Since the early 20th century, the concept of group libel has coexisted uneasily with the First Amendment’s overarching emphasis on individual speech rights. The idea that it is socially desirable to minimize defamation of an entire group of people has effectively taken a back seat to the preservation of the individual right of self expression.

The American law of libel is rooted in English common law, particularly its ban on seditious libel. In England, criticism of the monarch and the monarch’s government was a crime, as was speech (oral or published) whose purpose was to foment discontent and discord among the people. By stamping out defamation of particular groups, the government could simultaneously maintain order and uphold political loyalties.

The American Revolution conferred a new sense of legitimacy on political protest and engendered a broader tolerance for libelous speech. Prosecutions of criminal libel dropped off considerably after independence, and President John Adams’s reinvigoration of seditious libel in the Sedition Act of 1798 confined him to one term.

Winning group libel lawsuit requires showing individuals were harmed

Throughout the 19th century, the smaller or narrower the subject of the defamation, the easier it was for individuals to win civil libel cases. Still, there were significant obstacles to winning such suits. Members of a defamed group were generally denied standing to sue on behalf of the group, and members of racial or religious groups almost never succeeded in establishing their right to sue. The law of individual libel required that the defamer had caused pecuniary damage to individuals, making it difficult for anyone to prove that language that defamed a group also caused legally recognizable harm to an individual.

The most important factor in changing the legal landscape of group libel was the sharp rise in Jewish immigration to the United States between 1880 and 1920. Jews were denied welcome at hotels, resorts, public accommodations, and schools. Exacerbating that insult, resort owners began openly advertising their policies in order to attract elite guests.

Seven states adopt laws prohibiting discriminatory language in advertisements

In 1907 a hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey, declined accommodations to a prominent American Jewish woman. She complained to Louis Marshall, a lawyer and president of the American Jewish Committee. Marshall drafted a law that barred the printed advertising of discrimination in public accommodations on the basis of race, color, or creed. Enacted in 1913, this statute did not require hoteliers to rent rooms to all comers but prohibited the publication and dissemination of statements that advocated discriminatory exclusion. By 1930 seven states had adopted versions of the New York statute, making group rights a nascent category in First Amendment law. Throughout the 1930s the laws remained untested in the courts. Marshall apparently preferred to field inquiries from resort owners about the legalities of their advertisements than to file lawsuits.

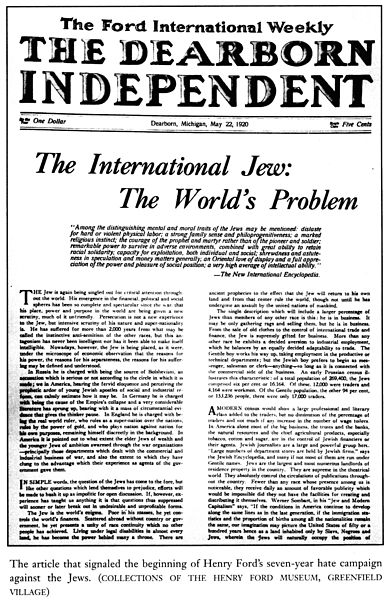

A famous libel lawsuit brought by Aaron Sapiro, a lawyer, against Henry Ford in 1927 over anti-Semitic articles in Ford’s Dearborn Independent and a book entitled The International Jew demonstrated that group libel remained an ineffective basis for damage claims. Still, Ford’s apology to “Jews everywhere” implicitly recognized the symbolic power of group libel.

After World War II and the Holocaust, American courts showed some willingness to tolerate restrictions on speech.

Supreme Court upholds conviction under Illinois group libel law

In Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952), the Supreme Court upheld the conviction, under an Illinois group libel statute, of an individual who circulated a petition protesting the incursion of blacks into white neighborhoods. The Court has treated that precedent with tepid enthusiasm ever since, giving speech expressing racial hatred essentially the same protection as “other speech that causes ordinary offense or anger.”

No broad conception of group rights emerged in libel cases against newspapers (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan [1964]); cases striking down municipal hate speech regulations (R.A.V. v. St. Paul [1992]); or cases challenging campus hate speech codes.

A notable exception occurred in Virginia v. Black (2003), when the Court held that cross burnings done with the intent to intimidate were not protected speech because they are universally understood as an attack upon an entire race. Nevertheless, group libel remains a fringe category in U.S. law.

This article was originally published in 2009. Victoria Saker Woeste is a historian specializing in U.S. legal and constitutional history and the author of several books and articles relating to First Amendment issues including Henry Ford’s War on Jews and the Legal Battle Against Hate Speech (Stanford University Press, 2012).