Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1952), remains the central precedent for the constitutionality of state group libel laws, but the decision by the Supreme Court was so divided (5-4) and the subsequent precedents so powerful that the decision may retain little if any force.

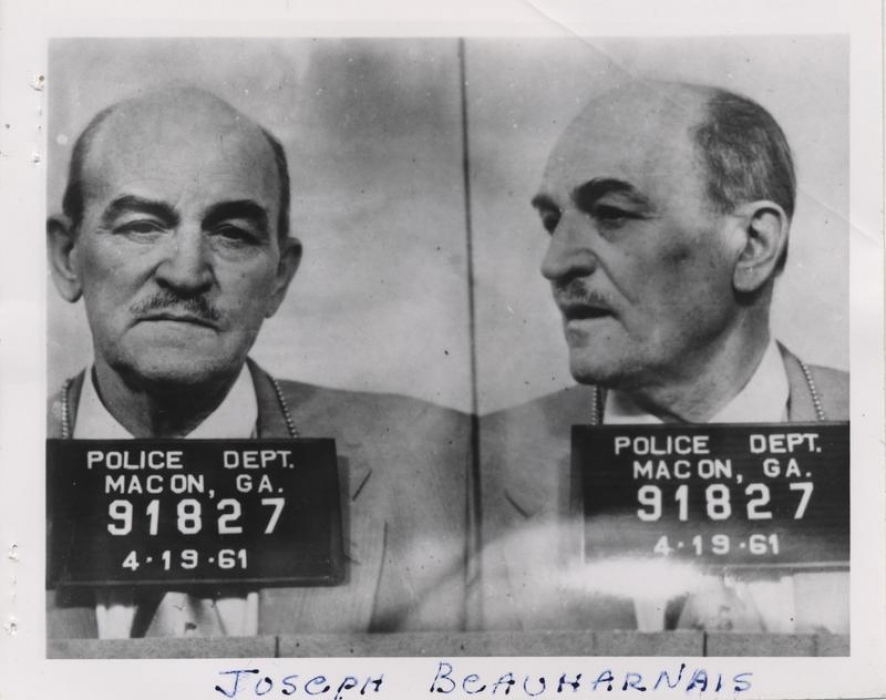

Beauharnais convicted of group libel

The Municipal Court of Chicago convicted Joseph Beauharnais, president of the White Circle League of America, of group libel under a state law designed to prevent breach of the peace. Beauharnais had been circulating a pamphlet alleging that African-Americans were associated with “aggressions … rapes, robberies, knives, guns and marijuana” [ellipses in the original].

The judge, who had ordered the jury to convict if it found that Beauharnais had distributed the pamphlet, had refused to give the defendant an opportunity to prove the truth of his assertions.

Court upheld the conviction; said states could experiment with group libel laws

Writing for the majority, Justice Felix Frankfurter upheld the conviction. His review of U.S. libel laws revealed that criminal libel prosecutions had been permitted in the past, and he pointed to race riots and other acts in Illinois related to racial hatred to indicate that such libel of groups could lead to breaches of the peace.

According to Frankfurter, states had the right under the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment (which he found had not “incorporated” all the provisions of the Bill of Rights) to experiment with laws that might tamp down such violence by restricting the publications that fed them. He clarified, however, that the decision was not based on the “wisdom” or “efficacy” of the legislation.

Black said states should not be able to ‘experiment’ with ‘seditious libel’

Justice Hugo L. Black wrote a dissent in which Justice William O. Douglas concurred. Black associated the pamphlets in question with the right to petition representatives, which he traced back to the First Continental Congress.

He argued that the decision degraded “First Amendment freedoms to the ‘rational basis’ level” and that states should not have the right to “experiment” in this area. Although labeling the statute as a “group libel law” might “make the Court’s holding more palatable … the sugar-coating does not make the censorship less deadly,” he wrote.

Black opposed the law as a form of “seditious libel” that Britain had conclusively rejected in 1792 when it adopted Fox’s Libel Law. Such “state censorship,” he asserted, was “at war with the kind of free government envisioned by those who forced adoption of our Bill of Rights.”

In affirming his absolutist approach to the First Amendment, Black said he could not “agree that the Constitution leaves freedom of petition, assembly, speech, press or worship at the mercy of a case-by-case, day-by-day majority of this Court.” Indeed, he argued, “the First Amendment, with the Fourteenth, ‘absolutely’ forbids such laws without any ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’ or ‘whereases.’ ”

Reed found case violated due process

Justice Stanley F. Reed authored a dissent as well, also joined by Douglas. He found that the procedures in the case violated substantive due process. It was not proper for the judge to refuse to allow truth as a defense, and it was not possible to determine which of the vague words in the statute had provided the basis for the conviction. “It is when speech becomes an incitement to crime that the right freely to exhort may be abridged,” Reed wrote. He could find no link between the publication at issue and the racial clashes that Frankfurter had described in his opinion.

In his own dissent, Justice Douglas acknowledged that states could suppress a conspiracy, such as that carried out by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, when it involved “free speech plus,” but prohibitions against regulating speech itself was “couched in absolute terms” for a reason. “Debate and argument … are not always calm and dispassionate. Emotions sway speakers and audiences alike. Intemperate speech is a distinctive characteristic of man. Hotheads blow off and release destructive energy in the process.” The decision thus represented “a philosophy at war with the First Amendment.”

In his dissent, Justice Robert H. Jackson agreed with Frankfurter that the 14th Amendment did not “incorporate” the provisions of the First Amendment. However, he observed that the “Court has never sustained a federal criminal libel Act,” and he affirmed the decision in United States v. Press Publishing Co. (1911), in which the Court refused to do so.

Scope of decision has been limited

The scope of this decision has been limited by later Supreme Court decisions relative to hate speech, such as Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992).

Moreover, the Court’s recent decision in Matal v. Tam (2017), which prohibited the Patent and Trademark Office from denying trademarks (in this case, to a rock group calling itself “The Slants,”) that it considered to be disparaging to racial groups, might further indicate a reluctance to censor speech in this area.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.