The name Federalists was adopted both by the supporters of ratification of the U.S. Constitution and by members of one of the nation’s first two political parties.

Federalists battled for adoption of the Constitution

In the clash in 1788 over ratification of the Constitution by nine or more state conventions, Federalist supporters battled for a strong union and the adoption of the Constitution, and Anti-Federalists fought against the creation of a stronger national government and sought less drastic changes to the Articles of Confederation, the predecessor of the Constitution.

The Federalists included big property owners in the North, conservative small farmers and businessmen, wealthy merchants, clergymen, judges, lawyers, and professionals. They favored weaker state governments, a strong centralized government, the indirect election of government officials, longer term limits for officeholders, and representative, rather than direct, democracy.

Federalists published papers in New York City newspapers

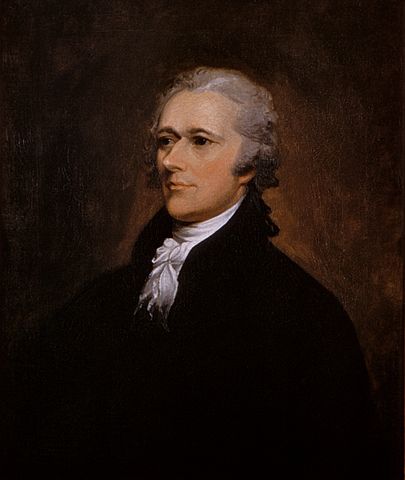

Faced with forceful Anti-Federalist opposition to a strong national government, the Federalists published a series of 85 articles in New York City newspapers in which they advocated ratification of the Constitution. A compilation of these articles written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay (under the pseudonym Publius), were published as The Federalist in 1788.

Through these papers and other writings, the Federalists successfully articulated their position in favor of adoption of the Constitution. Anti-Federalists wrote many essays of their own, but the Federalists were better organized; were (as their name suggested) advocating positive changes by proposing an alternative to the Articles of Confederation, which were generally considered to be inadequate; had strong support in the press of the day; and ultimately prevailed in state ratification debates. These papers remain a vital source for understanding key provisions within the Constitution and their underlying principles. The Federalist/Anti-Federalist debates further illustrate the vigor of the rights to freedom of speech and press in the United States, even before the Constitution and the Bill of Rights was adopted.

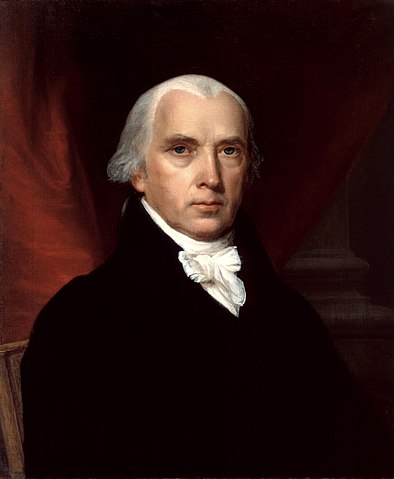

James Madison was another author of the Federalist Papers. To ensure adoption of the Constitution, the Federalists, such as James Madison, promised to add amendments specifically protecting individual liberties. These amendments, including the First Amendment, became the Bill of Rights. James Madison later became a Democratic-Republican and opposed many Federalist policies. (Image via the White House Historical Association, painted by John Vanderlyn in 1816, public domain)

Federalists argued separation of powers protected rights

In light of charges that the Constitution created a strong national government, they were able to argue that the separation of powers among the three branches of government protected the rights of the people. Because the three branches were equal, none could assume control over the other.

When challenged over the lack of individual liberties, the Federalists argued both that the Constitution already contained some such protections in Article I, Sections 9 and 10, that respectively limited Congress and the states; that the entire Constitution, with its institutional restraints and checks and balances was, in effect, a Bill of Rights; and that the Constitution did not include a bill of rights because the new Constitution did not vest the new government with the authority to suppress individual liberties.

The Federalists further argued that because it would be impossible to list all the rights afforded to Americans, it would be best to list none.

Prominent Anti-federalists like Patrick Henry, George Mason, and James Monroe and supporters of the new constitution like Thomas Jefferson, continued to argue that the people were entitled to more explicit declarations of their rights under the new government.

Federalists agree to add Bill of Rights

In the end, however, to ensure adoption of the Constitution, the Federalists promised to add amendments specifically protecting individual liberties. That is, Federalists such as James Madison ultimately agreed to support a bill of rights largely to head off the possibility of a second convention that might undo the work of the first.

Thus upon ratification of the Constitution and his election to the U.S. House of Representatives, Madison introduced proposals that were incorporated in 12 amendments by Congress in 1789. States ratified 10 of these amendments, now designated as the Bill of Rights, in 1791.

The first of these amendments contains guarantees of freedom of religion, speech, press, peaceable assembly, and petition and has also been interpreted to protect the right of association. Initially adopted to limit only the national government, these provisions have now been recognized as also limiting the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, which was adopted after the Civil War in 1868.

In 1798, during the administration of John Adams, the Federalists attempted to squelch dissent by adopting the Sedition Act, which restricted freedom of speech and the press. Although the Federalist Party was strong in New England and the Northeast, it was left without a strong leader after the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of Adams. Its increasingly aristocratic tendencies and its opposition to the War of 1812 helped to fuel its demise in 1816. (Image via the U.S. Navy, painted by Asher Brown Durand between 1735 and 1826, public domain)

Federalist Party supported Alexander Hamilton’s policies

Although the Bill of Rights enabled Federalists and Anti-Federalists to reach a compromise that led to the adoption of the Constitution, this harmony did not extend into the presidency of George Washington; political divisions within the cabinet of the newly created government emerged in 1792 over national fiscal policy, splitting those who previously supported the Constitution into rival groups, some of whom allied with former Anti-Federalists.

Those who supported Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s aggressive fiscal policies formed the Federalist Party, which supported a strong national government, an expansive interpretation of congressional powers under the Constitution through the elastic clause, and a more mercantile economy.

Their Democratic-Republican opponents, led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, tended to emphasize states’ rights and agrarianism.

In 1798, during the administration of John Adams, the Federalists attempted to squelch dissent by adopting the Sedition Act, which restricted freedom of speech and the press when directed against the government and its officials, but opposition to this law helped Democratic-Republicans gain victory in the elections of 1800. As the new president, Jefferson pardoned those who had been convicted under the Sedition Act.

Federalist Party ended in 1816

Although the Federalist Party was strong in New England and the Northeast, it was left without a strong leader after the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of John Adams. Its increasingly aristocratic tendencies and its opposition to the War of 1812 helped to fuel its demise in 1816.

This party was later succeeded by the Whig Party, which in turn was succeeded by the Republican Party. The Democratic-Republican Party was reformed by Andrew Jackson and became the modern Democrat Party.

This article was originally published in 2009 and was updated in February 2024 by John R. Vile, dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Mitzi Ramos is an Instructor of Political Science at Northeastern Illinois University.