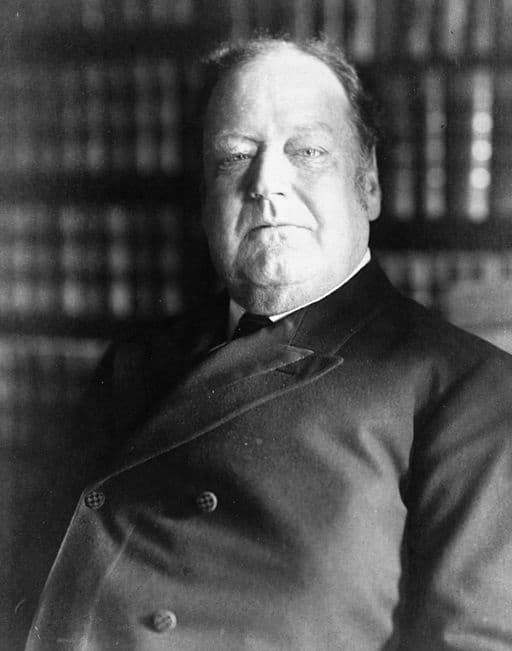

Edward Douglass White (1845-1921), the ninth chief justice for the Supreme Court, was born in Louisiana where his father had served as a state governor. His father died when White was only three years old.

White became a lawyer, fought during the Civil War for the Confederacy, and was captured by Union forces. He subsequently served in the Louisiana Senate, on the state Supreme Court, and as a U.S. senator.

Grover Cleveland named White to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1894. He served as an associate justice from 1894 to 1910 and was elevated by President William Howard Taft to the chief justiceship when Melville Fuller died in 1911. White served until his own death in 1921.

Although White is regarded as a competent chief, he is not known for having the same philosophical distinctiveness as some other justices who have held this post.

White joined decisions restrictive of speech involving Sedition Act

Congress adopted the Sedition Act of 1918 during World War I, which resulted in a number of First Amendment cases reaching the Supreme Court.

In 1897, White as an associate justice had delivered the court’s speech-restrictive decision in Davis v. Massachusetts, where he ruled, in a precedent that has since been overturned, that municipalities had control over open-air speech.

In similar fashion, almost all the cases that derived from World War I and the sedition and espionage acts, all of which White joined, were restrictive toward speech.

He joined the unanimous decision written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in Debs v. United States (1919), upholding the conviction of pacifist labor leader Eugene Debs under the Sedition Act for his opposition to World War I. That same day in Frohwerk v. United States (1917), the court upheld another conviction of an individual for criticizing U.S. participation in World War I under the Espionage Act of 1917.

In Abrams v. United States, White also joined the court in an opinion written by Justice John Clarke upheld the sentencing individuals for violating the 1917 Espionage Act for distributing leaflets condemning U.S. intervention in Russia.

In Schenck v. United States (1919), the court again upheld convictions under the Espionage Act of 1917 for obstructing the recruiting and enlistment programs for the war. It was in this case that Justice Holmes introduced the clear and present danger test.

It was not until after White’s death and the court’s decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that the court would begin incorporating provisions of the First Amendment into the 14th Amendment so that they also protected citizen rights against state action.

White's most important decisions involved Standard Oil

White also participated in some of the court’s most notable cases during his tenure.

As an associate justice, White had concurred in Justice Henry Bills Brown’s majority decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upholding the doctrine of separate but equal in regard to racial separation.

One of White’s most important decisions as chief was his decision in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. U.S. (1911) when he ruled that the Sherman Anti-Trust Act should be subject to a “rule of reason” that only prohibited “unreasonable” restraints of trade.

White also joined the majority in the case of Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), when the court decided (in a precedent that has since been overturned) that Congress did not have authority under the interstate commerce clause to ban child labor.

Other important cases included the Insular Cases in which the court ruled that only some protections of the Bill of Rights applied within U.S. territories.

When White died, Warren G. Harding appointed former president William Howard Taft as his replacement.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.