In Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952), the Supreme Court ruled that a New York education law allowing a film to be banned on the basis of its being sacrilegious violated the First Amendment.

New York Board of Regents did not allow ‘sacrilegious’ film to be shown

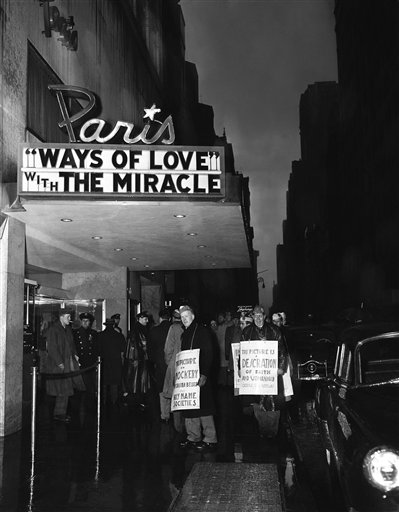

In The Miracle, a highly controversial Italian film, a peasant girl is seduced by a stranger she imagines to be St. Joseph and then gives birth to a son she believes to be the Christ child.

The New York Board of Regents rescinded the license to show the film, finding it “sacrilegious.” Joseph Burstyn, the film’s distributor, challenged the ruling. The New York Appellate Division upheld the decision, and the New York Court of Appeals affirmed. The Supreme Court unanimously reversed.

Court said constitutional landscape had changed since last film case

Justice Tom C. Clark’s opinion for the Court was the first concerning film censorship since Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (1915), which held that motion pictures were not protected expression, but merely theatrical business products.

Clark observed that the constitutional landscape had changed since 1915. In particular, the decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925) had made the First Amendment’s speech and press guarantees applicable to states by means of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause.

He also observed that motion pictures were increasingly used to reflect and influence public opinion and had thus changed so substantially that they could no longer be bound by Mutual Film.

Court said motion pictures had First Amendment protection

Clark rejected the arguments supporting censorship of movies: that movies entertained as well as informed, that they were a large-scale business conducted for private profit, and that they possessed a great capacity for evil.

Rather, motion pictures, Clark held, were a significant medium for the communication of ideas protected by the First Amendment.

Court struck down New York law requiring government permission to show films

Clark then examined the film-licensing scheme of New York that required government permission to show motion pictures. The Court in Near v. Minnesota (1931) had held prior restraint permissible only in exceptional circumstances and asserted that government bore a heavy burden in demonstrating the need for it.

Clark concluded that New York had not met this burden. Granting a government censor unlimited control over motion pictures and permitting the censor to suppress real or imagined attacks upon a religious doctrine was not, Clark argued, a legitimate interest of government.

Frankfurter said term ‘sacrilegious’ was too vague

In a lengthy concurring opinion, Justice Felix Frankfurter focused on the term sacrilegious.

As a consequence of his analysis, he determined sacrilegious to be an unconstitutionally vague statutory term, pointing to a violation of due process because it neither provides notice of illegal behavior nor provides the courts with a standard to judge administrative action.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. William C. Green (1954-2020) was a professor of political science and government at Morehead State University.