary and read law. He was elected at an early age to the state’s House of Delegates. During the War of 1812, he organized a militia company to defend Richmond.

He served successively as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, as governor of Virginia, as a U.S. senator and as vice president to William Henry Harrison. Harrison’s early death in office elevated Tyler to the presidency (the first individual to attain the job in this fashion) where he served from 1841 to 1845 as the nation's 10th president.

A former Democrat who had been used to balance the presidential ticket, Tyler is best known for his strong assertion that he would fill out Harrison’s term with full presidential powers and not as a mere “acting president” until a new election could be called. He had a far more vigorous conception of executive power than his fellow Whigs (who had formed largely in opposition to the powers exercised by President Andrew Jackson). He believed that congressional powers were more limited than most of his fellow Whigs, vetoed more bills (including a bank bill and many of the elements of Henry Clay’s American System) than any of his predecessors other than Jackson, and was even the target of an unsuccessful impeachment effort.

In his address of April 9, 1841, upon assuming the presidency, Tyler noted, with specific reference to members of his administration, most of whom would soon resign, that “Freedom of opinion will be tolerated, the full enjoyment of the right of suffrage will be maintained as the birthright of every American citizen.”

First Amendment issues

Tyler defended separation of church and state

In Tyler’s Fourth Annual Message of Dec. 3, 1844, he observed:

“A sacred observance of the guaranties of the Constitution will preserve union on a foundation which can not be shaken, while personal liberty is placed beyond hazard or jeopardy. The guaranty of religious freedom, of the freedom of the press, of the liberty of speech, of the trial by jury, or the habeas corpus, and of the domestic institutions of each of the States, leaving the private citizen in the full exercise of the high and ennobling attributes of his nature and to each State the privilege (which can only be judiciously exerted by itself) of consulting the means best calculated to advance its own happiness — there are the great and important guaranties of the Constitution which the lovers of liberty must cherish and the advocates of union must ever cultivate.”

As a one-time Democratic Republican, Tyler appears to have imbibed Jeffersonian notions of church-state relations. On July 10, 1843, Tyler responded to a letter from Joseph Simpson, a prominent Jew from Baltimore, Maryland, who had written to protest General Winfield Scott’s decision to preside over a missionary conference, apparently to be attended by other army officers.

Tyler responded that he assumed that the meeting was “nothing more than a contemplated assemblage of certain officers of the army and navy in their character of citizens and Christians, having for its object the inculcation upon others of their religious tenets, for, as they believe, the benefit and advantage of Mankind.” Tyler observed that “a similar call on the part of any other religious sect would be alike tolerated under our institutions,” and that if Scott attended, “it will not and cannot be in his character of General in Chief of the army.”

While acknowledging Scott’s right to the free exercise of his religious views, Tyler offered a defense of separation of church and state that accommodated non-Christian religions. Noting that the U.S. had “adventured upon a great and noble experiment . . . of total separation of Church and State,” he observed that “No religious establishment by law exists among us. The conscience is left free from all restraint and each is permitted to worship his Maker after his own judgment. The offices of Government are open alike to all. No tithes are levied to support an established Hierarchy, nor is the fallible judgment of man set up as the sure and infallible creed of faith.” He noted that religious freedom included “the Mohammedan and “the Hebrew.” Further observing that “The body may be oppressed and manacled and yet survived; but if the mind of man be fettered, its energies and faculties perish, and what remains is of the earth, earthly. Mind should be free as the light or as the air.” (Correspondence, 1904, 1-2).

Tyler served at time in which Bill of Rights did not restrict states

In 1833, the U.S. Supreme Court had decided in Barron v. Baltimore that the provisions of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, did not apply to the states.

However, during Tyler's presidency, Justice Joseph Story authored an opinion regarding religious freedom in Vidal v. Girard’s Executors (1844) stating that Pennsylvania common law did not void a bequest to a school that excluded ministers from teaching because this restriction was not intended to restrict all religious instruction at the school. While riding circuit in Massachusetts, Justice Joseph Story also decided in Folsom v. Marsh (1841) that the publication of a book on George Washington by the Rev. Charles W. Upham that contained letters from other works did not constitute “fair use” and thus violated copyright laws.

There was continuing debate during the Tyler administration about the constitutionality of the gag rule in Congress, which prohibited debate of anti-slavery petitions. John Quincy Adams finally won the fight to repeal this order in 1844.

Although there were two Supreme Court vacancies during Tyler’s administration, and he advanced five candidates, the only one to be confirmed was Samuel Nelson of New York, who served from 1845 to 1872.

Although Tyler was an active participant in a Peace Convention designed to avert the Civil War, he supported the Confederate states. He was elected to the Confederate Congress but died before being able to serve. He was buried with a Confederate flag draped over his coffin in a ceremony that the U.S. Congress did not officially recognize.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 12, 2023.