The freedom of association — unlike the rights of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition — is a right not listed in the First Amendment but recognized by the courts as a fundamental right.

First Amendment protects two types of associative freedom

There are two types of freedom of association: the right to expressive association and the right to intimate association.

Additionally, the First Amendment protects a right to associate and a right not to associate together.

Expressive association refers to right to associate for expressive, often political purposes

The right to expressive association refers to the right of people to associate together for expressive purposes – often for political purposes. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized this right in NAACP v. Alabama (1958), reasoning that individual members of the civil rights group had a right to associate together free from undue state interference.

In that case, the state of Alabama sought to require the NAACP to disclose its membership list. In his majority opinion, Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote: “It is beyond debate that freedom to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas is an inseparable aspect of the ‘liberty’ assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech.”

This case and others caused leading First Amendment scholar Thomas I. Emerson to write that “freedom of association in the United States has assumed increasing significance as modern society has developed, and problems of associational rights have given rise to new and perplexing constitutional issues.” (35).

(See list of expressive association court cases.)

Kathy Ebert, former vice-president of the Minneapolis chapter of the Jaycees, addresses a 1984 press conference heralding the U.S. Supreme Court decision which says states may force the Jaycees to admit women as full members. Ebert is one of three women who filed the original brief with the Minnesota Human Rights department which finally reached the Supreme Court, who addressed the concept of intimate association. (AP Photo/Jim Mone, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Intimate association refers to right to maintain private associations without interference

The right to intimate association refers to the right of individuals to maintain close familial or other private associations free from state interference. Such rights include the right to marriage, the rearing of children, and the right to habitate with relatives.

Some courts place the right to intimate association under the Due Process Clause, but others place it under the ambit of the First Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court addressed the concept of intimate association in Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984), reasoning that the state of Minnesota’s interests in eradicating gender discrimination trumped the right of male members in social clubs to associate only with males and not females.

Freedom of association often conflicts with anti-discrimination law

A key aspect of freedom to associate is the ability of a group to associate with like-minded persons. Some freedom of association cases have proven difficult to navigate for the courts, because the freedom to associate or not associate often runs headlong into a state public accommodation or anti-discrimination law.

For example, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the associational rights of the Boy Scouts of America in excluding James Dale, an assistant scoutmaster, because he was gay. The Court ruled 5-4 in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000) that the state “interests embodied in New Jersey’s public accommodations law do not justify such a severe intrusion on the Boy Scouts’ rights to freedom of expressive association.”

(See list of anti-discrimination law court cases.)

Freedom of association concerns rights of political parties

Another line of freedom of association cases concern the rights of political parties to set their own rules and govern their internal affairs.

For example, the Court ruled in Tashjian v. Republican Party of Connecticut (1986) that the Republican Party of Connecticut could invite independent voters to vote in its primary.

Similarly, the Court in California Democratic Party v. Jones (2000) ruled that a state law mandating open primaries violated the associational rights of political parties. The law stated: ““[a]ll persons entitled to vote, including those not affiliated with any political party, shall have the right to vote … for any candidate regardless of the candidate’s political affiliation.”

The Court ruled that the First Amendment shielded the political parties in determining whether to open up their primaries to all voters of all parties.

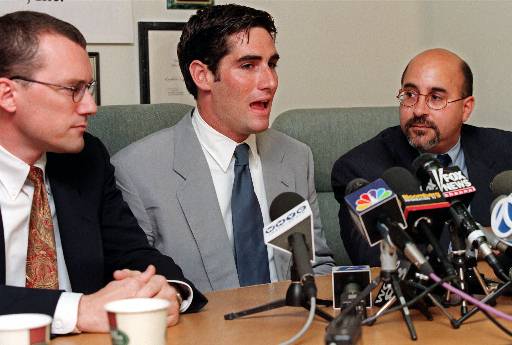

Some freedom of association cases have proven difficult to navigate for the courts, because the freedom to associate often runs headlong into a state anti-discrimination law. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the associational rights of the Boy Scouts of America in excluding James Dale, pictured here in 1999, because he was gay. The Court ruled that the state “interests embodied in New Jersey’s public accommodations law do not justify such a severe intrusion on the Boy Scouts’ rights to freedom of expressive association.” (AP Photo/Stuart Ramson, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Public employees, union issues fall under freedom of association

Still another line of freedom of association cases concerns the rights of public employees to belong to different social groups. In some instances, courts have ruled that a public employer can discipline or discharge a public employee for what it deems unsavory associations. For example, courts have determined that prison officials can discipline prison guards for belonging to a white supremacist group or to a motorcycle club with outlaw ties.

A related line of cases concerns employees’ associational rights regarding union dues. These cases have reached the U.S. Supreme Court. (See list of union regulation and right to work court cases.)

In Abood v. Detroit Board of Education (1977), the Supreme Court ruled that unions could not force employees to pay for fees for ideological and political activities not relevant to the union’s basic collective-bargaining duties. The Court ruled that requiring public employees to pay fees to support ideological causes they objected to violated their associational rights. The Court broadly upheld the concept of mandatory service fees.

However, in 2018 in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the Court overruled the allowance of mandatory service fees. In Janus, the Court said an Illinois law requiring non-union members to pay service fees to unions representing them in collective bargaining was an unconstitutional form of compelled speech.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.