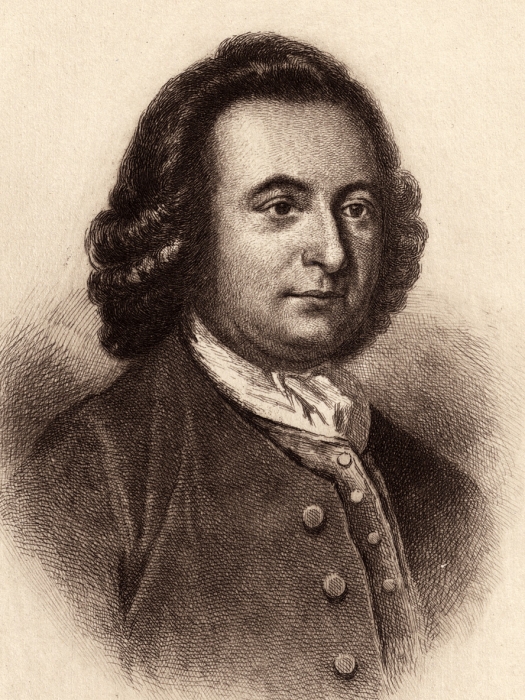

George Mason IV (1725–1792), a Virginia planter, statesman and one of the founders of the United States, is best known for his proposal of a bill of rights at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. As an Anti-Federalist, he believed that a strong national government without a bill of rights would undermine individual freedom. Mason also significantly contributed to other documents that advanced the development of the First Amendment.

Mason was born on a plantation in Fairfax County, Virginia. He was an early proponent of independence from Great Britain and worked throughout his life for the settlement of the western frontier, where he had invested in a land company. Mason was involved in early efforts in Virginia to boycott British goods in reaction to improper taxation and was elected to the legislature that was entrusted with writing the Virginia Constitution in 1776.

Mason drafted Virginia Declaration of Rights

Part of his responsibility involved drafting the Virginia Declaration of Rights. In part at the insistence of James Madison, the Virginia declaration came to include a strong guarantee of religious liberty (and not simply religious toleration as Mason had first proposed) that was similar to the free exercise clause later included in the First Amendment. It also contained a provision protecting freedom of the press, although it did not include a comparable protection for freedom of speech. Thomas Jefferson borrowed from and refined Mason’s assertion that “all men are born equally free and independent” when he wrote the Declaration of Independence.

Although not formally trained as a lawyer, Mason served for much of his life as a justice of the Fairfax County Court. However, he missed more sessions than most of his colleagues and often used his poor health and family circumstances (his first wife died leaving him with nine children) to turn down opportunities to serve in the state or national legislatures. Although initially appointed to a commission to rewrite the laws of Virginia, he resigned, leaving the majority of the work to Jefferson.

Mason attended Constitutional Convention

Mason did attend the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and was among the more effective delegates. He was suspicious of governments at all levels and was a consistent advocate of republicanism.

In the end, he was one of three remaining delegates who refused to sign the Constitution. One of several reasons that he offered in explanation was the absence of a bill of rights, for which he had helped to pave the way by consistently supporting a formal amending process. Curiously, Mason opposed the provision within the Constitution prohibiting ex post facto laws, and he seems to have conceived of the Bill of Rights more as a way of educating citizens than as a series of enforceable judicial restraints. Although he owned slaves, he also gave an impassioned speech against the “peculiar” institution.

Mason subsequently served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, and a neighboring county elected him as a delegate to Virginia’s ratifying convention.

He was sometimes overshadowed among the Anti-Federalists by Patrick Henry, but Mason played a constructive role in pointing to perceived flaws in the new document and in recommending subsequent amendments. Although his opposition to the Constitution largely ended his relationship with George Washington, Mason remained on good terms with Anti-Federalist James Monroe and with constitutional supporters Jefferson, Madison, and John Marshall. Despite initial concerns over the amendments that would be offered, Mason warmed to the Constitution after the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. He died at his Virginia estate, Gunston Hall, in 1792.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.