In American jurisprudence, public school teachers, as public employees, do not forfeit all of their First Amendment rights to free expression when they accept employment. Both in pursuing and in imparting knowledge to others, public school teachers share some of the academic freedoms exercised by their college and university counterparts, albeit with limitations sometimes justified by the immaturity of their students. The courts have ruled on several cases involving teachers’ expressive rights.

Pickering established that teachers had First Amendment rights

In Pickering v. Board of Education (1968), the Supreme Court ruled that an Illinois high school science teacher, Marvin Pickering, had a First Amendment right to send a letter to the editor of the local newspaper. Pickering had been dismissed for sending a letter that criticized the school board for its allocations of funds for academics and athletics. In his majority opinion for the Court, Justice Thurgood Marshall agreed that Pickering’s First Amendment rights had been violated. He wrote that “the interest of the school administration in limiting teachers’ opportunities to contribute to public debate is not significantly greater than its interest in limiting a similar contribution by any member of the general public.”

A year after Pickering the Court reiterated that teachers possess First Amendment rights in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969). Although Tinker involved student speech, the Court wrote, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

In Givhan v. Western Line Consolidated School District (1979), the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the First Amendment claim of a public school teacher in Mississippi who had been discharged after complaining to her principal about racial discrimination. The Court explained that a public school teacher does not lose her free speech rights simply because she chose to speak on an issue of public concern to her employer directly rather than to the public at large.

Although Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) involved student speech, the Court wrote, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” In this 2013 photo, Mary Beth Tinker shows an old photograph of her with her brother John Tinker. When the school suspended the Tinkers for speaking out against the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to school, they took their free speech case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and won. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Hazelwood established that schools can regulate school-sponsored speech

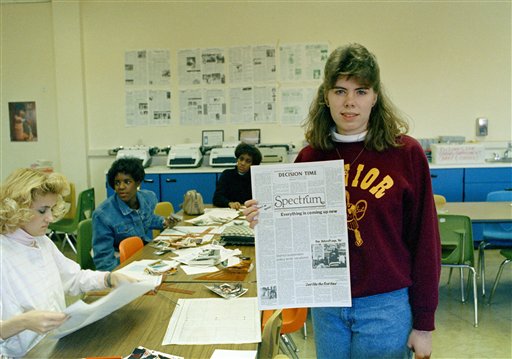

Other courts, when evaluating teachers’ First Amendment claims, have looked to another case involving student speech as a precedent. In Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court ruled that public school officials can regulate school-sponsored student speech as long as there is a legitimate educational purpose for their action.

Several lower courts have also applied Hazelwood to public school teachers for not appropriately monitoring their students’ classroom expression. In Lacks v. Ferguson Reorganized School District R-2 (8th Cir. 1998), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruled that a public school in Missouri could discharge an English teacher for failing to censor her students’ written works. Applying Hazelwood, the Eighth Circuit wrote, “A flat prohibition on profanity in the classroom is reasonably related to the legitimate pedagogical concern of promoting generally accepted social standards.”

In Miles v. Denver Public Schools (10th Cir. 1991), the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals applied Hazelwood to conclude that a public school teacher could be disciplined for talking about declining discipline and passing along a rumor about students having sex on a tennis court. “Because of the special characteristics of a classroom environment, in applying Hazelwood instead of Pickering we distinguish between teachers’ classroom expression and teachers’ expression in other situations that would not reasonably be perceived as school-sponsored,” the appeals court explained.

Although the principle of academic freedom usually holds in university settings, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in Bishop v. Aronov (11th Cir. 1991), also used the Hazelwood standard when evaluating the First Amendment claim of a university professor arising out of in-class instruction.

In this photo, Tammy Hawkins, editor of the Hazelwood East High School newspaper, Spectrum, holds a copy of the paper in 1988. The school was involved in a case that has been used to evaluate teachers’ First Amendment claims. In this case, the Court ruled that public school officials can regulate school-sponsored student speech as long as there is a legitimate educational purpose for their action. Several lower courts have also applied Hazelwood to public school teachers for not appropriately monitoring their students’ classroom expression. (AP Photo/James A. Finley, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Public employees no longer retain First Amendment protection for speech as part of their official duties

Teachers asserting a First Amendment violation must now clear an additional hurdle, as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006). In Garcetti the Court ruled that public employees do not retain First Amendment protection for speech as part of their official job duties.

The question remains whether Garcetti should apply in the academic setting, where academic freedom introduces another level of constitutional concern. The majority acknowledged this distinction in stating “there is some argument that expression related to academic scholarship or classroom instruction implicates additional constitutional interests that are not fully accounted for by this Court’s customary employee-speech jurisprudence.” Commentator Karen Daly notes that “Academic freedom is an ill-defined concept, especially when imported from the university campus to secondary and elementary schools.” Only time will tell which standard — the Pickering or the Hazelwood standard — will apply to the majority of public school teachers’ First Amendment claims and whether Garcetti will have an indelible effect.

Garcetti has been used to limit classroom speech

Several lower courts have applied the Garcetti ruling broadly to limit teacher classroom speech. For example, the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Brown v. Chicago Bd. of Educ. (7th Cir. 2016) that a public school teacher did not have a First Amendment claim when his principal disciplined him for using the N-word in a well-intentional lecture instructing students about not using racial slurs. Because of Garcetti, “Brown’s First Amendment claim fails right out of the gate,” the appeals court wrote.

Many teachers have fared poorly in First Amendment lawsuits after being disciplined for social media posts. Many courts show deference to school officials in disciplining teachers for speech deemed inappropriate or likely to cause problems at school.

The area of teacher free-speech rights is still evolving. Lower courts use a variety of standards from cases such as Pickering, Hazelwood, and Garcetti. Supreme Court review would provide much-needed guidance.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.