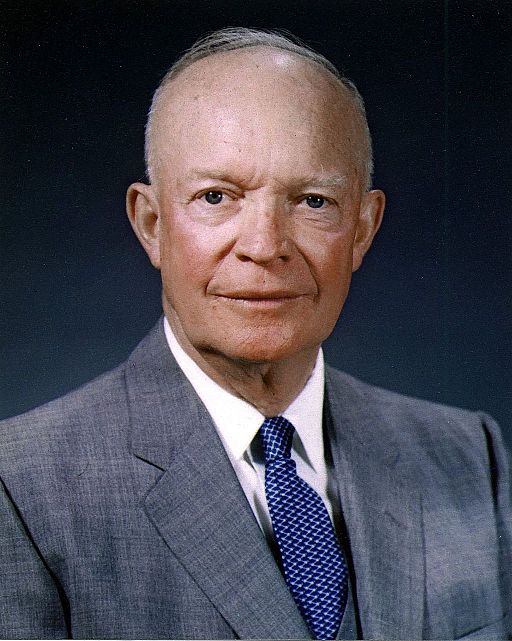

Dwight David Eisenhower (1890-1969) was born in Texas, raised in Kansas, and educated at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He served most of his life in the military and, as Supreme Allied Commander, supervised the invasion of France at D-Day during World War II.

After a stint as chief of staff of the U.S. Army and as president of Columbia University and after attempts by both political parties to recruit him, he won the 1952 Republican nomination for president. He served as president from 1953 to 1962, twice defeating Democrat Adlai Stevenson. Richard M. Nixon was his running mate.

Eisenhower ran for office in opposition to “Communism, Korea, and Corruption” and was able to bring the Korean War to a stalemate. Strongly anti-communist, Eisenhower was also a moderate who resisted large federal expenditures. He preferred to use the threat of nuclear war as a deterrent rather than engaging ground troops in foreign wars. In his famed farewell address, he warned of the perils of the “military-industrial complex.” The nation's 34th president, Eisenhower has been credited with exercising a “hidden hand” presidency in which his actions behind the scenes were almost as important as his public statements.

Eisenhower worked to diminish the influence of Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin whose investigations of alleged communists often threatened civil rights and liberties.

Eisenhower sought unity through civil religion

Eisenhower attempted to use civil religion as a way of uniting Americans in opposition to international communism, which was based on atheism. At his inauguration, Eisenhower asked the audience to join him in a prayer that he had composed for the occasion before giving his inaugural address.

In a frequently quoted speech to the Freedoms Foundation at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York on Dec. 22, 1952, Eisenhower noted that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” (Henry 1981).

In 1953, President Eisenhower presided over the first official prayer event, which is now known as the National Prayer Breakfast.

In 1954, during Eisenhower’s presidency, Congress added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance to the U.S. Flag, and. In 1956, it adopted the phrase “In God We Trust” as the American motto. Though opponents argue that the phrase “In God We Trust” amounts to a governmental endorsement of religion and thus violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment, federal courts have consistently upheld the constitutionality of the national motto.

Domestic Policies

Federal troops sent to support public school desegregation

Many Republicans had opposed the New Deal begun under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and sought to have it rolled back. But Eisenhower concentrated on streamlining rather than abolishing existing programs and continued the policy of attempting to contain international communism abroad.

Prior to his presidency, the Supreme Court had decided that the provisions of the First Amendment not only limited the national government but also limited the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, which had been ratified in 1868. Partly as a result of his appointment, the Supreme Court began incorporating other provisions of the Bill of Rights during his presidency and the two that followed.

As Black soldiers returned from World War II and Korea, they became increasingly insistent on securing rights at home for which they had fought abroad. This movement was accelerated in 1954 when the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education decided that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Although Eisenhower would have preferred that this process occur more gradually, he supported this decision and sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957 to enforce this desegregation decision, which Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus had opposed. The Supreme Court vindicated Eisenhower, and its own authority to order desegregation, in Cooper v. Aaron (1958).

First Amendment Issues

Court: First Amendment protects rights of association in NAACP case

Although Brown did not directly deal with the First Amendment, in NAACP v. Alabama (1958), the Supreme Court interpreted the First Amendment to protect the rights of association of members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People against state-induced disclosure of their names, which might subject them to retaliation.

Prosecution of communists leads to free speech rulings

Concern over international communism continued to influence domestic policies. In Dennis v. United States (1951), the Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of the Smith Act, which provided penalties for leaders of the Communist Party in the United States.

In Yates v. United States (1957), the high court narrowed that decision by distinguishing the mere belief in the eventual overthrow of capitalism from actual conduct meant to bring about that result.

In Watkins v. United States (1957), the Supreme Court, citing the First Amendment, overturned the conviction of a labor organizer who had refused to answer questions posed to him by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In Barenblatt v. United States (1959), however, the high court ruled that the interests in national security provided sufficient warrant for requiring a witness to testify in that case.

In overturning the prosecution of a motion picture for being sacrilegious, the Supreme Court in Burstyn v. Wilson (1952) extended constitutional protection to this medium. By contrast, in Roth v. United States (1957), the court held that pornography was not protected by the First Amendment and laid down a standard involving contemporary standards that, with some modifications, remains in force today.

Eisenhower appoints Warren, Harlan, Brennan to Supreme Court

Eisenhower had a major influence on the U.S. Supreme Court, with less attention to ideology than most of his successors (Eisenhower and Grosvenor 2020). His first appointment of former California Governor Earl Warren to replace Chief Justice Fred Vinson who had died in office was arguably his most consequential. Although Eisenhower perceived Warren to be a moderate, the Warren Court would gain a reputation as a liberal body which accelerated the application of provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states via the First Amendment.

Eisenhower’s appointment of John Marshall Harlan II, a U.S. Circuit Judge, to replace Justice Robert Jackson, arguably resulted in a justice who was more closely aligned with Eisenhower’s own moderate ideology.

Eisenhower’s decision to appoint a Democrat William Brennan to replace Sherman Minton on the Court tilted the court in a more liberal direction, whereas his nominations of Charles Whittaker to replace Stanley Reed and Potter Stewart to replace Harold Burton were more moderate.

Although John F. Kennedy defeated Eisenhower’s vice president Richard Nixon in the 1960 election, Nixon would later serve as president from 1969-1974.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Jan. 14, 2024.