Harlan Fiske Stone (1872–1946), a lawyer, teacher and jurist, served as both an associate justice and chief justice on the Supreme Court where he showed sensitivity to civil liberties and First Amendment values. He is regarded by experts as one of America’s great jurists.

As U.S. Attorney General, Stone restored public faith after scandals

Born in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, Harlan Stone graduated from Amherst College in 1894 and taught physics and chemistry at Newburyport High School in Massachusetts. While attending Columbia Law School, he taught history at Adelphi Academy in Brooklyn. He so impressed his professors at Columbia that he was offered a position on the faculty after he graduated and passed the bar in 1899. He practiced law and taught until his appointment in 1911 as dean of the law school, a position he held for twelve years.

He protested against Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s Red Scare raids in 1919. In 1923, he was appointed U.S. attorney general by his Amherst classmate, President Calvin Coolidge, replacing the disgraced Harry Daugherty. Stone was instrumental in restoring public faith in the Justice Department following the Teapot Dome scandal and other scandals that had occurred during Warren G. Harding’s administration. As part of his reform of the department, Stone made J. Edgar Hoover head of the new Federal Bureau of Investigation.

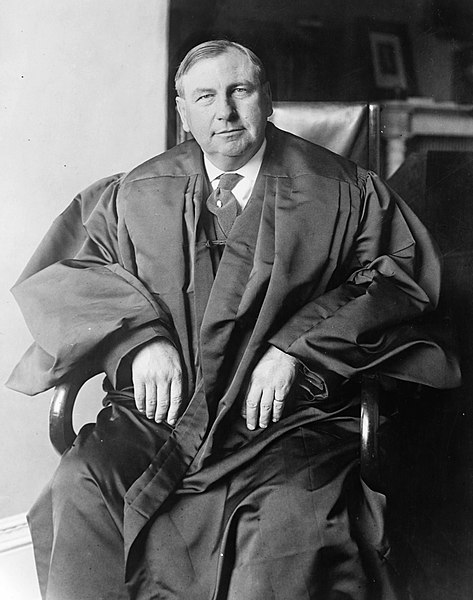

Stone became part of the liberal wing of Supreme Court

In 1925 Coolidge appointed Stone to the Supreme Court, where he allied himself with Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis to become the recognized liberal wing of the high court. A vocal advocate of judicial restraint, Stone believed that the elected representatives of the people should be given wide latitude in passing and enforcing laws and should not be hindered by a panel of appointed justices.

When Chief Justice William Howard Taft’s health began to fail in 1930, Taft suggested to President Herbert Hoover that Stone might be elevated to chief justice, though noting that he was probably too liberal and not as respectful of tradition as he should be. Stone was the odds-on bet to become chief justice, but Hoover instead appointed Charles Evans Hughes.

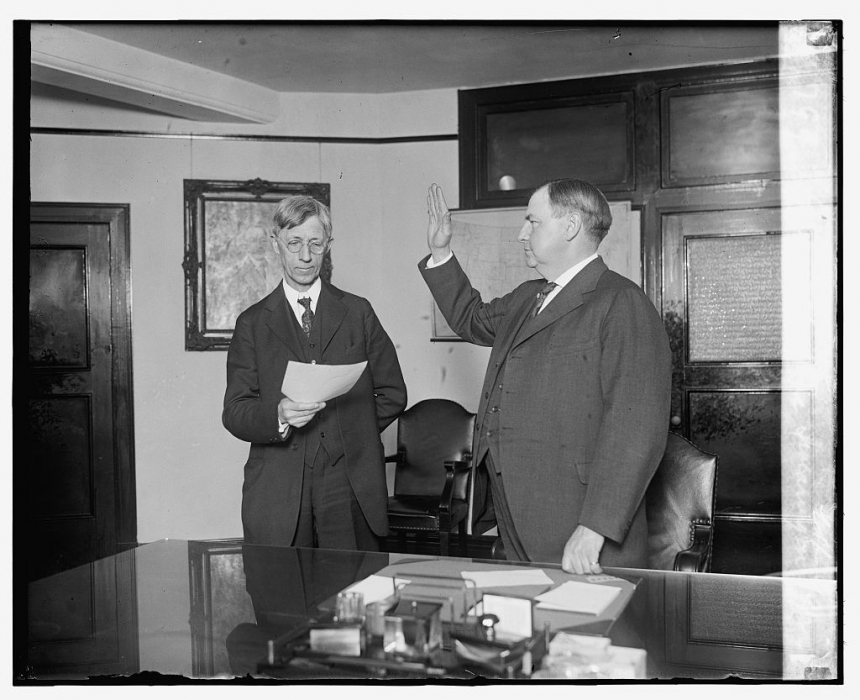

Associate Supreme Court Justice Harlan Fiske Stone swearing in, on April 9, 1924.Justice Stone, a member of the liberal Three Musketeers on the Supreme Court, forcefully supported many of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. Perhaps Stone’s most notable contribution to American constitutional law is his famous “Footnote Four” in his opinion in United States v. Carolene Products (1937). This footnote suggests that cases involving the rights of minorities at times occupy a higher plain and deserve greater scrutiny by the Court. (Image via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain)

Stone supported the New Deal

After Franklin Roosevelt’s election as president in 1932, Stone earned a reputation for writing forceful dissenting opinions in support of New Deal programs, in opposition to the “Four Horsemen” of the Court — Pierce Butler, James McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter — who most often voted with Hughes. Stone, Holmes, and Brandeis, and later Benjamin N. Cardozo, who replaced Brandeis, became known as the “Three Musketeers.”

Perhaps Stone’s most notable contribution to American constitutional law is his famous “Footnote Four” in his opinion in United States v. Carolene Products (1937), a routine due process and interstate commerce case. In acknowledging the presumptive constitutionality of Congress’s regulatory power over interstate commerce, Footnote Four suggests that cases involving the rights of insular and discrete minorities occupy a higher plane and deserve greater scrutiny by the court when laws affecting those minorities appear on their face to be unconstitutional or when they distort the democratic process to discriminate, especially when the victims lack the power and influence necessary to seek redress in the political arena. This footnote also suggested that the court should extend special scrutiny to laws that seemed to violate specific provisions of the Bill of Rights either directly or as applied to the states through the 14th Amendment. This greater scrutiny became referred to as “strict scrutiny” in later decisions.

In Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), Stone clearly and vigorously stated that First Amendment protections extended to the states by way of due process clause in the 14th Amendment. In this, he was echoing the opinions of Harlan and Brandeis before him.

In 1941, Harlan Stone was appointed chief justice in 1941. West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), a case that invalidated a compulsory flag salute law in public schools and said public school students had some First Amendment rights, was the high point of the Stone court (Image via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain)

As chief justice, Stone showed interest in individual civil liberties

After Hughes resigned in 1941, Roosevelt rewarded Stone for his support of New Deal programs by appointing him chief justice (although Stone had actively opposed Roosevelt’s “Court-packing plan” of 1937). Roosevelt’s action was an attempt to promote national unity and also a nod of amity toward the Republicans as the war in Europe became more ominous.

As chief justice, Stone fell short of what was expected of him. In spite of his devotion to the goal of civil liberties of minorities, he voted with the majority in Korematsu v. United States (1944) and wrote the opinion in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), both cases upholding the arrest and conviction of Japanese Americans for curfew violations in the early days of World War II.

Flag salute laws in schools invalidated under Stone court

Stone was the lone dissenter in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), which upheld a flag salute law challenged by Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Three years later he would preside over the Supreme Court in overturning that decision in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). In invalidating a compulsory flag salute law in schools, Justice Robert H. Jackson drew heavily from Stone’s dissent in Minersville in his majority opinion in Barnette. Jackson went further than Stone, stating eloquently that if there is a fixed star in our constitutional heaven it is that “no official, high or petty” can declare what is orthodox in politics, nationalism, or religion. Stone was appreciative of the tribute that Jackson extended.

The Barnette case was the high point of the Stone court. As chief justice, Stone lacked the authority necessary to manage the increasing clash of personalities, especially among Hugo L. Black, Felix Frankfurter, and William O. Douglas. On one occasion he was roundly criticized by Frankfurter and Owen J. Roberts in a dissent in a minor case for the Stone Court’s tendency to refer to the “unwisdom and injustice” of earlier decisions in what they perceived as Stone’s penchant for overturning precedent. Frankfurter, in particular, was distressed by what he perceived as Stone’s unruly court.

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone at his desk in 1924. After being appointed chief justice in 1941, Stone had a hard time controlling the domineering personalities on the Supreme Court. (Image via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain)

Clearly, Stone had been much happier as a member of the team than he was as its leader. He lacked the administrative skills of Taft and the discipline of Hughes. He was reluctant to rein in the increasingly hostile factions on the high court.

On April 22, 1946, as Stone was about to read three decisions of the court, he appeared to collapse. The court quickly adjourned to an anteroom. The chief justice died that evening.

Stone, a Republican, was a man of honor, integrity, and humility who transcended political boundaries. He was a standout teacher, a loyal citizen, and a devoted husband and father. He believed in judicial restraint, he respected the supremacy of the elected representatives of the people, and he had a profound interest in the civil rights of minorities. He tried to uphold these principles, with few exceptions, in a fair and consistent manner. His Footnote Four reshaped the Supreme Court’s agenda of the future, moving the content of the docket from a predominance of business–government relations cases to an agenda dominated by civil and individual liberties cases.

This article was originally published in 2009. James R. Belpedio was a professor of history at Becker College.