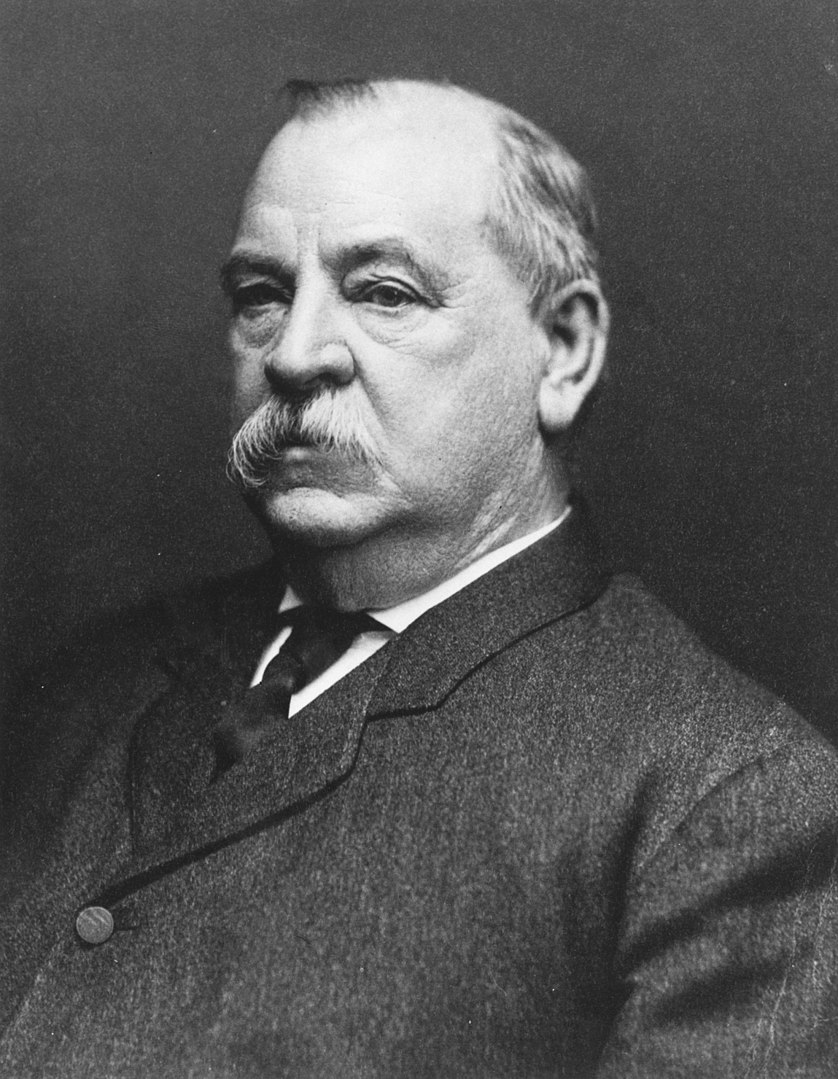

Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) has the distinction of being the only U.S. president to serve two non-successive terms. He became the 22nd president when he served from 1885 to 1889 and the 24th when he served from 1893 to 1897.

Born in New Jersey (his father was a Presbyterian minister) and largely raised in New York, he taught briefly before reading law with a lawyer in Buffalo, New York, and being admitted to the bar.

He was appointed as assistant district attorney of Erie County, New York, and, as the law permitted, paid a recent immigrant to serve in his place in the Union Army. As a lawyer, Cleveland earned a reputation for conviviality, hard work and absolute integrity. He served as both mayor of Buffalo and as governor of New York before winning the presidency as the Democrat nominee against Republican James G. Blaine in 1884. He lost the electoral college (albeit not the popular vote) to Benjamin Harrison in 1888 but defeated him in the election of 1892.

Cleveland was thus the only Democrat to serve as president between the presidency of James Buchanan and Woodrow Wilson. Noted for his speaking ability, Cleveland gave his inaugural addresses from memory.

Grover Cleveland’s political stances

Cleveland was a proponent of a strong gold-based monetary system and an opponent of high protective tariffs. He also pushed back against the Tenure of Office Act of 1867, now considered to be unconstitutional, which had provided that the president could not fire certain appointees without senatorial consent. He was a fiscal conservative who vetoed more bills during his two terms than any president other than Franklin D. Roosevelt. In one of his most famous vetoes, Cleveland voided a bill to provide seeds for an area of Texas that had been struck by drought. Believing that this was a local matter, Cleveland said, in words that seem very foreign today, that “though the people support the Government the Government should not support the people.”

Cleveland was president at a time when the Supreme Court had not yet applied the provisions of the First Amendment to the states, so judicial activity on the subject during his administrations was limited.

Religious intolerance intruded into his first presidential campaign but probably tipped the balance on Cleveland’s behalf when the Rev. Samuel D. Burchard stirred emotions among Catholic voters by charging that the Democratic Party was the party of “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” (See "'Rum, Romanism and Rebellion' Resurrected" by David G. Farrelly, 1966, p. 262). Cleveland was also accused of having father an illegitimate child, a possibility that he did not deny.”

At a time when Cleveland and others were calling for free universal education, James G. Blaine, the Republican House minority leader and Cleveland’s 1884 electoral opponent, had unsuccessfully proposed a constitutional amendment applying the establishment clause to the states and prohibiting any governmental funds from going to parochial schools. Numerous states subsequently adopted their own “Blaine amendments” to make sure religious schools would not be funded by government.

First Amendment issues

Cleveland was a bachelor until he was married at the age of 49 in a ceremony in the White House in 1886. Journalistic snooping into his honeymoon led him to give a speech at Harvard University decrying what he described as the “silly, mean, and cowardly lies that every day are found in the columns of certain newspapers which violate every instinct of American manliness, and in ghoulish glee desecrate every sacred relation of private life.”

After the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a law repealing the charter of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and confiscating its property for educational purposes in Late Corporation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. v. United States (1890), the church renounced polygamy. The government returned its property, and Cleveland pardoned those who promised to obey state marital laws against polygamy.

Cleveland stops union boycott, protests at Capitol

In his second term, Cleveland invoked the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to obtain an injunction against a secondary boycott by the American Railway Union. The union was boycotting enterprises owned by the Pullman Palace Car (Railroad) Company, which had reduced wages without a corresponding reduction in rents and other charges in its company town where most Pullman workers lived.

The court granted the injunction. After the railway’s union leader Eugene Debs and others continued the boycott anyway and were convicted of contempt of court, the Supreme Court in In re Debs (1895) upheld the convictions.. Later, during World War I, Debs would be imprisoned for violating the Espionage Act for a speech he gave in Canton, Ohio, that the government said incited insubordination, disloyalty and refusal to serve in the military.

In 1894, Cleveland also dealt harshly with Coxey’s Army, a group that marched on the U.S. capital under the direction of Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey seeking government support for hiring the unemployed for public infrastructure works (See “The Criminalization of Free Speech: A Through Line from 1894 to the Present” by Jeff Miller, ACLU of Ohio, April 28, 2021). When Coxey and other movement leaders walked onto the grass at the Capitol, they were arrested. The march was notable as the first protest march on Washington, D.C.

In other actions, in 1888, Cleveland signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which introduced a race-based distinction into U.S. immigration laws. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that approved racial segregation. In its decision in Hennington v. Georgia (1896), the court upheld a Georgia law forbidding trains from running on Sunday, using reasoning that it would used in the next century to uphold the legitimacy of Sunday closing laws against challenges that such laws violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Cleveland appoints four justices to Supreme Court

As president, Cleveland had the opportunity to appoint four justices to the Supreme Court. They were Lucius Lamar, Melville Fuller (as chief justice), Edward Douglass White (whom William Howard Taft would later elevate to the chief justiceship) and Rufus W. Peckham. Cleveland also appointed the conservative legal scholar Thomas Cooley, a strong defender of First Amendment rights, to chair the Federal Trade Commission.

Cleveland was succeeded in office by William McKinley who continued the gold standard but during whose administration the U.S. acquired foreign colonies, which Cleveland had opposed.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 20, 2023.