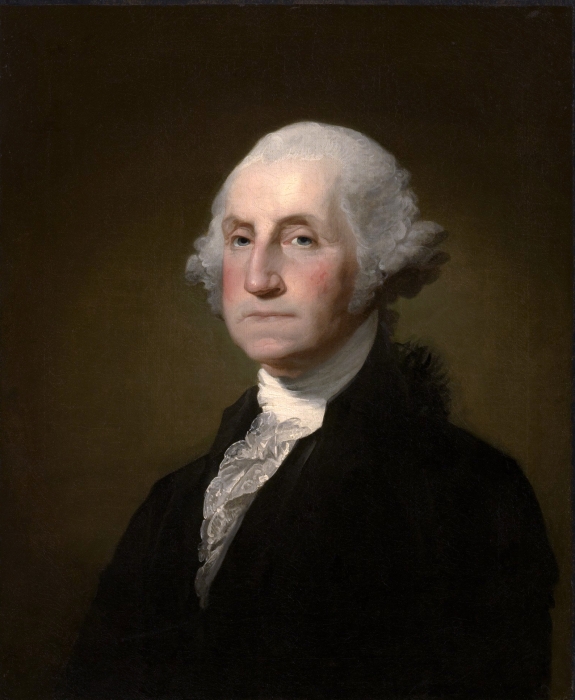

George Washington (1732–1799), Revolutionary War hero and first President of the United States, was born in Westmoreland County in the Tidewater region of Virginia.

Washington fought with British General Charles Cornwallis against the French and Indians and emerged from the First Continental Congress as the individual whom the colonists most trusted to lead them in their long, but ultimately successful, fight against the British during the Revolutionary War. Colonists often likened him to Cincinnatus, the Roman general who left his fields to fight on behalf of his country and then returned to his home.

Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention

Washington’s return to his home, Mount Vernon, was interrupted by yet another call from his country to attend the Constitutional Convention that met in Philadelphia in 1787. James Madison was especially influential in persuading Washington to attend. The attendees at the convention unanimously chose Washington as their president, and though he did not speak very often, his presence lent an air of gravity to the proceedings and his willingness to sign the Constitution was a major asset to Federalists who argued for the document’s ratification. He believed that the Constitution that emerged from the convention was the best possible for the time and praised the document for being amendable.

When a group of Presbyterians from New England communicated their concern in 1789 that the Constitution did not refer specifically to God or Jesus, Washington responded that:

The path of true piety is so plain as to require but little political direction. To this consideration we ought to ascribe the absence of any regulation, respecting religion, from the Magna Carta of our country. To the guidance of the ministers of the gospel this important object is, perhaps, more properly committed—it will be your care to instruct the ignorant, and to reclaim the devious—and, in the progress of morality and science, to which our government will give every furtherance, we may confidently expect the advancement of true religion, and the completion of our happiness (Kidd 2010, p. 216).

Washington favored Bill of Rights

Washington joined Madison and others opposed to delaying ratification until new amendments could be adopted, a decision that broke his long-time friendship with his neighbor George Mason. Nonetheless, in his Inaugural Address and in private correspondence, Washington indicated that he favored the adoption of a bill of rights to quiet public concerns.

Writing to Madison in 1789, he observed, “I see nothing exceptionable in the proposed amendments. Some of them, in my opinion, are importantly necessary, others, though in themselves (in my conception) not very essential, are necessary to quiet the fears of some respectable characters and well meaning Men. Upon the whole, therefore, not foreseeing any evil consequences that can result from their adoption, they have my wishes for a favourable reception in both houses” (Vile 1992, 50).

The Bill of Rights was introduced in the first Congress and subsequently adopted by the requisite number of states in 1791 during Washington’s first term to which he had been unanimously elected.

Washington’s Presidential terms set precedents

The Constitutional Convention appears to have designed the presidency with the expectation that Washington would be its first occupant. His two terms in office established many important precedents.

Contrary to his expectations, political parties (respectively led by Alexander Hamilton and by Madison and Thomas Jefferson) quickly disrupted the tranquility for which he had hoped, and his own pronouncements (rather than overt repressive legislation) about the development of democratic societies (which were predominately Democratic-Republican and pro-French) helped lead to the demise of those very societies.

Washington’s most important contribution to American political development may well have been his decision not to seek reelection after two terms, thus allowing for the transition to a new leader within his own lifetime.

Washington advocated for freedom of religion

Although Madison and Jefferson are more typically associated with advocacy of the rights in the First Amendment, Washington had a comparable commitment to civil liberties, especially religious freedom. His writings are remarkably free of religious prejudice. In a letter seeking workers for his estate in 1784, for example, he remarked, “If they are good workmen, they may be of Asia, Africa, or Europe. They may be Momometans, Jews or Christians of any Sect, or they may be Atheists” (Boller 1960, 487).

In 1775, he issued an order to Colonel Benedict Arnold, who was about to invade Canada. The order stated that Arnold’s army was “to avoid all Disrespect to or Contempt of the Religion of a Country by ridiculing any of its Ceremonies or affronting its ministers or Votaries” (Boller, 491); Washington later forbade his troops from celebrating Pope’s Day, wherein Protestants often burned effigies of the pope. He received acclaim from the Universalists when he supported the right of one of their clergy to serve as a chaplain in the Continental Army, and his respect also extended to Jews.

To that end, Washington responded to a letter written to him by a congregation in Rhode Island by observing, “All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection, should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving It on all occasions their effectual support” (Boller, 504).

Complete separation of church and state may not have been as much of a priority for Washington as it was for Madison. He appears to have initially supported Patrick Henry’s assessment for the support of religious teachers in Virginia, and as he emphasized in his Farewell Address, he believed that religion was a strong support for morality, which he thought was essential to good government.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.