In Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988), the Supreme Court held that schools may restrict what is published in student newspapers if the papers have not been established as public forums. The Court also decided that the schools may limit the First Amendment rights of students if the student speech is inconsistent with the schools’ basic educational mission.

Students sued high school for removing articles from school paper

Three high school student journalists, including Cathy Kuhlmeier, had sued their Missouri school district in 1983 for infringing on their First Amendment rights after the principal of Hazelwood East High School, Robert E. Reynolds, removed articles from a pending issue of Spectrum, the student newspaper. Two articles he objected to dealt with divorce and teen pregnancy.

Although the district court ruled against the students, they won their case in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the district appealed to the Supreme Court. In a 5-3 decision (there were only eight members of the Court, as the senate had not confirmed Justice Anthony M. Kennedy), the Supreme Court overturned the Court of Appeals’ ruling.

Supreme Court ruled in favor of the school

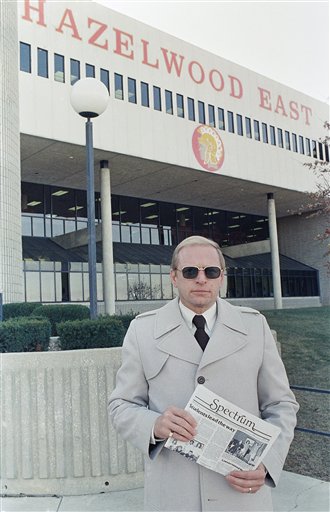

Robert Reynolds, principal of Hazlewood East High School, removed articles about teen pregnancy and divorce from the newspaper, setting off a case that went to the Supreme Court. ((AP Photo/James A. Finley)

Writing for the Court, Justice Byron R. White noted that First Amendment rights of students in the public schools “are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings.” Those rights, he argued, must be “applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment,” and schools do not need to tolerate student speech that is inconsistent with their “basic educational mission.”

In examining whether the Spectrum was a forum for public expression, White concluded that school facilities were public forums only if administrators had “by policy or practice” opened those facilities for “indiscriminate use by the general public.” The Court showed evidence that the paper had not “by policy or practice” been operating as a public forum.

Court said school control over newspapers did not violate student First Amendment rights

Hazelwood created a new standard for school-sponsored student speech as opposed to student-initiated speech. Educators, White said, do not violate student First Amendment rights “by exercising editorial control over the style and content of student speech in school-sponsored expressive activities so long as their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.” However, White also said students should go to court to protect their constitutional rights “when the decision to censor a school-sponsored publication, theatrical production, or other vehicle of student expression has no valid educational purpose.”

The Court also stated that a school acting as a publisher of a student newspaper or as a producer of a school play could disassociate itself from speech that would “substantially interfere with its work or impinge upon the rights of other students” and from speech that was “ungrammatical, poorly written, inadequately researched, biased or prejudiced, vulgar or profane, or unsuitable for immature audiences.” White argued that a school “must be able to take into account the emotional maturity of the intended audience” when determining whether content was appropriate for the readers.

Dissent: student expression must be accommodated to an extent

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote the dissenting opinion denying that the First Amendment permits “such blanket censorship authority.” He cited Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that said, “students in the public schools do not shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Public educators, Brennan said, “must accommodate some student expression, even if it offends them or offers views or values that contradict those the school wishes to inculcate.” Furthermore, Brennan said, “official censorship of student speech on the ground that it addresses potentially sensitive topics is . . . impermissible.”

Student censorship remains an issue

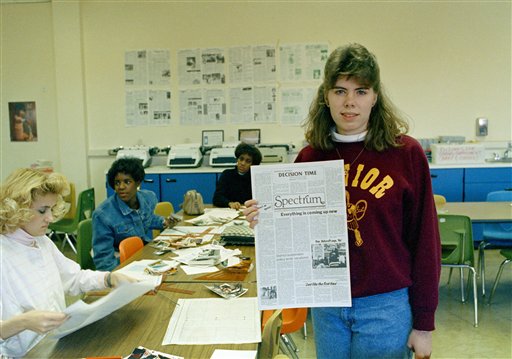

Leslie Smart, one of the three Hazelwood East High School journalism students that sued high school officials, reacts on Jan. 13, 1988 after learning that the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of the officials at the school. (AP Photo/James A. Finley)

Since the decision, the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) has held that student publications, which are operating as a public forum either “by policy or practice,” cannot be censored under Hazelwood. A public forum, the SPLC says, means that through policy or practice school officials have given student editors the authority to make content decisions. The SPLC also holds that school officials must show that they have a valid educational purpose for censorship and that the censorship is not intended to silence a specific viewpoint with which they disagree or a viewpoint that might be unpopular. School officials must prove that censorship has occurred because there would be “substantial disruption of school activities or an invasion of the rights of others.”

As of 2023, 17 states have enacted laws that protect the First Amendment rights of students. Scholars continue to debate the relationship between speech at the high school and college level. Student press advocates expressed great concern when a federal appeals court ruled in Hosty v. Carter (2005) that the Hazelwood framework applies at the university level.

This article was originally published in 2009. H. L. Hall was the Executive Director of the Tennessee High School Press Association.