The term “hate speech” is generally agreed to mean abusive language specifically attacking a person or persons because of their race, color, religion, ethnic group, gender, or sexual orientation. Although the First Amendment still protects much hate speech, there has been substantial debate on the subject in the past two decades among lawmakers, jurists, and legal scholars.

Debate over hate speech flared over campus speech codes

The scholarly debate concerning the regulation of hate speech flared in the late 1980s, primarily focusing on campus speech codes, pitting those who view regulation of hate speech as a necessary step toward social equality against those who see hate speech regulations as abridgements of the fundamental right of free speech.

Liberal theorists say more speech is the First Amendment remedy for hate speech

The traditional liberal position is that speech must be valued as one of the most important elements of a democratic society. Traditional scholars see speech as a fundamental tool for self-realization and social growth and believe that the remedy for troublesome speech is more speech, not more government regulation of speech. For example, liberal theorist Nadine Strossen, relying to some degree on John Stuart Mill’s connection between speech and the search for truth, argues that restricting hate speech will mask hatred among groups rather than dissipate it.

Balance between free speech and social equality a concern

Proponents of hate speech regulation usually do so from the perspective of critical race theory, believing that legal decisions are based on preserving the interests of the powerful, and see no value in protecting bias-motivated speech against certain already oppressed groups. They question the necessity and logic of protecting speech that not only has no social value but is also socially and psychologically damaging to minority groups. These proponents of the regulation of hate speech suggest a new balance between free speech and social equality.

For example, Mari Matsuda, a law professor at Georgetown University, has advocated creating a legal doctrine defining proscribable hate speech from a basis in cases where the message is one of racial inferiority, the message is directed against a historically oppressed group, and the message tends to persecute or is otherwise hateful and degrading.

The Illinois Supreme Court reviewed the question of restricting a Nazi rally in Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America (1978). The court, relying heavily on a U.S. Supreme Court case, Cohen v. California (1971), raised the slippery slope argument, contending that restricting the wearing of a swastika would lead to an endless number of restrictions on all sorts of offensive speech. Adhering to the content neutrality principle, the court ruled that the government could not base rules on the feelings of “the most squeamish among us” and that the wearing of swastikas was “a matter of taste and style.”

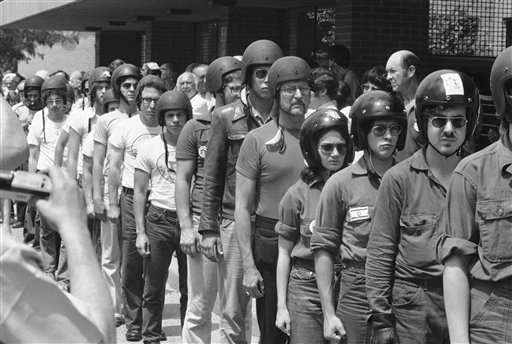

Members of the Jewish Defense League donned helmets as they arrived in Skokie, north of Chicago on Monday, July 4, 1977. They were one of the groups demonstrating against a march of the National Socialist Party (Nazis), who called off a Fourth of July march when they failed to get a permit. The Supreme Court contended that restricting the wearing of a swastika would lead to an endless number of restrictions on all sorts of offensive speech. Adhering to the content neutrality principle, the Court ruled that the government could not base rules on the feelings of “the most squeamish among us” and that the wearing of swastikas was “a matter of taste and style.” (AP Photo/CEK, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

Court struck down hate speech law

In R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992) the Supreme Court appeared to close the door on hate speech regulations. The case involved a city ordinance in St. Paul, Minnesota, prohibiting bias-motivated disorderly conduct against others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, or gender. The Court struck down the ordinance, finding it to be unconstitutional on its face because it was viewpoint discriminatory.

The Court reviewed whether hate speech as defined in the ordinance fit into the “fighting words” category. This category, first established in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), was defined as “such words, as ordinary men know, are likely to cause a fight.” The Court in R.A.V. found that the ordinance had removed specific hateful speech from the category of fighting words because, by specifying the exact types of speech to be prohibited, the restriction was no longer content neutral.

Court upheld cross-burning law

More than a decade later, the Supreme Court again ruled on a hate speech case. Virginia v. Black (2003) concerned the constitutionality of a Virginia statute that made it unlawful to burn a cross with the intent of intimidating any person or group of persons. Many scholars have argued that the Court’s opinion in Black is completely opposite from its ruling in R.A.V.

Relying on the history of the use of cross burnings to intimidate African Americans, the plurality found that R.A.V. did not mean “the First Amendment prohibits all forms of content-based discrimination within a proscribable area of speech.” The Court did accept the idea that some individuals might burn crosses for reasons other than intimidation.

Hate speech law has now focused on the Internet

Current case law and research concerning hate speech has shifted focus toward hate speech on the Internet. The Internet brings with it a myriad of new problems for the First Amendment, including how to determine what level of scrutiny to apply and how to react to existing restrictions on hate speech by much of the international community.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Chris Demaske is an associate professor of communication at the University of Washington Tacoma. Her research explores issues of power associated with free speech and free press and has covered topics including hate speech, academic freedom, and Internet pornography.