Public school students enjoy First Amendment protection depending on the type of expression and their age. The Supreme Court clarified in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that public students do not “shed” their First Amendment rights “at the schoolhouse gate.”

Constitutional provisions safeguarding individual rights place limits on the government and its agents, but not on private institutions or individuals. Thus, to speak of the First Amendment rights of students is to speak of students in public elementary, secondary, and higher education institutions. Private schools are not government actors and thus there is no state action trigger.

Another important distinction that has emerged from Supreme Court decisions is the difference between students in public elementary and secondary schools and those in public colleges and universities. The latter group of students, presumably more mature, do not present the kind of disciplinary problems that educators encounter in grade school and high school, so the courts have deemed it reasonable to treat the two groups differently.

The court has protected K-12 students

The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). A group of Jehovah’s Witnesses challenged the state’s law requiring all public school students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Students who did not participate faced expulsion.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses argued that saluting the flag was incompatible with their religious beliefs barring the worship of idols or graven images and thus constituted a violation of their free exercise of religion and freedom of speech rights. The Supreme Court agreed, 6-3. Its decision overturned an earlier case, Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), in which the court had rejected a challenge by Jehovah’s Witnesses to a similar Pennsylvania law.

In Barnette, the court relied primarily on the free-speech clause rather than the free-exercise clause. Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote the court’s opinion, widely considered one of the most eloquent expressions by any American jurist on the importance of freedom of speech in the U.S. system of government. Treating the flag salute as a form of speech, Jackson argued that the government cannot compel citizens to express belief without violating the First Amendment. “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” Jackson concluded, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

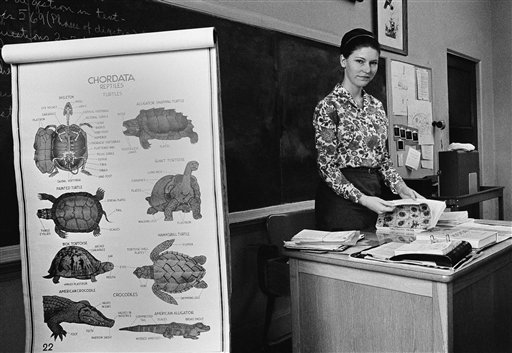

Biology teacher Susan Epperson, who challenged Arkansas’ ban on the teaching of the theory of evolution, is shown at her desk at Little Rock Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas in 1966. The Supreme Court in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) found an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools to be an unconstitutional violation of the First Amendment. (AP Photo)

In the early 1960s, the court in several cases — most notably Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) — overturned state laws mandating prayer or Bible reading in public schools. Later in that same decade, the Court in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) found an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools to be an unconstitutional violation of the establishment clause.

In Tinker, resulting in the court’s most important student speech decision, authorities had banned students from wearing black armbands after learning that some of them planned to do so as a means of protesting the deaths caused by the Vietnam War. Other symbols, including the Iron Cross, were allowed. In a 7-2 vote, the court found a violation of the First Amendment speech rights of students and teachers because school officials had failed to show that the student expression caused a substantial disruption of school activities or invaded the rights of others.

In later cases — Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) and Morse v. Frederick (2007) — the court rejected student claims by stressing the important role of public schools in inculcating values and promoting civic virtues. The court instead gave school officials considerable leeway to regulate with respect to curricular matters or where student expression takes place in a school-sponsored setting, such as a school newspaper (Kuhlmeier) or an assembly (Fraser). Years later, in Morse v. Frederick (2007), the Court created another exception to Tinker, ruling that public school officials can prohibit student speech that officials reasonably believe promotes illegal drug use. In L.M. v. Middleborough (2025), the Court declined to grant certiorari in a case that restricted student speech. Although the First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that school officials could suppress expression from a student wearing a t-shirt that read "There Are Only Two Genders," Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito both dissented from this denial of certiorari.

The different level of protection accorded to students in institutions of higher education is evident from several cases. Students on college and university campuses enjoy more academic freedom than secondary school students. In this photo, Karilyn Barker, editor of the campus newspaper at the Berkeley campus of the University of California, is seated, with editorial page editor Susan Werbe at Berkeley, California, 1968. (AP Photo/Robert W. Klein)

College students receive different levels of protection

The different level of speech protection for students in institutions of higher education, who are generally 18 years or older and thus legally adults, is evident from several cases. Students on college and university campuses enjoy more academic freedom than secondary school students.

In Healy v. James (1972), the court found a First Amendment violation when a Connecticut public college refused to recognize a radical student group as an official student organization, commenting that “[t]he college classroom with its surrounding environs is peculiarly the ‘marketplace of ideas.’”

In Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri (1973), a graduate journalism student was expelled for distributing on campus an “underground” newspaper containing material that the university considered “indecent.” The court relied on Healy for its conclusion that “the mere dissemination of ideas — no matter how offensive to good taste — on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’ ”

In this 2013 photo, Mary Beth Tinker shows one of her collection of armbands during an interview. Tinker was 13 years old in 1965 when she wore a black armband to school to protest the Vietnam War. School officials suspended her, leading to a lawsuit that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which said that school had violated the First Amendment rights of Tinker. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

However, in recent years, courts have applied principles and standards from K-12 cases to college and university students. For example, in Hosty v. Carter (7th Cir. 2005), the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that college officials did not violate the First Amendment and applied reasoning from the high school Hazelwood decision. More recent lower court decisions also have applied the Hazelwood standard in cases involving curricular disputes, professionalism concerns and even the online speech of college and university students.

Students in private universities — which are not subject to the requirements of the First Amendment — may rely on state laws to ensure certain basic freedoms. For example, many state cases have established that school policies, student handbooks and other relevant documents represent a contract between the college or university and the student. Schools that promise to respect and foster academic freedom, open expression and freedom of conscience on their campus must deliver the rights they promise.

Students and social media

More recently, courts have examined cases involving student speech on social media. In 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a school could not discipline a cheerleader who had posted on Snapchat a vulgar expression about not making the varsity squad. The court said in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. that the school’s regulatory interest was lessened in regulating the speech of students off-campus and on social media and that the cheerleader’s comment on Snapchat did not substantially disrupt school operations.

This article was originally published in 2009 and has been updated. Philip A. Dynia is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department of Loyola University New Orleans. He teaches constitutional law and judicial process as well as specialized courses on the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment.