Public employees do not forfeit all their First Amendment rights when accepting government employment. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s late 19th-century mantra, spoken in McAuliffe v. Mayor of New Bedford (1892) when he was a justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, that a policeman “may have a constitutional right to talk politics, but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman,” no longer applies in First Amendment jurisprudence.

Today police officers and public employees can talk politics and retain their government jobs. Public employees have a right to speak out on matters of public concern or importance as long as the expression is not outweighed by the employer’s interest in an efficient, disruption-free workplace.

Court has said public employees do not lose their free speech rights

The Supreme Court recognizes that public employers must protect their business and efficiency interests. The Court also acknowledged, however, in Pickering v. Board of Education (1968) that “the threat of dismissal from public employment . . . is a potent means of inhibiting speech.”

In the 1960s, the Court crafted a doctrine that afforded public employees at least some degree of First Amendment protection. In 1967, in Keyishian v. Board of Regents, the Court struck down a New York loyalty oath law that had been used to dismiss academics.

The next year the Court decided Pickering v. Board of Education, establishing that public employees do not lose their free speech rights simply because they accept public employment. The Court ruled that high school officials violated the free speech rights of high school teacher Marvin Pickering when they discharged him for writing a letter to the editor critical of school board officials.

“The problem in any case is to arrive at a balance between the interests of the teacher, as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees,” Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote.

The Pickering-Connick test evaluates modern public employee jurisprudence

Much modern public employee First Amendment jurisprudence is evaluated through the lens of Pickering and the later decision of Connick v. Myers (1983). Under the so-called Pickering-Connick test, employees must pass the threshold requirement of showing that their speech touched on a matter of public concern, defined as speech “relating to any matter of political, social or other concern to the community.” Then they must show that their free speech interests outweigh the employer’s efficiency interests.

The public concern requirement has proven difficult for lower courts to apply. If an employee’s speech relates more to a personal grievance then a matter of public importance, the employee has no viable First Amendment claim.

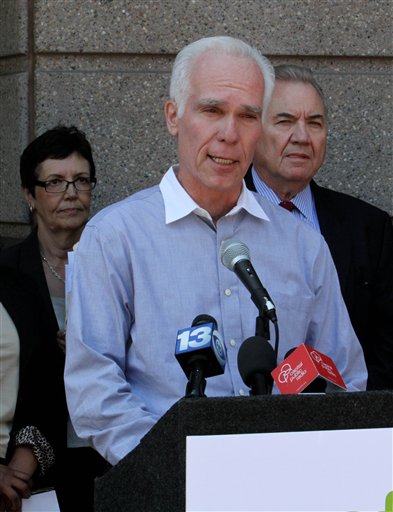

Gil Garcetti, pictured here in 2011, is the former Los Angeles District Attorney involved in Garcetti v. Ceballos, a public employee free speech case.. Ceballos was an employee in Garcetti’s office who wrote a critical memo and alleged retaliation by his employer. The court ruled that the First Amendment does not apply to speech issued as part of the routine duties of public employees. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, with permission from the Associated Press.)

Court has ruled that speech as a part of job duties has no protection

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court added a threshold requirement for public employees who assert free-speech retaliation claims. In Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006), the Court ruled that public employee speech made as part of routine job duties also has no First Amendment protection. The key inquiry is whether an employee’s speech is part of her official job duties. Many lower courts have used a “core functions” test. In other words, if the employee’s speech is part of the core functions of her job, the speech is not protected.

Many public employee lawsuits have not survived the threshold requirement of Garcetti that the employees show they were acting as citizens more than as employees performing their official job duties. Garcetti seemingly conflicts with the Court’s earlier decision in Givhan v. Western Line Consolidated School District (1979), where the Court ruled that a teacher’s complaint of racial discrimination to her principal qualified as a matter of public concern that deserved constitutional protection.

The Garcetti decision has had a palpable impact on public employee free-speech cases. Many public employees have been “Garcettized.” The U.S. Supreme Court provided protection to a public university employee who was fired after providing truthful testimony pursuant to a subpoena. “Truthful testimony under oath by a public employee outside the scope of his ordinary job duties is speech as a citizen for First Amendment purposes,” wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor for the Court in Lane v. Franks (2014).

Public employee cases are sometimes about retaliation, patronage

Public employee free speech cases sometimes take the form of retaliation cases, such as Mount Healthy City School District Board of Education v. Doyle (1977), or political patronage cases, such as Elrod v. Burns (1976). In retaliation cases, public employees must show that they suffered an adverse employment action (such as a dismissal or discharge) in retaliation for protected speech. Such employees must also show that the protected speech was a substantial or motivating factor in the employer’s decision.

In patronage cases, courts examine whether the employee in question is a “policymaking” employee in a situation where the practice of firing employees on the basis of political affiliation is acceptable. In Elrod, the Court established that the patronage practice “must further some vital government end by a means that is least restrictive of freedom of belief and association in achieving that end, and the benefit gained must outweigh the loss of constitutionally protected rights.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.