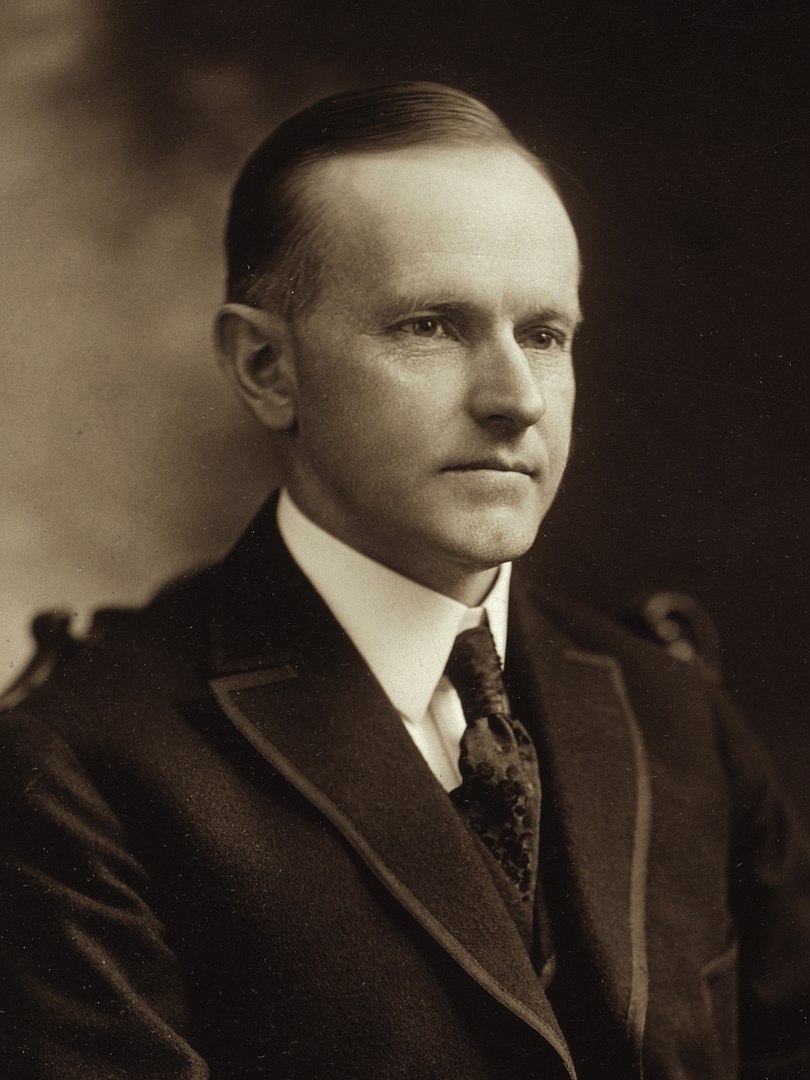

Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) was born on July 4, 1872, in Plymouth Notch, Vermont, where he would receive the news in 1923 that President Warren G. Harding, under whom he served as vice president, had died and that he was now president. His father, a justice of the peace, had administered the oath to him by the light of a kerosene lamp.

Coolidge was overwhelmingly reelected in 1924 (an event saddened by the death of one of his sons) and served until 1929, when Herbert Hoover succeeded him.

Coolidge earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst University and was apprenticed to a lawyer before setting up his own law practice. He successively served as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, as the mayor of Northampton, as a member of the Massachusetts Senate, as lieutenant governor and as governor. As governor, he became best known for sending in the National Guard and breaking a policeman’s labor union strike in Boston in 1919 during the first Red Scare period when many Americans were fearful of a communist takeover.

Although President Harding made some wise appointments, including former president William Howard Taft as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, he also relied on cronies who used their positions for financial gain. This resulted in congressional investigations, particularly of the so-called Teapot Dome Scandal involving administration officials who accepted bribes for the noncompetitive leasing of federal lands to oil companies.

By contrast, the taciturn Coolidge brought an aura of integrity and dignity back to the Oval Office. Like Harding, he believed in a minimalist national government. Although some believe his lax oversight of the economy contributed to the Great Depression that began in 1929, he left office as a very popular and well-respected man. He was succeeded by Herbert Hoover who had served as his Secretary of Commerce.

Supreme Court upholds convictions of Communists during Coolidge’s presidency

Although Coolidge was not nearly as gregarious as his predecessor, he was a good public speaker. He was the first of many presidents who attended the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

Throughout Coolidge’s administration, William Howard Taft remained chief justice. Congress significantly increased the power of the high court and its ability to focus on civil liberties when in the Judiciary Act of 1925, better known as the Judges’ Act, it granted the Supreme Court the power to determine which cases it would hear through writs of certiorari.

During Coolidge’s presidency, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex Parte Grossman (1925) that a president could pardon an individual for criminal contempt of court. In Myers v. United States (1926), it further ruled that a president could fire executive officials without senatorial consent.

The first Red Scare (1917 to 1921) had raised fears of communists and radicals that persisted into the succeeding Republican nominations. Early in Coolidge’s presidency, Congress adopted the 1924 Immigration Act that discriminated against southern and eastern European immigrants. In Whitney v. California (1927), the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a member of the Communist Labor Party for violating the California Criminal Syndicalism Act of 1919. In 1928, the high court upheld the conviction of a member of the Ku Klux Klan who had violated a state law requiring that he register as a member.

In rejecting a plea to give amnesty to individuals who had been convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917, Coolidge said that “no man should be held in prison because of opinions he had expressed” but added that freedom of speech should not “extend to those who during the war attempted to stir up a general public opinion hostile to the purposes of the Government.”

In 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, extending citizenship to Native Americans who had not been covered by the adoption of the 14th Amendment.

Conflicts arise over religion in schools, teaching evolution

The famous Scopes Monkey Trial occurred in Dayton, Tennessee, during Coolidge’s presidency. The conviction of a high school teacher for teaching evolution in a public school in Tennessee, although later overturned by a technicality, highlighted the conflict between fundamentalists and modernists. Perhaps wisely, Coolidge did not comment on this case.

In Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), the Supreme Court affirmed the right of parents to send their children to parochial schools. Although Coolidge had initially expressed some support for an Equal Rights Amendment, he ended up instead sponsoring protective legislation for both women and children (Walker 2012, 64).

In 1925, Coolidge addressed the Annual Council of the Congregational Churches in Washington, D.C. Much like some of the early presidents, Coolidge stressed the importance that citizens’ religious convictions for maintaining law and order while upholding separation of church and state. He noted that:

“[O]ur institutions have undertaken to recognize that the human mind is and must be free. This is one of the reasons why it is neither practical nor justifiable to impose upon the Government the responsibility for the ultimate provision of the instrumentalities which minister to the spiritual life.”

Coolidge argued, however, that the foundational principles of American government, as articulated in Founding documents, “have no foundation other than the common brotherhood of man derived from the common fatherhood of God.” He further said that “I do not know of any adequate support for our form of government except that which comes from religion.”

Court extends speech, press freedoms of First Amendment to states

The most consequential decision relating to the First Amendment during the Coolidge Administration arguably occurred in 1925 when the Court declared in Gitlow v. New York that it considered the guarantees of freedom of speech and press in the First Amendment to apply to the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. This development continued until all the provisions of this amendment and almost all of the provisions of the Bill of Rights now apply to both state and national governments.

Coolidge’s State of the Union Address in 1925 was the first to be transmitted by radio. A further sign of the changing technology surrounding the First Amendment was the adoption of the Radio Act of 1927, which Coolidge signed during his presidency. It refined rules for radio licensing and ordered stations to provide for the expression of rival views.

In 1926, Coolidge was president during the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In a speech on July 5, Coolidge characterized the Declaration as “a great spiritual document.” He noted that the nation had been founded on the principles of the equality of men, on their possession of inalienable rights and on their right to self-government. Tracing such ideals back to early colonists, Coolidge observed that “(i)n order that they might have freedom to express these thoughts and opportunity to put them into action, whole congregations with their pastors had migrated to the Colonies.”

Coolidge appoints Harlan Fiske Stone to Supreme Court

Coolidge’s only appointment to the Supreme Court was Harlan Fiske Stone, who, as his attorney general, had cleaned up the Department of Justice and whom Franklin D. Roosevelt elevated to the chief justice in 1941. Stone authored the famous Footnote Four in United States v. Carolene Products (1938) in which he suggested that the court should give greater scrutiny to provisions in the First Amendment and the Bill of Rights than to economic regulations.

Coolidge also appointed J. Edgar Hoover as head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which he directed until 1972, often without close regard for individual rights.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 29, 2023.