Although the First Amendment prohibits an established church, Americans are relatively religious, and many continue to identify the nation not only as the source of their religious freedoms, but also as the embodiment of their deepest religious aspirations.

Scholars often classify this identity between ideas of nationalism and religion under the concept of civil religion.

The term religion derives from two Latin verbs: religare, meaning “to bind,” and religere, which, like the Greek verb, alegein, means “to care for, to be concerned about.”

Civil religion is ethos of a society that undergirds a common good

By extension, religion can be defined as the “careful observance of a binding divine rule.” Civil religion is the bond that unites a people under the same laws and rules and provides a sense of inclusion, belonging, identity, unity and structure, worth, confidence, transcendence, and purpose. It is the ethos of a given society that sometimes enables citizens to sacrifice their lives for the common good.

The nature of civil religions can be best understood by considering the distinction between Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft, which roughly translate as “society” and “community.”

Gesellschaft is the “artificial,” heterogeneous, and competitive social milieu of modern urban society in which ties between individuals are loose, and personal interest, instrumental rationality, and the social contract are the glue that holds a society together.

Gemeinschaft is the “natural,” organic model of society prevailing in rural areas, which are typified by cultural homogeneity, cohesion, enforced harmony, common objectives, and emotional bonds.

Civil religions preserve “community”

As anticipated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract (1762), civil religions — with their quasi-religious rituals, liturgies, collective narratives, holidays, myths, heroes, symbols, and sacred places, as well as their empowering and galvanizing images, slogans, and principles — have become the cement of modern societies.

They function to preserve “community” alongside “society.” They effectively mobilize people around key issues and common concerns and goals, while conferring a religious significance, and thus conferring legitimacy on the dominant cultural practices, rules, value orientations, and institutions.

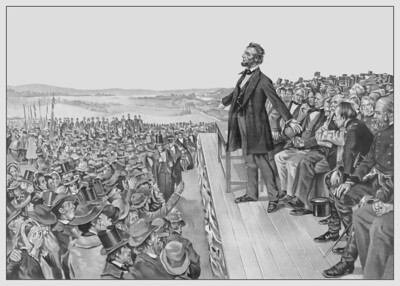

The distinctive features of the American civil religion include presidential monuments and libraries, war memorials, the display and veneration of “sacred scriptures” — among them the Constitution, Declaration of Independence, Mayflower Compact, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (pictured here) and his definition of the United States as “the last best hope of mankind.” (Image via Library of Congress, retouched image via Greg Goebel on Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Civic institutions as religions

Civic religions are alternative ways in which people can express their religiosity, and they generate that “collective effervescence” whereby a society venerates itself (Durkheim 1954).

The cult of secular institutions, which grows stronger when there is low demand for the available forms of religion and a rise of material welfare, sometimes varies from the orthodoxy of metaphysical religions; at other times it becomes exceedingly difficult to draw a boundary between civil religions and politicized faiths.

In the United States, “the Nation with the Soul of a Church” (Chesterton 1990), civil religion thrives on a comparatively high level of religiousness and takes various forms. It is a shaping ideology, future-oriented as well as past-oriented, which helps transform and integrate most of the immigrants who enter the United States.

American civil religion includes ‘sacred scriptures’ such as Declaration of Independence

The distinctive features of the American civil religion include presidential monuments and libraries, war memorials, the display and veneration of “sacred scriptures” — among them the Constitution, Declaration of Independence, Mayflower Compact, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and his definition of the United States as “the last best hope of mankind” — Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving Day, the White House, Ground Zero, the Pledge of Allegiance, the rhetorical invention of the “City upon the Hill” and of “Manifest Destiny,” and the motto “In God We Trust.”

People may be more or less aware of the existence of a civil religion, but under some circumstances, for example, on September 11, 2001, its presence is overwhelming, and such principles as gratuity, generosity, solidarity, and reciprocity intensify a drift toward a sort of ecstatic communal worship, calling for virtue and moral excellence and offering in return spiritual reassurance and fulfillment.

The establishment clause of the First Amendment stands as a firm obstacle in the path of an officially established national religion and against some governmental displays of religious symbols. Supreme Court decisions have thus prevented schools from forcing children to salute the American flag when this conflicts with their religious beliefs. In this photo, students in Miss O’Harra’s sixth grade class at P.S. 116 in New York City salute the American flag during the pledge of allegiance on Oct. 11, 1957. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Radical versions of civil religion

In extreme cases, civil religions may lead to the glorification and sacralization of nations and their political leaderships and the repudiation of the distinction between the public and the private spheres.

During the Depression and World War II, in Europe as well as in Japan, fascist and crypto-fascist governments held full powers, and states became moral entities. With the convergence of religious and political authority, the cult of sacralized collectivities supplanted the liberal democratic emphasis on individual rights.

The fascist civil religion blended pedagogic moralism, collective responsibility, social utility and regimentation, and technocratic and scientistic standards. It conferred an almost numinous quality and eschatological dimension — indeed, a vicarious sacredness — to the policy-making process and reinscribed emotional attachment, spiritual yearning, and an idealistic sense of citizenship in a society in which individuals were expected to put their own interests after the interests of society at large.

This radical version of civil religion promised an alternative, re-moralized modernity that would lead to a collective, mundane salvation and to the redemption of the national community from an alleged fallen state.

Fascists hoped for abolition of threats to “moral fiber” of society

Fascists shared an invidious condescension for real people and their shortcomings and were prepared to employ all possible means to shape and discipline them, including the abolition of pluralism and fundamental rights and the obliteration of all those forces and obstacles that they labeled a threat to the moral fiber of society.

National Socialists were particularly successful in injecting “magic,” “sublime,” and “epic” into a society awaiting its regeneration. Hitler observed that “those who see in National Socialism nothing more than a political movement know scarcely anything of it. It is even more than a religion: it is the will to create mankind anew” (Rauschning 1939: 242).

Do individuals exist for the state? Or the state for the individual?

Although the achievement of social cohesion and social justice may ultimately benefit greatly from a vibrant civil religion, citizens should remain vigilant to the risk that in times of dislocation and crisis, civil religion itself might justify the belief that individuals exist for the state and the community, and not vice versa.

Civil religion often portrays history as a perpetual battle between good and evil, urges believers to prove their faith and commitment, and underplays the question of the inherent worth of individuals.

Although the First Amendment prohibits an established church, Americans are relatively religious, and many continue to identify the nation not only as the source of their religious freedoms, but also as the embodiment of their deepest religious aspirations. In this photo, dozens of spectators wave American flags during a patriotic song sung by the Faithful Mens Singers of the Meridian, Idaho Assembly of God Church at the dedication of the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery in the foothills overlooking Boise, Idaho, Saturday morning, July 31, 2004. (AP Photo/Troy Maben, used with permission from the Associated Press)

First Amendment protects against forced national religion

Although the free exercise, free speech, and free press provisions of the First Amendment give individuals broad freedoms of religious expression, the establishment clause of that same amendment stands as a firm obstacle in the path of an officially established national religion and against some governmental displays of religious symbols.

Supreme Court decisions have thus prevented schools from forcing children to salute the American flag when this conflicts with their religious beliefs. In a similar vein, it has struck down postings of the Ten Commandments in public schools. The Court has generally been more tolerant of religious symbols displayed, as in the case of holidays, in conjunction with secular ones.

Professor Philip Gorski, a former student of Robert Bellah, recently wrote a book in which he argues for reinvigorating a type of civil religion that steers between what he describes as “religious nationalism,” which he associates with the idea that America is a Christian nation that can rarely do wrong, and what he calls “radical secularism,” which seeks to suppress all religious expression in the public square (2017, p. 4).

Gorski observes that: “The Civil religious tradition passes these tests because it is neither idolatrous nor illiberal, because it recognizes both the sacred and the secular sources of the American creed, because it provides a political vision that can be embraced by believers and nonbelievers alike, and because it is capacious enough to incorporate new generations of Americans” (p. 4).

This article was originally published in 2009. Stefano Fait was a graduate student in Trento, Italy.