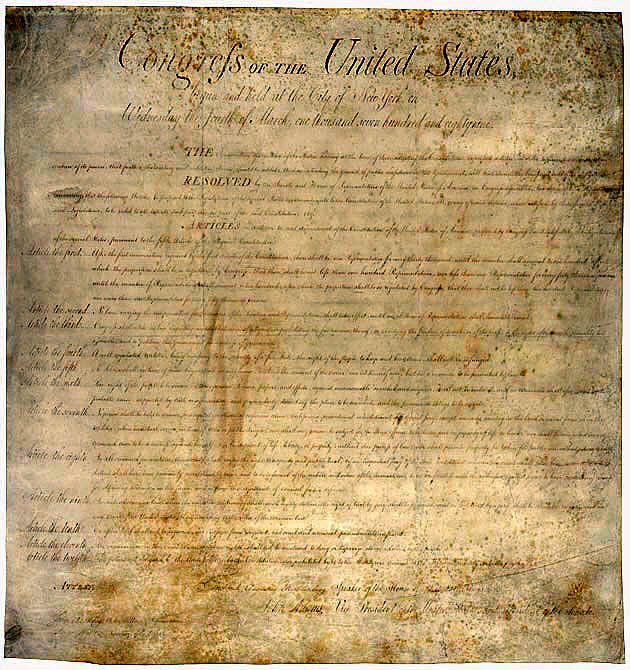

The Bill of Rights consists of the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

In response to the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which guided the fledging nation from 1781 to 1798, the country’s leaders convened a convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to amend the Articles, but delegates to the Convention thought such a step would be inadequate and took the more radical one of proposing a new document. From the Virginia and New Jersey Plans, a “Great (Connecticut) Compromise” was reached that resolved some of the factional disputes between the large and small states involving representation with Congress. The Convention also adopted scores of other compromises on slavery, on forming each of the three branches of the national government, on the relationship between this government and the states, and on other issues.

Article V of the new constitution provided that two-thirds of both houses of Congress (or a convention proposed by that number) could propose amendments. These would go into effect if and when they were ratified (at congressional specification) either by three quarters of the state legislatures or by conventions within the states.

Bill of Rights was added to Constitution to ensure ratification

When the Convention reported the Constitution to the state conventions for ratification, the nation split between Federalist supporters of the new document and Anti-Federalist opponents. Although many feared that the new federal government was too strong by comparison with its confederal predecessor, others were especially concerned that it did not, like most state counterparts, have a bill of rights (of the 11 state constitutions in place in the years after independence, 7 had bills of rights).

Although many Federalists initially opposed such a bill on the basis that it was unnecessary because the Constitution had not entrusted powers to violate such rights to the three branches, to ensure ratification of the document, key Federalists, including James Madison, agreed to support such a bill of rights once the Constitution was adopted. They were hoping in part to avoid the calls for a second constitutional convention, which might undo much of the work of the first. Federalists accordingly pushed for the use of the congressional proposal and state legislative ratification mechanism of constitutional change, and the Bill of Rights came into effect in December 1791, after ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures.

Federalists and Anti-Federalists argued over new Constitution

The level of support for the new Constitution varied. During the debate over its ratification, the Federalists grounded their support for the document in the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation. In late October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays appeared in print bearing the pen name Publius. These essays, which became known as the Federalist Papers, were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay. They presented a succinct series of arguments that, even today, are revered in the annals of political theory. The essays addressed the manner in which the new republican government, based on federalism and separation of powers, would guard against the tyranny of interest groups and other threats.

However, the Anti-Federalists were not convinced that these safeguards were adequate. Led by George Mason, Patrick Henry, and Elbridge Gerry, the Anti-Federalists wrote their own essays, basing their arguments on the tyranny of the British monarchy so resented by the 13 original colonies. AntiFederalists sought additional protections that would guard against an overly centralized and oppressive national government.

Ratification was a long process

Ratification of the U.S. Constitution was a slow and arduous process that was especially hard-fought in some of the more populous states including Massachusetts, Virginia and New York. Although the approval of only nine states was needed to ensure the document’s ratification (Article VII), ultimately the support of all 13 states was secured. Thus from the ashes of the Articles of Confederation emerged a federal system with enduring features such as republicanism (representative democracy), separated institutional powers, and a system of checks and balances. The Constitution set forth the institutional structures, players, processes, and procedures for governing the new nation through a series of seven articles.

Despite the seemingly apparent victory achieved in ratifying the Constitution, the founders failed to resolve the continuing debate over limiting the powers of the national government. As Alexander Hamilton remarked in Federalist No. 84, “the most considerable of the remaining objections is, that the plan of the convention contains no bill of rights.” To ease the process toward ratification, supporters such as Revolutionary War hero and first president George Washington supported creating a series of guarantees that would ultimately prevent the national government from tampering with certain rights and liberties deemed essential to a democratic form of government.

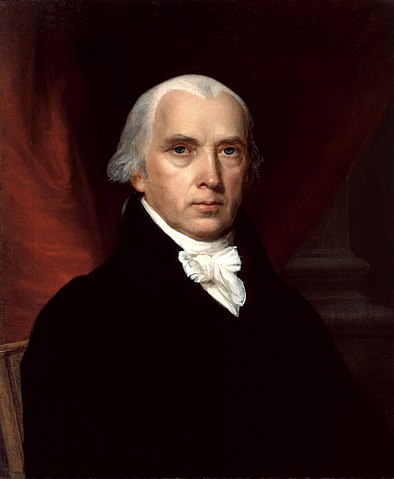

James Madison composed the Bill of Rights

James Madison, who appears to have been influenced on the subject in part by letters from Thomas Jefferson and in part by the hope of preserving the new document against changes to its essential structures, took the lead in the First Congress in composing and sponsoring the Bill of Rights.

Although the list of rights and liberties suggested by the former colonies was extensive, Madison narrowed it to nine amendments, with 42 different guarantees, largely drawn from state bills or declaration of rights like the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Congress in turn rearranged these into 12 proposed amendments. Ten of these amendments (all but one involving congressional representation, which was never adopted, and another relating to the timing of congressional pay raises which was much later ratified as the 27th Amendment) became part of the U.S. Constitution in 1791 after securing the approval of the required three-fourths of the states. (Read full text of the first 12 proposed amendments and then 10 amendments adopted as the Bill of Rights).

Madison, who thought that states and local governments were more likely to threaten civil liberties than the national government, was unable to secure the adoption of an amendment that would also have prevented states from interfering with rights of conscience or freedom of the press.

The Bill of Rights supplemented the structural mechanisms within the Constitution as well as the specific restraints on Congress (found in Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution) and on the states (found in Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution) by preventing addition federal abuses of individual liberties.

James Madison, who appears to have been influenced on the subject by Thomas Jefferson, took the lead in the First Congress in composing the Bill of Rights. Although the list of rights and liberties suggested by the former colonies was extensive, Madison narrowed it to nine amendments with 42 separate rights, which in turn were rearranged into 12 amendments that Congress proposed. Ten of these became part of the U.S. Constitution in 1791 after securing the approval of the required three-fourths of the states. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, painted by John Vanderlyn 1816, public domain)

The First Amendment guarantees religious freedom

The First Amendment, one of the more symbolic and litigious of the amendments, guarantees fundamental rights including freedom of religion, speech, and the press, and the rights to assemble peacefully and to petition the government.

Two provisions of the First Amendment relate to religion. They prevent Congress from adopting any laws “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Adopted at a time when some states had established religions, which received state support, the prohibition against congressional legislation initially left these establishments in place, to be gradually eliminated by the sates themselves — Massachusetts, the last state to do so, did this in 1833.

The establishment clause has long been associated with the idea of separation of church and state and has, in more recent times, been used to prohibit state-sponsored devotional prayer, Bible reading, and related practices in public schools; to limit governmental aid to parochial schools; and, at times, to strike down state-sponsored religious displays.

For many years, the Supreme Court employed a three-part Lemon Test, named for the 1971 Supreme Court decision in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). It required that laws have a secular purpose, that their primary effect neither advance nor inhibit religion, and that they did not foster “excessive government entanglement with religion.” In recent years, the Supreme Court has largely abandoned this test, often paying great attention to historical practices and focusing primarily on whether laws discriminate against religious entities and/or whether practices have a coercive influence on participants, especially in classroom settings.

The free exercise clause in the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting religious beliefs and practices, although exceptions have been made in situations in which ceremonial practices threaten individual safety or welfare.

The First Amendment addresses freedom of expression

The First Amendment also addresses freedom of expression. The free expression clause guarantees the rights of individuals and the press to speak freely about issues, even those deemed controversial. Freedom of speech has generated substantial debate and legal controversy.

Generally, the Amendment forbids restrictions based on the content of speech, while recognizing valid time, place, and manner restrictions. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. developed the clear and present danger test means for deciding whether a particular speech directed against governmental actions is protected by the First Amendment. This test has subsequently been refined, particularly in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), to protect even provocative speech that does not present an imminent threat of violent lawless action.

Courts have ruled that neither “fighting words” nor "true threats" are protected by the First Amendment, because they inflict injury or incite violence. Miller v. California (1973) has permitted further restrictions on speech that is obscene under a three-part test.

Courts have, however, recognized fairly broad rights of symbolic speech, including burning the U.S. flag in protest. The right of students to wear black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam war was recognized in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969).

Similarly, the press is also protected by the doctrine of no prior restraint, which has developed out of the First Amendment and was articulated in Near v. Minnesota (1931). Under this doctrine, government restrictions and the licensing of media content prior to publication are unconstitutional even though publications deemed libelous might later be prosecuted. The case of New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) has, however, made it more difficult to win libel or defamation judgments for public figures than for private individuals.

Interpretations of the right to assemble have been further applied to include the right of association in organizations. Although the right to assemble includes peaceful protests, parades, and demonstrations, it does not extend to the right to prevent access to or to break into public buildings.

The Second Amendment

The Second Amendment provides that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” This amendment was considered important because in the Revolutionary War citizens had to protect themselves from tyranny and threats to their safety and that of the nation. In recent years, however, the Supreme Court has argued that the amendment was also designed to protect the right of individual self-defense. There is continuing controversy over the degree to which Congress can constitutionally regulate the access and lethality of weapons available to the general public or to groups like youth or the mentally ill, within it.

The Third Amendment

The Third Amendment also has its roots in the Revolutionary War era. It protects personal privacy by preventing the quartering of soldiers in a private home without the owner’s consent in peacetime, or according to the prescribed law in times of war.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment prevents “unreasonable searches and seizures,” and requires authorities to show probable cause to obtain warrants to search and seize dwellings and property. It was adopted in part out of reaction to the writs of assistance, which the British had used to raid private households and businesses. The Supreme Court has applied the amendment to electronic surveillance.

The Fifth Amendment

The Fifth Amendment also deals with personal rights and certain guarantees against the unconstitutional treatment of accused persons. It requires a grand jury indictment for serious crimes, prohibits repeated prosecution for the same offense (double jeopardy), and prevents the government from taking life, liberty, or property without due process of the law. The well-known saying “taking the Fifth” is derived from the provision that no persons shall be compelled in any criminal case to testify against themselves — that is, submit to self-incrimination. This amendment also addresses the concept of “eminent domain” — requiring that owners of private property seized for public use must receive just compensation for that property.

The Sixth Amendment

The Sixth Amendment sets forth additional guarantees for persons on trial: the right to be informed of an accusation, the right to have a speedy and public trial, the right to confront witnesses, and the right to legal counsel for defense. Since its historic decision in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the Supreme Court has held that the right to counsel includes the right to appointed counsel for individuals who cannot afford it. The court has also required arresting officers to inform individuals of this right and the right against self-incrimination.

The Seventh Amendment

The Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to a jury in civil cases in which the “value in controversy” exceeds $20.

The Eighth Amendment

Also related to trials, the Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bails and fines and “cruel and unusual punishment” for those found guilty of a crime. To date, the Supreme Court has ruled that the imposition of capital punishment for certain crimes, or by certain means, is illegal, but it has not ruled that the penalty is per se unconstitutional.

The Ninth and Tenth Amendments

The Ninth Amendment protects rights not specified in the Constitution, and the 10th Amendment reserves for the states or citizens all other powers not delegated to the national government or denied to the states. Because these amendments do not enumerate specific constitutional rights, some scholars are hesitate to include them under the designation of the Bill of Rights.

Despite their ratification as formal amendments to the U.S. Constitution, the amendments of the Bill of Rights were initially applied only to the powers of the federal government and not those of the states. That situation changed, however, after ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment on July 9, 1868, after the Civil War. It declared that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” and provided the basis for the argument that the rights in the first 10 amendments now applied to the states. (Image of stamp celebrating 175th anniversary of the Bill of Rights via National Postal Museum, public domain)

Bill of Rights initially only applied to the federal government but has been incorporated against the states

Despite their ratification as formal amendments to the U.S. Constitution, the amendments of the Bill of Rights initially applied only to the powers of the federal government and not those of the states — the First Amendment thus begins with the words “Congress [a branch of the federal government] shall make no law.”

This limited application was reaffirmed in the 1833 Supreme Court decision Barron v. Baltimore. As a consequence, the provisions in the Bill of Rights played a relatively small role in the first century of the nation’s existence.

That situation changed, however, after ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868, after the Civil War. It declared that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” and provided the basis for the argument that the rights in the first 10 amendments now applied to the states.

But even then, only selective incorporation, or the application of certain but not all portions of the Bill of Rights, occurred through a series of Supreme Court decisions. One of the most important of these was Gitlow v. New York (1925), incorporating freedom of speech. Subsequent cases have applied all of the guarantees of the First Amendment, and almost all of the other guarantees in the Bill of Rights, to the states.

In Carolene Products Footnote Four (1938), the Supreme Court, which had largely shifted away from protection for property rights, indicated that it would give particular solicitude to laws that conflicted with specific provisions within the Bill of Rights. The Suprme Court headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren was especially active in applying provisions relating the rights of criminal defendants in the Fourth through Eighth Amendments to the states.

Scholar Gerard N. Magliocca has demonstrated that, in part because the first 10 amendments did not follow the traditional form of previous bills or declarations of rights, which typically preceded rather than were appended to the end of constitutions, it was uncommon to characterize the first 10 amendments as the “bill of rights” until after the Spanish-American War in 1898. At that time, American leaders promised that these rights (or at least some of them) would protect residents in the new foreign colonies that the nation had acquired.

Bill of Rights calms fears about increasing federal power

Just as Federalists had used the Bill of Rights to assure state ratification of the Constitution in an earlier era, so too, modern American leaders subsequently used the protections to allay fears about increasing federal powers, such as those that Congress assumed during the New Deal, and to contrast American values with those of the totalitarian powers against which the nation was arrayed in World War II and the Cold War.

This list of guarantees has provided protections against the arbitrary and tyrannical treatment of citizens by their government, and has been understood to include a right to privacy and the right to travel. Many decisions by the Supreme Court have reinforced the protection of these liberties and further extended the application of the First Amendment and other provisions within the Bill of Rights to state and local governments.

This article was originally published in 2009 and was last updated in 2024 by John R. Vile, the dean of the Honors College and Middle Tennessee State University. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University.