Political patronage is the appointment or hiring of a person to a government post on the basis of partisan loyalty. Elected officials at the national, state, and local levels of government use such appointments to reward the people who help them win and maintain office. This practice led to the saying, “To the victor go the spoils.” When politicians use the patronage system to fire their political opponents, those fired may charge that the practice penalizes them for exercising their First Amendment rights of political association.

Political patronage has long history in United States

Political patronage has existed since the founding of the United States. In Article 2, the Constitution delegates powers of appointment to the president; this allows the chief executive to appoint a vast number of U.S. officials, including judges, ambassadors, cabinet officers and agency heads, military officers, and other high-ranking members of government. The president’s appointment powers are checked by the Senate’s confirmation powers. This system is paralleled in many state constitutions and local charters.

Proponents of the system argued that political patronage promoted direct accountability from administrators to elected officials. They also perceived it as a means for diminishing elitism at all levels of government by allowing commoners to occupy key posts. Early presidents used patronage extensively.

As the seventh president of the United States, Democrat Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) sought to bring the government closer to the people and make it more representative. During this era of reform and “Jacksonian Democracy,” the spoils system flourished as Jackson used political patronage to reward jobs to the partisan faithful. Jackson argued that any government that aspires truly to serve the people will appoint and rotate its staff rather than create a permanent bureaucracy in which civil servants view their positions as property. This practice became the norm for several decades.

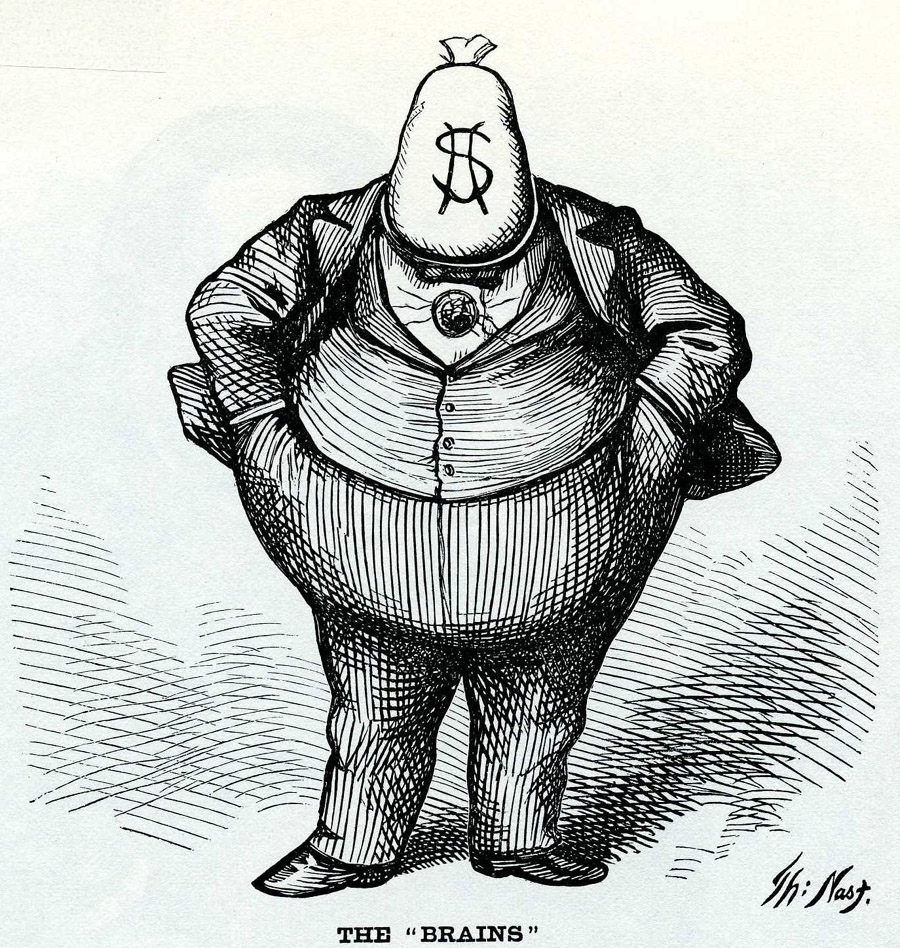

Political machines emerged in cities

The spoils system pervaded all levels of government, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was particularly evident at the local level where political machines emerged in many cities. These machines became the vehicle by which a political leader, often known as a “boss,” dominated government and politics by building a community of supporters. Tammany Hall of New York served as a prime example of such a machine.

Prominent mayors Frank Hague of Jersey City, James Michael Curley of Boston, and Richard Daley of Chicago qualified as bosses who dominated politics in their locales. While political patronage worked well in some respects, it quickly became associated with corruption. Moreover, individuals appointed to patronage positions depended on the will of those who hired them, making them unlikely to speak freely and criticize their bosses.

Government scandals associated with political patronage

Widespread government corruption, the slowing rate of immigration, and the rise of middle-class America contributed to the gradual demise of the spoils system. Late in the 19th century, concern grew that jobs were being sold and bartered to the highest bidders. Numerous government scandals and reports of inefficiency eroded public confidence.

The issue became particularly poignant when the nation’s 20th president, James A. Garfield, was shot and killed in 1881, just months after taking office, by a disgruntled job seeker. This fueled reform and led to the Pendleton Act of 1883, which shifted the appointment process to a merit-based system that emphasized recruitment through competitive exams and promotion based on competence rather than partisan identification.

Initially, only 10% of federal employees were covered by the new system, which was overseen by the Civil Service Commission. That has changed quite dramatically over time. After the enactment of the Civil Service Reform Act, signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1978, more than 90 percent of federal employees were covered by the civil service or other type of merit-based system.

Court has upheld First Amendment limitations on political patronage

In order to further impartiality, civil service employees are covered by laws — most notably the Hatch Act of 1939 — that limit their participation in partisan politics. The Supreme Court has fairly consistently upheld limits on the political activity of government employees since its decision in Ex parte Curtis (1882).

The Supreme Court imposed First Amendment limitations on patronage in a series of decisions beginning in 1976. In Elrod v. Burns (1976), the court prohibited a newly elected Democratic sheriff from firing non–civil service Republican employees. The high court reasoned that patronage dismissals infringe on core First Amendment political expression and association rights. The court extended this rationale in Branti v. Finkel (1980) and Rutan v. Republican Party of Illinois (1990).

There has been an incremental and gradual movement toward the merit-based system. Political patronage still exists at all levels of government today but is much less prevalent than in previous eras. For example, presidents now appoint fewer than 1% of all federal positions. However, appointments continue to be an important means by which presidents reward their supporters, build strength within their respective parties, and create a working relationship with members of Congress.

This article was originally published in 2009. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University.